|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > Blogs > Cheshire Cat Blog > 2011 |

|

|

back |

The Cheshire Cat Blog

|

|

May 2011 |

|

| |

|

|

|

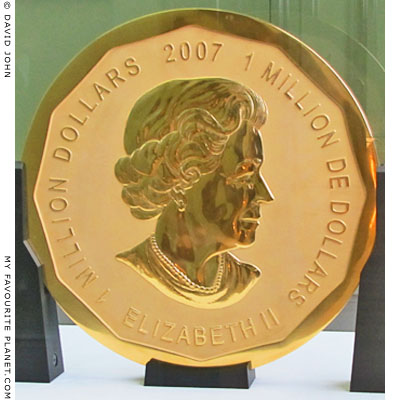

| The world's largest coin is on show at Berlin's Bode Museum. The gold Canadian one million dollar coin, with the head of Queen Elizabeth II on one side and maple leaves on the other, is 53 cm in diameter, 3 cm thick and weighs 100 kg. But will it fit in your pocket or buy you a cup of coffee in the museum's café? We all know the Cat can look at the Queen, and so The Cheshire Cat slinked along to sneak a peek. |

|

| |

The reverse side of a one million dollar Canadian "Big Maple Leaf" gold coin

at the Boden Museum, Berlin, Germany. |

| |

The obverse side of the coin depicts Queen Elizabeth II, Canada's head of state. The portrait of Her Majesty (a very nice girl, apparently) was made by the Canadian artist Susan Blunt. The reverse side shows three wind-blown maple leaves by engraver Stan Witten. The maple leaf is the emblem of Canada, and the country's gold coins are known as "maple leaves". This one, for obvious reasons, is known as "the Big Maple Leaf". The twelve-sided, recessed face of each side has been rendered a creamy-coloured matt to highlight the polished gold of the lettering, images and the rim of the coin. |

|

O Canada! |

The reverse side is marked "SW" for Stan Witten, "Canada", "fine gold 100 kg or pur" (in English and French) and "99999" (twice for the sake of symmetry, or is the second 99999 in French?), which refers to the fact that 99,999 grams of the coin's 100,000 grams weight, i.e. 99.999%, is pure gold. What the remaining gram consists of is not stated, but it is claimed that this is the highest standard of gold purity ever attained for coinage. Previously a mere 99.99% had been used for "maple leaves" since 1982.

While the faces of coins are normally stamped onto metal blanks, the size of this monster coin meant it had to be created in a special mould which kept the entire mass of liquid gold at a uniform temperature during the pouring.

You may ask, quite justifiably, what is the point of a coin which you can't carry around and are very unlikely to get change from, even at Harrod's? Apparently the Canadian Royal Mint in Ottowa planned the coin as a one-off show-piece in 2007. However, the idea attracted so much interest that the Mint decided to produce 5 of them - a very limited edition indeed. One was retained by the Mint and the other four were bought by private investors. Strangely, the value of the gold used to make the coin is far greater than its face value of 1 million Canadian Dollars. In June 2010 this particular coin was sold at auction at the current gold price of 3.2 million Euros (then worth around 4 million Dollars).

On 18 October 2007 the Guinness World Book of Records recognized the edition as the largest coin in the world. This in itself is bound to help make the exhibit a popular draw at the recently renovated Bode Museum (see below) on Berlin's Museumsinsel (Museum Island) on the River Spree. |

|

|

Although the piece is admirable for its enticing glitter and as a product of its makers' supreme engineering, metallurgical and technological skills, standing in front of the coin, literally face-to-face, unfortunately evinces a "so what?" effect. Since it is far too valuable to touch, displayed as it is in a high-security glass case (although at 100 kg nobody is likely to attempt to run off with it), and much too large and heavy to hold in the hand, as a coin it doesn't work and as an object it is too bland in design to astound. It looks just like a giant, overblown mock-up of a smaller coin, without the charm or fascination evoked by the visual and haptic effect of finely detailed metalwork. It may just as well be made of papier mâché and paint, or chocolate wrapped in golden paper. For this price, one would expect something of a much higher order of creative detailing and use of the disc's generous space - on all three sides. Lovely leaves, though, Stan.

A CBC news article reporting the release of this coin was headlined, somewhat ironically: "Finally! A 100-kg Canadian gold coin" [1]. Essentially, it can only be of real fascination to numismatologists, investors and people who like huge, shiny, expensive things which they are never likely to get their hands on.

Happily, in the neighbouring rooms of the Bode Museum are displayed many much finer coins, medals and other objects which are witnesses to human ingenuity, skill and creativity dating back to ancient ages. |

|

One of the Bode

Museum's oldest

and smallest coins,

a Persian gold daric,

5th-4th century BC. |

|

"Gold Giganten - the biggest gold coin in the world" is on show at the Bode Museum,

Berlin, Germany until 31 July 2011. Please form an orderly queue. |

|

| |

Small change

A few of the Bode Museum's collection of ancient coins.

All the photos in this section show the coins at approximately the same scale. |

|

|

| |

| |

Persian gold daric,

Persian gold daric,

5th - 4th century BC. |

Despite the Canadian Royal Mint's boast of achieving 99.999% purity in its giant gold coins - with the help of advanced modern technology - the Persians managed 99% in the 6th century BC with far less sophisticated means at their disposal. Not all Persian coins were of this purity, which declined to a shoddy 94% by the middle of the 4th century BC.

Bean-shaped Darics, weighing 8.1 - 8.5 grams, were introduced around 522-486 BC during a currency reform by Persian emperor Darius the Great (The Great King or King of Kings, 550-486 BC). The currency, which also included the gold siglos or shekel (5.4 - 5.6 grams, 1 daric = 20 sigloi), is said to have been based on Lydian coinage (see below), however the weight of the daric corresponds to the Babylonian shekel. Although it is thought that the daric (or dareikos) was named after Darius, another theory is that the name is derived from zarig, the Middle Persian word for gold.

Nicknamed "the archer" in antiquity, both the daric and the siglos depict a king as warrior, wearing a crown and carrying a bow and arrow. It is not known whether the figure was meant to be potrait of Darius or a particular emperor, or as a generic representation of imperial power.

The Persian emperors maintained a royal monopoly on coin production throughout the vast empire, and darics were in circulation until the invasion of Alexander the Great in 330 BC, after which they were melted down and recycled into coins of the new Macedonian emperor. This helps to explain their scarcity and why they are so keenly sought by coin collectors. Small amounts of darics have been found in Asia Minor, Greece, Macedonia and Italy, and sigloi have been discovered as far afield as Afghanistan and Pakistan.

| |

Pegasus on a stater

from Lampsakos

circa 390-350 BC. |

The Stater (Greek, στατήρ, "weight" or "he who weighs") is thought to have originated either in Macedonia or the Greek island of Euboea and was originally based on the Phoenician shekel. Staters were minted by several Greek states with various values from didrachm (2 drachms), tetradrachm (4 drachms) up to 28 drachm (e.g. the Kyzikenos of Cyzicus in Mysia, Anatolia).

As today with high denomination "currency", such as Canada's "Big Maple Leaf", in ancient times high value coins such as staters and dekadrachms were not minted for everyday use, nor were they to be found in street markets. Usually they were produced to pay for armies and other high value expenditures, and often for special occasions as prestige objects and as ritual donations or sacrifices.

Celtic mercenaries serving the Macedonian kings Philip II, his son Alexander the Great and their successors, were paid in gold staters which they took with them on their return to Northern Europe. Celtic chieftains thereafter minted their own coins modelled on them.

The ancient Greek city Lampsakos (Greek, Λάμψακος; today Lapseki in northwestern Turkey) was strategically located on the eastern side of the Hellespont (the Dardanelles; Turkish, Çanakkale Boğazı) in ancient Mysia. Founded by colonists from Phocaea and Miletus (Ionian cities on the western coast of Anatolia) in the 6th century BC. Despite being successively dominated by Lydia, Persia and Athens, it became a wealthy city, particularly famous for its wine, and began issuing coins early in its history.

| |

the goddess Hekate |

Originally known as Pityussa (Greek, Πιτυουσσα), its king Mendrom is said to have issued coins in the name of his daughter Lampsaka, and later the colonists renamed the city in her honour (a foundation myth perhaps). It was the first Greek city to issue gold coins on a regular basis, with as many as 40 different types minted over 60 years. The high quality of their staters, known as "lampsakians", led them to be widely circulated around the Mediterranean and Black Sea, transmitted and traded by Lampsakan seamen and merchants.

[The Phoceans were renowned as sailors, and Herodotus wrote that they were the first Greeks to make long sea voyages, reaching as far as the Adriatic, Tyrrhenia and Spain. They also founded Massalia (Marseilles, France) around 600 BC, Emporion (Empuries, Catalonia, Spain) around 575 BC and Elea (Velia, Campania, Italy) around 540 BC.]

Lampsakan coins as far back as 500 BC bore the image of the winged horse Pegasus, a tradition which continued until at least the first century BC when Roman imperial motifs began appearing on the coinage. The obverse sides usually depicted Greek deities (Demeter Chthonia, Zeus, Hera, Hekate, Athena) and the occasional Persian Satrap (Artabazos, 4th century Satrap of Daskylion/Phrygia). Some of the coin issues show a janiform (two-faced, like the Roman god Janus) female head in profile. Perhaps this is Hekate, or Lampsaka, who may have been a local patron deity or genius. |

| |

| |

Tetradrachm, Athens around 500 BC. |

The claim by Greek historian Herodotus (circa 485-425 BC) that "the Lydians were the first people we know of to strike coins of gold and of silver and to introduce retail trade", (Histories, Book 1, chapter 94) was probably a well-known tradition also mentioned by other writers, including the Lydian philosopher-poet Xenophanes of Colophon (circa 570-475 BC).

Modern scholars are in disagreement about exactly when and where money was first invented, with China, India and Persia among the contenders. Various objects, such as leaves, stones, seashells and lumps and bars of metal have been used as exchange tokens with their own intrinsic value all over the world since prehistory. Ancient decorated metal coin-like objects have also been discovered in many parts of the world, though whether they were used as money or for other purposes is hotly debated. There is also the question of how one defines a coin ... But let's not go there today.

During the 8-7th centuries BC, at the end of the "dark ages" in the Aegean region, gold and silver were much sought after and traded as far as Assyria. Lydia, in southwestern Asia Minor (Greek: Mikro Asias or Anatolia; today part of Turkey), was particularly rich in electrum, a natural alloy of gold and silver, from which the earliest coins were made. Gyges (reigned circa 716-678 BC or 680-644 BC), a usurper and founder of the Lydian Mermnad dynasty, is said to have owed his rise to power to his discovery of gold; a story which was transformed into a myth, related by Plato in The Republic, about a gold ring with magical powers. Two other kings in Asia Minor who possessed legendary wealth, were the Phrygian Midas and the Lydian Croesus (595 - ? BC, ruled 560-547 BC), and it is the latter who is credited with introducing the first gold coins and standardizing their purity.

| |

Drachma, Athens

around 500 BC. |

| |

Obol, Athens,

454-404 BC. |

Although many believe that coinage was invented in Lydia 650-600 BC, no coins of this period have yet been discovered by archaeologists in its ancient capital Sardis. The oldest supposed Lydian coin, the famous lion's head third stater [2], or trite, minted around 600 BC, was actually discovered in the ancient Greek city of Ephesus, although it was an ally of Lydia and taken in 560 BC by Croesus (after whom the "croesid" early Lydian coins are named). Older coins, dated to around 700 BC have been discovered on the Greek island of Aegina.

Stamped iron coins were also introduced as currencies separately by Sparta and the Ionian states around 700 BC. Their face value was guaranteed by legislation, and redeemable for their equivalent in gold or silver. The Ionian coins were badly made and easy to counterfeit, which led to adoption of silver and gold coins. The Spartan coinage, however, was in use until 350 BC when the economic influence of Athens' gold and silver overwhelmed the currency, despite a rear-guard state decree ordering that "no coin of gold or silver should be admitted into Sparta". [3]

So, a further debate rumbles on over whether coinage was introduced to Greece from Asia or vice versa. Why must everything be so complicated? Gives people something to talk about, I guess.

Lydia, at the time an expanding political and commercial empire (imperium and emporium), was geographically well placed for the exchange of goods and ideas between the Mediterranean and Asia. The idea of stamping fixed weights of metal to tranform them from commodity into currency rapidly spread through Greece and eastwards to Mesopotamia and Persia. Croesus of Lydia was defeated by the Persian king Cyrus in 547 BC, after which most of Anatolia became part of the Persian Empire until the time of "liberation" by Alexander the Great. It is thought that the Persians first adopted coinage after their conquest of Lydia.

The monetization of ancient economies has been credited with having had an enormous influence on the development of the city state (polis), the rise of oligarchies, democracy and other major political changes, and even on art, literature, philosophy and science, especially among the Greeks [4]. Portable coinage with a generally agreed value facilitated not only wholesale and retail trade within and between communites, the development of taxation and payment for goods, labour and services, but also helped buy the services of mercenaries as well as hoped-for favour among men and the gods.

Herodotus also tells us about the effect the invention of money had on Lydian family values and the world's oldest profession: "The daughters of the common people in Lydia prostitute themselves one and all to collect money for their dowries, and continue the practice until they marry." (Histories, Book I, 93) |

|

| |

Tetradrachm, Leontinoi, Sicily, around 475 BC. |

| |

| |

Leontinoi (Greek, Λεοντῖνοι; today Lentini in the province of Syracuse) in southeastern Sicily, was founded in 729 BC by colonists from Naxos (Νάξος), the oldest Greek colony in Sicily, which itself had been colonized by the Greek city of Chalcis in Euboea five years earlier. The settlers stole the fertile inland plain on which Leontinoi stood from the Sicels, the tribal people of central Sicily who gave their name to the island.

In 476 BC the tyrant Hieron I of Syracuse (Ἱέρων Α΄, ruled 478-467 BC, founder of the first Greek secret police) moved the inhabitants of Naxos and Katana (Κατάνη, another Naxian colony, today Catania, where the 6th century BC lawgiver Charondas wrote precise legislation in verse) to Leontinoi and repopulated Katana with Syracusans and Dorian Greeks from the Peloponnese. He also changed the name of Katana to Aetna (Αἴτνη), after the nearby volcano Mount Etna.

The Athenian playwright Aeschylus (Αἰσχύλος, circa 525-455 BC) produced his play The women of Aetna in honour of Hieron's founding of the city.

After Hieron's death, the Naxians repossessed the city in 461 BC, destroyed his tomb there and restored the name Katana. The Aetnans fled to the fortress of Inessa and took the name Aetna there with them.

This Tetradrachm (4 drachmas), called a "Leontinoi", dates from the reign of Hieron and must have been minted just after the forced move of the Naxians and Katanians to the city. A very well-made coin, its design is typical of the city's mintage. The obverse side shows a lion's head and the name Leontinoi, surrounded by four barleycorns, a sacred symbol of the ancient agrarian cult of Demeter and the Eleusinian Mysteries. The typical reverse side depicts a man driving a racing chariot drawn by four horses (a quadriga; Greek, τέθριππον, tethrippon), with Nike, the goddess of victory and sports shoes, flying above and offering him a victor's laurel wreath (as in the Syracuse tetradrachm below).

According to the Greek travel writer Pausanias (2nd century AD), Hieron won victories at the Olympic Games, once in the four-horse race and twice in the horse race, but died before he could fulfill his vow to dedicate offerings to Olympian Zeus as thanks. His son Deinomenes therefore commissioned the sculptor Onatas of Aegina to make bronze statues set up as votive offerings in Olympia, inscribed with the following dedication:

"Having won victories in thy grand games, Olympian Zeus,

Once with the four-horse chariot, twice with the race-horse,

Hieron bestowed on thee these gifts: his son dedicated them,

Deinomenes, as a memorial to his Syracusan father."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 42, sections 8-10. |

|

| |

Dekadrachm, Syracuse, Sicily, circa 400-370 BC. |

| |

| |

The powerful Sicilian city Syracuse (Greek, Συράκουσαι, Syrakousai; Italian, Siracusa), which Cicero called "the greatest Greek city and the most beautiful of them all", has such a long and prestigious history that it needs a couple of blogs to iself. Some other time, perhaps. If you are interested, see:

livius.org/su-sz/syracuse/syracuse_history01.html

At the time this coin was minted, conquests by the tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse (circa 432-367 BC, he started his ruthless career as an office clerk), aided by a personal army of mercenaries, were making Syracuse the power to be reckoned with in the area. During the same period, the Greeks of Sicily were engaged in a long, desperate war (which was to continue into Roman times) against the Carthaginians who had gained control of a third of the island. Tough times, high stakes, and lots of bloody money for the victors.

As a sign of the times, on this coin, below Nike and the quadriga (see the Leontinoi tetradrachm above) are the warlike motifs of armour on a ship's prow (some scholars have seen the form behind the armour as a spear), signifying either a naval victory or the trophies of a chariot race.

Many sources describe the obverse (front or recto, right) side of these coins as the reverse (back or verso, avers, left), and vice versa. See the Nike page in the MFP People section. |

|

| |

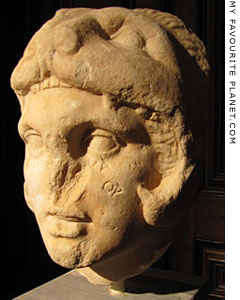

Silver tetradrachm, circa 310-275 BC, with a portrait of

Alexandros III of Macedonia (Alexander the Great) in

the guise of Herakles wearing the skin of a lion's head. |

| |

| |

Philip II of Macedonia (382-336 BC), Alexander's father, captured the gold and silver mines of Mount Pangaion in Northern Greece in 357 BC and those of Halkidiki (including at Aristotle's hometown of Stageira) in 348 BC, enabling him to mint high value coins and finance his further political and military ambitions. Alexander (356-323 BC) continued the coining tradition, and as well as capturing natural sources of precious metals he also gained huge hoardes as booty from his conquests in Greece and across Asia and North Africa. His coins were circulated throughout and beyond his empire, and copied for centuries after.

| |

Head of Alexander the Great

wearing a lion-skin [5].

Circa 300 BC. Found in

Kerameikos, Athens in 1875.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 366. |

Alexander's iconic portrait was not only influential but also powerful propaganda. Like the Persian darics, his coins depicted a strong warrior king, but now the message was conveyed with greater finesse and economy, concentrating on the head alone to broadcast the ruler's invincibility and charisma. The archetypal divine hero Herakles (known to the Romans as Hercules), son of Zeus, was revered under many names by several states and ethnic groups in the Mediterranean and Near East (e.g. the Phoenician Melqart, see below), many of whom claimed him as an ancestor or founder figure. The reverse side of the coins also depicted deities such as Zeus, Athena and Nike.

Alexander Tetradrachms (4 drachma pieces), minted at 26 locations within his empire, varied in size, but were generally 25-40 mm wide with a weight of 17.2 grams of silver. The coin in this photo, with its exceptionally high quality and fine detailing (the strongest Alexander portrait I have yet seen on a coin), is one of many "posthumous" tetradrachms, a variety of which were issued by as many as 61 mints long after Alexander's death, the last being produced around 65 BC at Mesembria, Thrace (today Nesebar on the Black Sea coast of Bulgaria). Unfortunately, the museum's labelling does not state the provenance of this coin, and as all the coins exhibited in the museum are pinned to the back of cabinets, clues such as mint marks on the reverse can not be seen. It seems a strangely old-fashioned way to display coins these days, especially given the amount of planning invested in the museum's recent redesign. Maybe it's all a question of money.

The website of the State Museums Berlin (SMB) now has a searchable online catalogue, the Münzkabinett - Online Catalogue, with images and details of items in its numismatic collection, including coins displayed in the Bode Museum and neighbouring Altes Museum and Neues Museum. Not all of the German texts are yet available in English.

According to the catalogue, this coin comes from Macedonia, northern Greece, weighs 17.11 grams and is 28 mm in diameter. The reverse side is marked "AΛEΞANΔPOY", and shows Zeus Aetophoros seated on a throne, holding a sceptre in his left hand. To his left is an eagle beneath which is a palm branch. |

|

| |

Mount Pangaion, Macedonia, Northern Greece. There's gold in them there hills.

See another photo of Mount Pangaion on Stageira & Olympiada page 1. |

| |

Stephanophore ("crown-bearer") tetradrachm, Aigai, Anatolia, after 190 BC. |

| |

| |

The ancient city of Aigai [6] (also Aigaiai; Ancient Greek, Αἰγαί or Αἰγαῖαι; on coins Αἰγαίεων; Latin, Aegae or Aegaeae; Turkish, Nemrutkale or Nemrut Kalesi, Nimrod Castle) stood on a mountain (today called Gün Dağı), 15 km east of the Aegean coast, and 35 km south of Pergamon. It was one of the 12 mainland cities of Aeolia, the region settled by Greeks, mainly from Thessaly and Boeotia (northeastern Greece), from around 1000 BC.

The Aeolians were typically farmers, in contrast to their more sea-going Ionian neighbours to the south. However their cities must have also benefitted economically from the trade routes between the Mediterranean and the hinterland of Anatolia (Asia Minor).

Aigai appears never to have been a particularly powerful or historically significant city, and its fate was similar to other cities in the area. It was part of Lydia which was conquered by the Persian Empire in 546 BC. After Alexander's "liberation" of Anatolia in the mid 4th century BC, the city was fought over by his successors. Eventually, in 218 BC it was taken by Attalus I of Pergamon. Attacked and destroyed by the Bithynian king Prusias II in 156 BC, it was rebuilt with the 100 talents compensation it received as a result of a peace treaty between Bithynia and Pergamon brokered by the Romans.

The Romans became masters of western Anatolia after the last Attalid king of Pergamon, Attalus III (circa 170-133 BC) bequeathed his kingdom and extensive territories to the republic. Aigai was again destroyed in 17 AD by a powerful earthquake which also wrought destruction at many places around the eastern Aegean. It was rebuilt with financial help from Emperor Tiberius.

Aigai minted its own coins from around 300 BC until the the middle of the 3rd century AD. This silver tetradrachm (4 drachms) is known as a "stephanophore" (crown-bearer) after the oak wreath on the reverse side within which Zeus stands, holding his symbols, an eagle and a sceptre. To the right of the god is the city's name ΑΙΓΑΙΕΩΝ, and to the left is the monogram ΠΑΩΙ. The obverse side shows a profile head of Apollo wearing a crown of laurel leaves and carrying a quiver and bow behind his neck.

The 35 mm diameter coin was made of 16.48 grams of silver. Dated by the Bode Museum to "after 190 BC", it is very similar to other tetradrachms from Aigai which have been dated elsewhere to 160-150 BC. It was during this time that, following the destruction by Prusias II, the city was rebuilt, under Attalus II of Pergamon, with many of the architectural and planning innovations known from Pergamon employed. The reconstruction programme included a temple of Apollo Chresterios (of oracles) which was associated with an ancient oracle outside the city. It is tempting to conjecture that these coins were minted with the 100 talents of silver it received as compensation. |

|

| |

| |

Shekel is a word of ancient Akkadian (after the city of Akkad; also known as Accadian or Assyro-Babylonian), a semitic language spoken and written in Mesopotamia alongside Sumerian. The language was supplanted around the 8th century BC by Aramaic. Dating back to the third millenium BC, the word shekel originally denoted a measure, probably of barley, of about 180 grains (11 grams). Eventually the word came to be used throughout the Semitic world, including Phoenicia, for weights used in trading. With the introduction of coinage, as we have seen, specific weights of metals stamped as coins became currency.

From 127 to 19 BC, during the Roman occupation, the Phoenician island city of Tyre (on the Mediterranean coast of modern Lebanon) struck silver shekels and half shekels with a purity of around 94% which became an important currency in the region. The shekels were also known as Tyrian tetradrachmas because they weighed 14.2 grams, about the same as four Athenian drachmas. |

|

Double Shekel, Tyre 104 / 103 BC.

Reverse side, with two overlapping

cornucopias (horns-of-plenty,

symbol of prosperity) with taenia. |

|

| |

The obverse side usually depicted the Phoenecian god Melqart (King of the City), also known as Ba'al Sūr (Lord of Tyre), and by the Greeks as the Tyrian Herakles. The reverse side showed an eagle on the bow of a ship and the legend "Tyre the Holy and City of Refuge". Some coins showed a double cornucopia, as in the coin above. The coin's inscription is in Greek (rather than Phoenician or Hebrew) since Greek was the official language of many states of the eastern Mediterranian and the lingua franca from the Hellenistic age and well into the time of domination by the Roman Empire.

Because of their purity and weight, silver Tyrian shekels were the only coins acceptable by the Jewish authorities for the payment of the Temple tax in Jerusalem. This was even the subject of a decree, recorded in the Talmud, despite the fact that the Tyrian shekels depicted craven images - and that of a pagan god into the bargain. According to the Torah (Old Testament, Book of Exodus, chapter 30: 11-16) this payment of a half-shekel by all Jewish men of 20 or older was introduced by Moses in 1289 BC: "Then shall they give every man a ransom for his soul to the Lord, when you number them; that there be no plague among them, when you number them." (Sounds like protection money.) The practice was banned by Emperor Hadrian in 135 AD and reintroduced by Jews in modern Israel in 1998.

The tax being a half-shekel, money-changers at the temple changed the shekels for half-shekels and Greek and Roman coins for the Tyrian at a fee of two kalbonot (a small Jewish coin worth half a dinar).

In the New Testament Christ is said to have paid the tax for himself and Simon Peter with "a shekel coin from a fish’s mouth". When the tax-collectors arrive, Jesus tells Simon Peter to "go to the sea and cast a hook and take the first fish that comes up, and when you open its mouth you will find a shekel. Take that and give it to them for me and for yourself." (Matthew 17: 24–27)

On another occasion though, Christ seems to have been so enraged by this money-changing business that he "went into the temple of God, and cast out all them that sold and bought in the temple, and overthrew the tables of the money-changers, and the seats of them that sold doves, And said unto them: It is written, My house shall be called the house of prayer; but ye have made it a den of thieves." (Matthew 21: 12-13)

This so-called "Cleansing of the Temple" incident appears to have been so significant that it is mentioned in all four Gospels of the New Testament. Legend has it that the "30 pieces of silver" paid to Judas Iscariot for his betrayal of Christ (Matthew 26: 14, 15) were also Tyrian shekels.

When the Romans closed the Tyrian mint in 19 BC, and began importing coins of only 80% purity, Jewish religious leaders were given special dispensation by Emperor Augustus (reigned 27 BC - 14 AD) to continue minting the coin solely for the purpose of paying the Temple tax, but only on condition that the coin retain its original pagan imagery. The priests considered that the weight and purity of the Tyrian shekel made it the only acceptable coin for the ancient tax. This consideration outweighed even the Second Commandment against idolatory, and the shekels continued to be minted for the tax between 18 BC and 65 AD.

The golden double shekel in this photo is finely made, and apparently quite rare. It does not conform to the usual iconography of Tyrian shekels. Cornucopias were common on coins from around the southeast Mediterranean (the Levant and Egypt), but gold coins of this quality showing overlapping cornucopias and the taenia (Greek: ταινία, "flat band" or "ribbon", a ceremonial headbinding) associated with sacred festivals, were minted in Alexandria from the 3rd century BC as special editions by the Ptolemies of Egypt [7]. The same motif has also been used on modern Israeli coins, including a 5 shekel piece (1981-1985), described as "Double cornucopia from a coin from the period of John Hyrcanus I (135-104 B.C.E.)". |

| |

Some of the

faces of Berlin's

Bode Museum.

Put your mouse

over an image to

see further details. |

| |

Michelangelo

Buonarotti |

| |

Sultan

Mehmed II |

| |

Alexander

von Humboldt |

| |

Victoria |

| |

Artemis |

| |

reliquary bust |

| |

sea monster |

| |

Egyptian

tomb relief |

| |

Mercury

and Psyche |

| |

Immanuel Kant |

| |

King Charles I |

| |

Saint Paul |

| |

Holy family

member |

| |

Christ child |

| |

Saint Catherine |

| |

Saint George |

| |

Saint Dionysius |

| |

Mary Magdelane |

| |

Apostle James |

| |

Saint Sebastian |

| |

Saint Dorothy |

| |

Anna Imhoff |

| |

Willibald Imhoff |

| |

French clergyman |

| |

The Devil |

| |

lion's head |

| |

serpent |

| |

hare |

| |

Byzantine mosaic |

| |

| |

| |

| |

The Bode Museum, Berlin |

|

|

The Bode Museum on the River Spree, Berlin

|

The Bode Museum (German, Bodenmuseum) is one of five museums, including the Pergamon Museum, on the northern end of Museumsinsel (Museum Island) in Berlin, Germany. Designed by architect Ernst von Ihne and completed in 1904, it was originally known as the Kaiser Friedrich Museum after Prussian Emperor Friedrich III, but renamed by the East German Communist authorities in 1956 in honour of its creator and first curator, Wilhelm von Bode (1845-1929).

The museum's collection includes sculpture and painting from the late Antique, Byzantine, Medieval and Renaissance periods, as well as the Numismatic Collection of coins and medals.

Along with Berlin's other major museums, the Bode Museum was damaged during the Second World War by Allied bombing and the street-to-street fighting between the remnants of the German defenders and the Soviet army in 1945. After the war, the collections of Berlin's museums were separated by the East-West division of the city. Since the reunification of Germany (1989) the collections have been gradually reorganized and the museums even more gradually renovated. The Bode Museum was closed for reconstruction in 1997 and reopened in 2006. It is now managed by the Berlin State Museums branch of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation.

Official website of State Museums at Berlin (SMB),

including information about current exhibitions, opening hours, etc.:

www.smb.museum |

|

| |

Equestrian statue of Prussian Emperor Friedrich III (1831-1888),

"the 99-day emperor", after whom the Bode Museum was originally

named, in the domed entrance hall of the Bode Museum, Berlin. |

| |

Persian daric, 5th - 4th century BC. Around 8.4 grams of purest gold.

Numismatic Collection, Bode Museum, Berlin.

Photo: Copyright © 2011 David John |

| |

Kindling the embers of the camp fire.

A soldier's wife cooks a pot of potatoes on the eve of a decisive European battle.

Detail from Frederick the Great before the Battle of Torgau

(Friedrich der Große vor der Schlacht bei Torgau) by the

Berlin historical painter Christian Bernhardt Rode (1725-1797).

Oil on canvass, 1791. Bode Museum, Berlin. |

|

| |

| |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

Since writing this blog in April 2011, further research and visits to Turkey and Greece, and particularly to the Numismatic Museum in Athens, have led to some revisions and additions to these articles.

David John, 22 May, 2011.

1. "Finally! A 100-kg Canadian gold coin", Canadian Broadcasting Corporation news article, Thursday, May 3, 2007.

cbc.ca/news/business/story/2007/05/03/goldcoin.html

2. See a photo of a Lydian electrum 1/6 stater at the British Museum

3. See: galmarley.com/framesets/fs_monetary_history_faqs.htm

4. See: Richard Seaford, Money and the early Greek mind: Homer, philosophy, tragedy. Cambridge University Press, 2004. Limited preview at Google books

5. This Head of Alexander the Great and other items from National Archaeological Museum, Athens, are currently on display in the exhibition "Myth and Coinage", 15 April - 27 November 2011, at the Numismatic Museum, 12 Elftherios Venizelou (Panepistimiou) Street, Athens, Greece. www.nma.gr

6. Aigai, Aeolia, now in Manisa Province, western Turkey. Not to be confused with other ancient cities of the same name which also minted coins: Aigai (Αιγαί, today Vergina, northern Greece), capital of Macedonia before Pella; Aigeai (also known as Aegea, Aegeae or Aigai, today Ayas, southeast Turkey) in Cilicia (Greek: Κιλικία, Turkish: Kilikya).

I must admit to having been confused by the spelling on the museum's labelling and consequent research. I apologize to readers who may have been equally confused (or annoyed) by the first version of the article about Aigai on this blog, which has since been rewritten.

As ever, we welcome comments and criticisms on these and all other articles on My Favourite Planet. Please feel free to get in contact and put us right if we have erred. |

|

|

| |

|

7. Decadrachm of Ptolemy III Euergetes,

246-222 BC, depicting a cornucopia.

From the exhibition "Myth and Coinage",

Numismatic Museum, Athens, Greece.

See note 5 above. |

|

Articles and photos copyright © David John 2011

The Cheshire Cat Blog at My Favourite Planet Blogs

We welcome considerate responses to these articles

and all other content on My Favourite Planet.

Please get in contact.

The photos on this page are copyright protected.

Please do not use them without permission.

If you wish to use any of the photos for your website,

blog, project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

Views of blog authors do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers

or anyone else at, on or in the vicinity of My Favourite Planet. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms

in Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr |

| |

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece +30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de |

| |

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece +30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr |

| |

| |

|