|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Macedonia > Stageira & Olympiada |

| Stageira & Olympiada |

History of Stageira & Olympiada - Part 2 |

|

|

page 3 |

|

|

| |

Part of a historical map (1908) showing the location of Ancient Stageira in Halkidiki (see history Part 8). |

| |

History of Ancient Stageira - Part 2

Foundation, 7th century BC |

| |

Between the 8th and 6th centuries BC there was a great wave of Greek colonization around the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, particularly in the North Aegean, Italy and Sicily. Most colonies were built on islands and along coasts, and early colonists seldom ventured far inland.

Typically, a Greek mother city-state, literally the metropolis (Greek, μητρόπολις; μήτηρ, meter, mother and πόλις, polis, city), would send a group of citizens to a location to form a colony, an apoikia (ἀποικία), led by an oikistes or oikistai (οἰκιστής, plural οἰκισται). [2]

During this period Greeks also established trading posts, emporia (ἐμπόριον, emporion; plural ἐμπορία, emporia), on the territory of foreign nations, such as Sais in Egypt.

Before sending out colonists, the metropolis would usually consult the Oracle of Delphi to ensure a favourable outcome for their enterprise.

The mother city-states of colonies not only gained new territories, resources, harbours and trade centres, as well as other political, military and economic advantages, they were also able to ease tensions caused by competition for limited land and resources at home, as populations grew during what has become known as the "renaissance of Greece", following the "Dark Ages" which lasted from the collapse of Mycenean civilization during the 12th century BC until the start of the Archaic period in the 8th century BC.

Excess populations were simply exported; and a critical mass of several hundred colonists were required to take land from the natives, by force where necessary, and to build, run and defend it. This helps explain the need for massive defensive walls around cities such as Stageira (see Ancient Stageira gallery pages 8-17).

Another spur to colonization was the drought which afflicted southern Greece at the end of the 8th century BC. Halkidiki (or Chalkidiki, Chalcidice; Greek, Χαλκιδική) offered an attractive target, with its fertile soil, mild climate, good water supplies, abundance of hunting prey, timber as well as minerals such as gold and silver. [3]

Before the arrival of Greek colonists from the 8th century BC, the area around Halkidiki, including what was to become eastern and much of central Macedonia, was dominated by Thracian tribes. It is thought that some Ionian tribes from southern Greece had already settled here in the 11th century BC, during the Bronze Age, and apparently co-existed peacefully with the Thracians.

Euboeans from the city-states of Chalcis (or Halkis, Ancient Greek, Χαλκίς; modern name Χαλκίδα, Chalkida) and Eretria came to dominate the peninsula, and the Chalcidians and lent their name to it. [4] Early attempts by Chalcidians to settle on the peninsula failed due to opposition by local tribes, until the colonists united to found the powerful city of Olynthos ( [5], but see also [6]). Some "barbarian" tribes, such as the Bottiai and Bisalti, were still living in Halkidiki in Classical times. [7] |

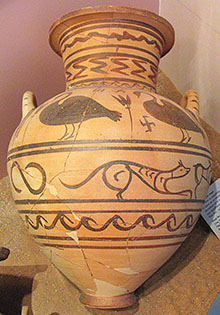

Funerary urn with painted

decoration, from Halkidiki.

8th - 7th century BC.

Thessaloniki Archaeological

Museum. |

| |

Funerary urn decorated with

birds and hunting dogs.

8th - 7th century BC.

Thessaloniki Archaeological

Museum.

photos: © David John |

| |

| |

Political conflicts between Chalcis and Eretria, which culminated in the Lelantine War on Euboea (circa 710-650 BC), weakened both cities and their ability to found new colonies. It is thought that Chalcis therefore assisted the Andrians to establish the colonies at Stageira, Akanthos, Sane (at the northwest end of the Athos peninsula) and Argilos (near the River Strymon [8]).

Andros had been long dependent on Eretria, but it seems that as a result of the drought and the Lelantine War, the Eretrians had lost control of the island. It may be that the Andrian colonists had thus become allies of Chalcis.

However, the Greek historian Plutarch tells us that the Chalcidians disputed the Andrians' claim to Akanthos [9]. Plutarch's explanation of the Chalcidian take-over of the city may be a later interpretation of a founding legend. They also took Stageira, and according to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, they claimed to have founded the city. [10]

What became of the Andrians in these cities? Where they forced to leave or did they learn to live with the Chalcidians? No written evidence of contact between Andros and the new colonies has yet been discovered. It also appears significant that both Stageira and Akanthos, which had access to local sources of silver and gold, minted coins from the 6th century BC (Stageira issued staters as early as 530 BC, and Chalcis around 550 BC), whereas Andros did not begin producing coinage until much later. [11] Either relations between Andros and the colonies were severed early on, or the Andrian colonists had left.

There appear to be no references to Andrians in connection with Stageira beyond the time of its foundation, although the historian Thucydides was still referring to the the city as an Andrian colony at the end of 5th century BC ( [28] history part 5). Perhaps he and later authors were merely repeating a tradition concerning the Archaic colonizations. |

|

| |

| |

Ancient Stageira

the birthplace of Aristotle

by Dr. Kostas Sismanidis

Dr. Kostas Sismanidis led the first

systematic archaeological excavations

of Stageira, which began in 1990.

His illustrated 20-page booklet contains

a brief history of Stageira and Olympiada

and provides a useful guide to the main

features of the archaeological site.

The booklet includes a plan of the site

and photos of finds which are now in the

Archaeological Museum of Polygyros.

Very little has yet been published about

Ancient Stageira, so this excellent booklet

remains the essential guide for the general visitor as well as those who wish to gain a deeper understanding of the place.

Available free

in English, German and Greek from

Hotel Germany and Hotel Liotopi,

Olympiada. |

|

| |

| |

| |

Votive relief depicting a symposium. Two reclining heroes are served by a young wine-pourer.

From Potidaea (renamed Cassandreia in 316 BC, see History part 6), Halkidiki, circa 380 BC.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Stageira &

Olympiada

History

part 2 |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

2. Apoikia and oikistai

An apoikia (ἀποικία, away from home; plural ἀποικίαι, apoikiai) was a settlement of apoikoi: persons who live (oikein) away from or separated from (apo) their homeland. Apoikia has also been translated as "home away from home". The settlers were led by an oikistes or a number of oikistai (οἰκιστής, hearth-founder; plural οἰκισται), who were considered the founders of the new city.

3. Ancient Greek colonies

See: N. G. L. Hammond, A history of Greece to 322 BC, chapter 2, section 1. Oxford University Press, 1959.

For further discussion on the drought in the 8th century BC, see:

John McK. Camp II, A drought in the late 8th century BC. In: Hesperia, Volume 48, No. 4 (October - December 1979), pages 397-411. American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

4. The origin of the name of Halkidiki

The name Halkidiki has been translated as "according to the custom or law of Chalcis", or "the way of Chalcis", inferring that the Chaldician colonists followed the customs and laws of the mother city, or were afforded the rights established by them. From dikē (Δίκη), justice, fair judgement.

Dike was the Greek goddess of Justice. See Dike at theoi.com.

Very few scholars seem to give credence to the theory that Halkidiki was the name of a Greek tribe native to the area before the colonization by Euboeans.

See: E. Harrison, Chalkidike. Classical Quarterly, 1912, 93 ff., 165 ff.

Harrison's theory was resurrected in the 1970s, but with very weak arguments.

See: S. C. Bakhuizen, R. Kreulen, Chalcis-in-Euboea, Iron and Chalcidians Abroad, Chapter 3: Chalcidian colonization, p. 14. Studies of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. V, Chalcidian Studies III. Brill Archive, Leiden, Netherlands, 1976. |

|

5. Strabo on Macedonia and the colonization of Halkidiki

Strabo (Στράβων, Strabon; 64/63 BC – circa 24 AD), Greek geographer, philosopher and historian from Amaseia in Pontus (today Amasya, Turkey).

"But of all these tribes [of Macedonia - Bisaltae, Edones, Mygdones, Sithones] the Argeadae, as they are called, established themselves as masters, and also the Chalcidians of Euboea; for the Chalcidians of Euboea also came over to the country of the Sithones and jointly peopled about thirty cities in it, although later on the majority of them were ejected and came together into one city, Olynthus; and they were named the Thracian Chalcidians."

Strabo, Geography, Book 7, fragments, 11. At Perseus Digital Library.

"... these cities [of Euboea] grew exceptionally strong and even sent forth noteworthy colonies into Macedonia; for Eretria colonized the cities situated round Pallene and Athos, and Chalcis colonized the cities that were subject to Olynthus, which later were treated outrageously by Philip... These colonies were sent out, as Aristotle states, when the government of the Hippobatae, as it is called, was in power; for at the head of it were men chosen according to the value of their property, who ruled in an aristocratic manner."

Strabo, Geography, Book 10, chapter 1, section 8. At Perseus Digital Library.

The Geography of Strabo, edited by H. L. Jones. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.;

William Heinemann Ltd, London. 1924. At Perseus Digital Library.

6. Herodotus on the Chalcidian possession of Olynthos

Herodotus tells us that at the time of of the Second Persian invasion of Greece (483-479 BC), Olynthos, which was to become the most powerful city in Halkidiki in Classical times (see History part 5), was in the hands of the Bottiai, a local Thracian tribe. After Xerxes left Greece, Artabazos, one of his generals, suspecting that Olynthos was about to join the Corinthian colony of Potidaia in revolt, conquered the city in the winter of 480-479 BC, killed the inhabitants and gave the city to the Chalcidians.

"Thereupon Artabazus laid siege to Potidaea, and suspecting that Olynthus too was plotting revolt from the king, he laid siege to it also. This town was held by Bottiaeans who had been driven from the Thermaic gulf by the Macedonians. Having besieged and taken Olynthus, he brought these men to a lake and there cut their throats and delivered their city over to the charge of Critobulus of Torone and the Chalcidian people. It was in this way that the Chalcidians gained possession of Olynthus."

Herodotus, The Histories, Book VIII, chapter 127, section 1. English translation by A. D. Godley.

Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1920. At Perseus Digital Library.

7. Diodorus on "barbarian" tribes in Halkidiki

Diodorus Siculus (Διόδωρος Σικελιώτης, Diodoros Sikeliotes; also known as Diodorus of Sicily) was a Greek historian from Agyrion in Sicily (today Agira), who lived during the 1st century BC. Almost nothing is known of his life except that he appears to have spent some time in Rome and Egypt. He wrote his enormous 40 volume universal history Bibliotheca historica around 60-30 BC. Only books 1–5 and 11–20 have survived, with fragments and excerpts of the lost books preserved in works of later authors.

In his account of the Peloponnesian War, he mentions the presence of Thracian tribes in and around Halkidiki when dealing with the campaign of the Spartan general Brasidas in the area in 424-422 BC (see History part 5):

"And when all his preparations had been made, he set out from Amphipolis with his army and came to Acte [the Athos peninsula], as it is called, where he pitched his camp. In this area there were five cities, of which some were Greek, being colonies from Andros, and the others had a populace of barbarians of Bisaltic origin [a Thracian tribe], which were bilingual. After mastering these cities Brasidas led his army against the city of Torone, which was a colony of the Chalcidians but was held by Athenians."

Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes with an English Translation by C. H. Oldfather. Vol. 4-8. Book 12, chapter 68. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.; William Heinemann Ltd, London. 1989. At Perseus Digital Library.

8. Ancient Argilos

The site of Argilos is on the north Aegean coast, 13 km of east Asprovalta, 4 km west of the Strymon delta, and 7 km southwest of Amphipolis. It is currently being excavated by a Greek-Canadian archaeological team, as a collaborative project between the Ephoria of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities of Kavala and the University of Montreal. See the project's excellent website: www.argilos.org (in English, French and Greek). |

|

9. Plutarch on the dispute between the Andrians and Chalcidians over Akanthos

Plutarch (Greek: Πλούταρχος; name as Roman citizen Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, Μέστριος Πλούταρχος, circa 46-120 AD), Greek historian, biographer and essayist, born in Chaeronea, Boeotia.

Aetia Graeca (Greek Questions or Causes) is a collection of 113 explanations of Greek folklore customs and names. One of his main sources is thought to have been the writings of Aristotle.

"30. What is the 'Beach of Araenus' in Thrace?

When the Andrians and Chalcidians sailed to Thrace to settle there, they jointly seized the city of Sane, which was betrayed to them; but when they learned that the barbarians had abandoned Acanthus,

they sent out two scouts.

When these were approaching the city, they perceived that the enemy had all fled; so the Chalcidian ran forward to take possession of the city for Chalcis, but the Andrian, since he could not cover the distance so rapidly as his rival, hurled his spear, and when it was firmly implanted in the city gates, he called out in a loud voice that by his spear the city had been taken into prior possession for the children of the Andrians.

As a result of this a dispute arose, and, without going to war, they agreed to make use of Erythraeans, Samians, and Parians as arbitrators concerning the whole matter. But when the Erythraeans and the Samians gave their vote in favour of the Andrians, and the Parians in favour of the Chalcidians, the Andrians, in the neighbourhood of this place, made a solemn vow against the Parians that they would never give a woman in marriage to the Parians nor take one from them. And for this reason they called the place the Beach of Araenus, although it had formerly been named the Serpent's Beach."

Plutarch Aetia Graeca (Greek Questions), 30. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. Originally published in Plutarch's Moralia, Volume IV, pages 1–249. The Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1936. at sacred-texts.com.

10. Dionysius of Halicarnassus on Aristotle

Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Greek, Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνᾱσσεύς, Dionysios son of Alexandros of Halikarnassos, circa 60 BC – after 7 BC), Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric during the reign of Emperor Augustus.

His literary letter, the First Letter to Ammaeus, in which he refutes claims that the Athenian orator Demosthenes was influenced by Aristotle's writings on rhetoric, contains one of the oldest surviving biographies of the philosopher. He is among the ancient writers who states that Aristotle's mother was descended from the Chalcidian founders of Stageira.

"Aristotle was the son of Nicomachus, who traced his lineage and his profession back to Machaon, the son of Asclepius [i.e. follower of Asklepios; medical doctor]. His mother, Phaestis, was descended from one of those who led the colony to Stageira from Chalcis.

He was born in the ninety-ninth Olympiad, when Diotrephes was archon at Athens, and was, therefore, three years older than Demosthenes.

In the archonship of Polyzelus, after the death of his father, he went to Athens, being then eighteen years of age. Having been introduced to the society of Plato, he spent a period of twenty years with him.

When Plato died, in the archonship of Theophilus, he went to the court of Hermias, the tyrant of Atarneus, and spent three years with him before retiring to Mytilene in the archonship of Eubulus.

Thence he proceeded, during the archonship of Pythodotus, to the court of Philip, and spent eight years there as Alexander's tutor.

After the death of Philip, in the archonship of Evaenetus, he returned to Athens, and taught in the Lyceum for a period of twelve years.

In the thirteenth year, after the death of Alexander in the archon-year of Cephisodorus, he set off for Chalcis, where he fell ill and died at the age of sixty-three.

Such, then, are the records transmitted to us by the biographers of Aristotle."

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, The three literary letters, Ep. ad Ammaeum I, Ep. ad Pompeium, Ep. ad Ammaeum 2. First Letter to Ammaeus (I Epistula ad Ammaeum), V-VI, pages 61-63.

In Greek and English, edited and translated by William Rhys Roberts (1858-1929).

Cambridge University Press, 1901. At the Internet Archive. |

|

11. Relations between Andros and its colonists in Halkidiki

See: Gocha R. Tsetskhladze (Editor), Greek Colonisation, an account of colonies and other settlements overseas, Volume 2; Chapter 1, Greek Colonisation of the Northern Aegean by Michalis Tiverios. Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, Netherlands, 2008.

See coins of Stageira and Akanthos on History of Stageira part 3 (next page). |

|

|

Photos, maps and articles: copyright © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: copyright © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide

comprehensive and accurate information across this

website. However, we can take no responsibility for

inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services

mentioned on these pages. |

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|