|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Macedonia > Stageira & Olympiada |

| Stageira & Olympiada |

History of Stageira & Olympiada - Part 7 |

|

|

page 8 |

|

|

| |

The site of the ancient city of Stageira on the Liotopi pensinsula. |

| |

History of Ancient Stageira - Part 7

From the Roman period to the present day |

| |

So what happened to the inhabitants of Stageira? Were they resettled at Cassandreia or Thessaloniki, or did they move somewhere else when the gold and silver ran out? As we have seen throughout this history, inhabitants of cities were sent to colonies, conscripted into armies, taken off en masse to work elsewhere, or massacred or enslaved by invaders and pirates.

Macedonia and Halkidiki were certainly caught up in many wars and invaded several times right into the 20th century. The invaders include Romans, Goths, Huns, Normans, Franks, crusaders, Bulgarians, Serbians, Venetians, Turks and Nazi Germany. Some invaders were bent on conquest, others merely on destruction, plunder and enslavement of local populations. Later, others still, such as the Slavs, Albanians and Turks established settlements in the area and lived for centuries in peace with the Greeks.

Roman and Byzantine empires,

168 BC - 1453 AD

Following the various wars during the 155 years after Alexander the Great's death, Macedonia was eventually conquered by Rome in 168 BC. At first it was divided into four subject, self-governing republics or cantons (Greek, μερίδες, merides; Latin, regiones), but around 148-146 BC it became a single Roman province, Provincia Macedonia (Greek, Ἐπαρχία Μακεδονίας, Eparchia Makedonias), with Thessaloniki as its capital.

The Romans also fought their wars in this area, and Brutus and Cassius, two of Julius Caesar's assassins, based their fleet at Neapolis (Kavala) before the decisive Battle of Philippi against Mark Antony and Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) in 42 BC.

In the late 140s BC the Romans began building the Via Egnatia [45], the first highway across the Balkan peninsula to Byzantium. Passing Thessaloniki, the road crossed the north of Halkidiki on its way to Stavros (15 km north of Stageira, see below), Argilos, Amphipolis and Neapolis. The Romans, and later the Byzantines, Venetians and Turks, built fortresses and watchtowers along the trade and military routes by land and sea. The remains of many of these are still visible around Macedonia and Thrace. [47]

After Emperor Constantine established Byzantium (later known as Constantinople, today Istanbul) as the new capital of his empire in 330 AD, Macedonia became part of the increasingly Christianized Byzantine Empire. A small castle was built on the North Hill of Stageira, which by the Middle Ages had become known as Livasdias or Lipsada. [48] The remains of the Middle Byzantine fortifications (10-11th centuries AD) can still be seen at Stageira (see Ancient Stageira gallery pages 30-33 and 36-37).

Remains of Byzantine buildings have also been found on the island of Kapros (see Olympiada gallery page 3).

The fortifications at Stageira were part of a network of defenses guarding land and sea routes between Thessaloniki and Constantinople, as well the eastern approach to Halkidiki and the monasteries of Athos. |

|

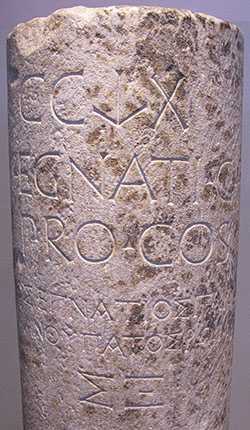

Via Egnatia milestone.

146-100 BC. [46]

Thessaloniki

Archaeological Museum. |

|

|

Ottoman Empire, 1453 - 1913 AD

By 1430 Macedonia was under the control of the Ottoman Turks, and with the fall of Constantinople in 1453 the Byzantine Empire was replaced by the Ottoman. People from Turkey and the Balkans moved into Macedonia, often reinhabiting ancient towns and villages. Halkidiki, however, remained mainly Greek. The British topogorapher, William Martin Leake, who travelled around northern Greece at the beginning of the 19th century, visiting Halkidiki in autumn 1806, wrote:

"Notwithstanding the mass of ignorance collected in the monasteries of the Oros [Agios Oros, Holy mountain = Mount Athos], some recollections of ancient history are still preserved here. This may be attributed in great measure to the Chalcidice and its three smaller peninsulas being inhabited by Greeks unmixed either with the Bulgarian or Albanian race, and having very few Turks among them." [50]

Leake also wrote that local people at Stratoni believed that their village was "η πατρίδα του Αριστοτέλους, or the native town of Aristotle". He rightly suspected that they were incorrect, and that it was the site of the ancient city Stratonikeia. Likewise, he refuted the theory, current among European scholars, that nearby Nizvoro (or Isvoro, Ίσβορο, today Stratonike) was the location of Ancient Stageira. This scholarly muddle helps explan why, in 1924, the village Kazantzi Machala (Καζαντζή Μαχαλά) was mistakenly renamed Stageira, and Nizvoro was renamed Stratonike (see map and further information in History Part 8). On the other hand, he believed that Ancient Stageira was located at Stavros, 15 km to the north of Olympiada. [51] |

| |

William Martin Leake

[49] |

| |

He was the first intellectual in modern times to visit and report on Olympiada. When he arrived at the village, then known as Lybjádha, on 5 November 1806, he learnt from a local the connection of the place's name with Alexander the Great's mother Olympias, and was taken to the site of Stageira (though he was unaware of its identity), where he saw the remains of the Classical walls. He recognized the island Kafkanas as the ancient Kapros, and the harbour, then known as the Skala (a common name for Greek harbours, such as Skala on Patmos), as the port of Stageira mentioned by Strabo. [52] He also reported on the gold and silver mining activities in the area, and mentioned the numerous large slag heaps from the mines at Olympiada. [53]

It is to Leake's great credit that he actually faced the perils of travel in the early 19th century to get out there and explore the landscapes of Greece and Turkey for himself, rather than being content with armchair archaeology or theoretical debate. He was an important pioneer in the investigation of ancient topography, and he undertook it without the ambition of self-enrichment or the intention of plundering antiquities. He was steeped in ancient history, had a scientific mind and a keen eye, but even he failed to perceive the ancient city buried on the two hills of the Liotopi peninsula. So it is not surprising that others were unable to identify Stageira for so long, and that its true location remained merely the subject of scholarly debate from the 17th century until the end of the 20th (see a discussion of historical maps in History part 8).

Meanwhile, it seems life continued in a small way around Olympiada, with mining and farming, and the harbour was used for shipping timber. However, life remained perilous. Throughout history the Mediterranean was plagued by pirates who robbed ships and raided coastal villages (see photo on previous page).

Inland, robber bands attacked travellers on the roads of northern Greece during Ottoman times and into the early 20th century. Inhabitants of the vast Ottoman Empire were also prey to the whims of the sultans and their corrupt local officials, who fleeced their subjects with taxes and punished dissenters with vicious cruelty. |

|

|

|

Greek and Macedonian independence, 1821 - 1913 AD

The Greek War of Independence began in 1821, and by 1829 much of mainland Greece and many islands had been liberated from Ottoman rule. However, Macedonia only became part of in Greece in 1913 after the Balkan Wars. During the First World War, Greece gave up its neutrality to side with the Allies against Germany, Austria, Turkey and Bulgaria, in return for a promise of allied help in its territorial claims to Greek-inhabited areas of Thrace and Asia Minor. [54] |

|

|

|

Refugees and rediscovery, 1923 - today

After the war, the Allies' promises dissolved, nevertheless the Greeks, without outside assistance, made a desperate and ultimately futile attempt to drive the Turks out of areas such as Smyrna (today Izmir, Turkey) during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922. The failure of these uprisings proved catastrophic for the peoples of the southern Balkans and the Aegean. As a result of the ensuing Treaty of Lausanne, signed in 1923, there was massive forced population exchange between Greece and Turkey. |

|

|

So it was that in 1923-1924 Greek families from the village of Agia Kyriaki (Αγια Κυριακη), near Izmit (ancient Nicomedia, Bythinia, see Olympiada gallery page 17), in northwestern Anatolia, arrived as refugees in the tiny farming village of Olympiada. They are said to have found ten families already living in the marshy area a little further inland of the modern village. The mosquito-infested marshes were the source of malaria which caused the death of nearly a third of the first refugees, and others were relocated to other places in Macedonia and Thrace. (You will be happy to know that there is no longer malaria in Olympiada.)

Among the refugees from Agia Kyriaki who were moved to Macedonia was the family of Menelaos Loundemis (1912-1977), who was to become one of Greece's best known modern poets (see Olympiada gallery page 6).

Life was hard for the refugees, many of whom arrived with only what they could carry. Greeks had lived in Asia Minor for nearly 3,000 years, and although Greece was considered the spiritual home to those in the diaspora (which included countries around the Black Sea, the Levant, Egypt and North Africa), the new nation was in fact a foreign land.

The small fledgling state already had its problems. The wars had left deep scars and disrupted age-old infastructures. Not only had it lost many of its trading partners, significantly Turkey itself (which particularly affected the economies of many of the islands), it also lost most of its Turkish inhabitants, who, for good or ill, had been part of the economy and culture for four centuries. |

|

Menelaos Loundemis,

bust in Olympiada. |

|

The sudden influx of masses of refugees was a heavy load for Greece, as ever embroiled in its own internal political turmoil, on the eve of an international depression and yet another war. The political and economic situation was to deteriorate considerably during decades of dictatorships and fascist occupation, and were not to improve until the return of democracy and membership of the European Union in the 1980s.

The new Olympiadans, however, got on with building their new home, and a pretty good job they made of it too. Today Olympiada is a pleasant and friendly rural village, with a solid community, and without the glitz that has infected other seaside resorts.

Aware that they were living in the hometown of Aristotle, the inhabitants of Olympiada badgered the Greek Archaeological Service for many years, trying to get officials to take an interest in the place. It took the chance find by an amateur diver of an unfinished Archaic kouros statue in the small harbour of Liotopi in the 1960s to attract the attention of the archaeologists.

In 1968 Dr. Fotios Petsas, who was at the time director of the Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, [55] arrived at Olympiada to investigate the area. Dr. Petsas spent just a few days here making small excavations, paid for by the people of Olympiada. There followed other investigations at the small bay of Sykia, which revealed the remains of Classical walls, and at Vina, 1.5 km south of Stageira, where a circular tower was discovered.

It was to take over 20 years before the further work was to be done at Stageira. Finally, in September 1990, Dr. Konstantinos L. Sismanidis (Κωνσταντίνος Λ. Σισμανίδης) of the Greek Archaeological Service (the 16th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities) was able to begin a serious campaign of excavation. After clearing away the sand, soil and vegetation which had kept the ancient city hidden from the world for centuries, Dr. Sismanidis was able to reveal to the world that the home of Aristotle had finally been rediscovered.

The investigations which Dr. Sismanidis began are still going on, and you can see some of the results in the Ancient Stageira gallery. |

|

|

| |

A relief depicting a family riding in a horse (or mule) drawn wagon. Part of an

inscribed stele from Thessaloniki, Roman Imperial period, 1st - 2nd century AD.

Traces of paint are still visible on the edges of the figures.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Stageira &

Olympiada

History

part 7 |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

45. Via Egnatia

The Roman Via Egnatia (Greek, Ἐγνατία Ὁδός), the first highway across the Balkan peninsula, was built between the late 140s and 100 BC, and named after Gnaeus Egnatius, proconsul, governor of Macedonia.

A continuation of the Via Appia between Rome and the southeastern Italian Adriatic port of Brindisium (Brindisi), it joined the Illyrian port of Dyrrachium (the Corinthian colony Ἐπίδαμνος, Epidamnos; today Durrës, Albania) with Byzantium. Passing Pella and Thessaloniki, it crossed the north of Halkidiki on its way to Stavros (15 km north of Stageira), Argilos, Amphipolis and Neapolis (Kavala).

The Via Egnatia acquired a number of branches to connect towns off the main route, and a further network of roads was also built to places north and south as the Roman Empire expanded through Greece and the Balkans.

See an illustrated article about walking the section of the Via Egnatia at Kavala, including more photos of milestones, on Activities and sightseeing in Kavala.

46. Milestone of the Via Egnatia

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. AE 1976. 443.

Grey-greenish marble. Height 131 cm.

Found beneath 7 metres of alluvial sand during the construction of the Elliniki Viomichania Ochimaton factory (Ελληνική Βιομηχανία Οχημάτων, ΕΛΒΟ, Hellenic Vehicle Industry, ELVO) in the Industrial Area of Sindos (Σίνδος), 10 km northwest of Thessaloniki.

The bilingual inscription in Latin and Greek on the milestone mentions Gnaius Egnatius. The distance of 260 (= CCLX = ΣΞ') Roman miles corresponds to the distance from Dyrrachium to the Gallikos River (Γαλλικός, the ancient Echedoros, Εχέδωρος; known in the Middle Ages as Gomaropnichtis, Γομαροπνίχτης), west of Thessaloniki, where the stone was found. The total distance covered by the Via Egnatia was about 1,120 km (696 miles; 746 Roman miles).

Latin inscription:

CCLX/Cn(aeus).Egnati(us).C.(filius)/pro.co(n)s(ul) |

|

Inscription on a Via Egnatia milestone.

146-100 BC.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum.

photo: © David John |

|

|

47. Ancient and Medieval towers in Macedonia and Thrace

Thessaloniki and Kavala have the largest surviving ancient and medieval fortifications in Macedonia; the walls of Thessaloniki are the second-longest surviving city walls in Europe, after the those of Constantinople (Istanbul). Along the road which connects them (the old national road which roughly follows the route of the Via Egnatia) there are several old towers to be seen, for example at the hillside village of Vrasna, about 18 km north of Olympiada, to the northwest at Rentina (a medieval castle near Lake Volvi), and to the northeast on the River Strymon near Amphipolis. On the west coast of Halkidiki, a Roman tower can be seen at Nea Potidea (ancient Potidaea, renamed Cassandreia in Hellenistic times). North of the main Via Egnatia, are remains of fortifications at Serres, Siderokastro, and in Thrace at Didymoteicho.

48. Stageira known as Livasdias or Lipsada in Middle Ages

In his booklet Ancient Stageira, the birthplace of Aristotle (see History part 1), Dr. Kostas Sismanidis states that there is a medieval source for the name. This source is probably the imperial chrysobull (golden bull) issued in 1079 AD by Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros III Botaneiates (Νικηφόρος Βοτανειάτης, circa 1002-1081, emperor 1078-1081).

Unfortunately, we have been unable to research this more thoroughly or find other literary sources which mention Stageira or Olympiada during the Byzantine or Ottoman periods.

If you know of any such sources, please get in contact.

49. Leake portrait

Colonel William Martin Leake (1777-1860), British topographer, antiquarian and author; Fellow of the Royal Society and expert in marine artillery.

Image source: Alfred Gudeman, Imagines philologorum, Teil 5. Druck & Verlag von B. G. Teubner, Leipzig & Berlin, 1911. At telemachos.hu-berlin.de (Humboldt University, Berlin).

50. Leake says Halkidiki inhabited mostly by Greeks

William Martin Leake, Travels in Northern Greece Volume 3, Chapter XXV, pages 159-160.

Published in four volumes, Rodwell, London, 1835. At archive.org.

See also an ethnographical map of Halkidiki from 1914, and a short discussion about the ethnic situation in Macedonia in History of Stageira and Olympiada - Part 8.

51. Leake: Stavros as the location of Stageira

In the 19th century the village of Stavros occupied the hillside location now known as Ano (Upper) Stavros. The main part of modern Stavros, below it, is a seaside resort and port. It is now thought that Stavros was the location of ancient Bromiskos, mentioned by Thucydides (see History part 8).

Leake's belief was quite a resonable one, particularly given Strabo's inflated figure for the distance between Akanthos and Stageira (see Olympiada gallery page 3). However, he should have considered that the distance between Stageira and its port Kapros would thus be quite considerable. Why would the Stageirites locate their main port so far away when Stavros has its own harbour? |

|

|

|

52. Leake's visit to Olympiada

For the quotations by the Greek geographer Strabo concerning Stageira, see Olympiada gallery page 3.

On 5 November 1806 Leake travelled by horse from Nizvoro (today Stratonike, see History part 8) to Stavros, stopping briefly at Olympiada.

"All the forenoon we travel amidst the clouds, which, as the wind is to the south-east, hang low upon the hills, and at 6.30 descend upon the southern corner of the plain of Lybjádha, around which all the sides of the hills are covered with great heaps of scoriae [slagheaps from the mines], similar to those near the Madén of Nizvoro, but much larger and more numerous.

The plain, which is a dead level in the form of an equilateral triangle, surrounded by woody mountains, is covered with fields of kalambokki, and intersected with torrents shaded by large plane trees. The scoriae are seen in the greatest quantities in the bed of one of these torrents, below the corner where we descended; but a peasant who has the care of a magazine for the maize, informs me, that towards the summit of the mountain there are heaps of the same substance larger than any near the valley, and shafts of a much greater depth and size. Some of these may be works, perhaps, of the ancient Macedonians, whence a part of the silver money was derived, the prodigious quantity of which is proved by the proportion of it still existing. I am not aware, however, that any ancient author has noticed mines in this part of the country.

On inquiring for ancient buildings, the keeper of the magazine conducts me to the southern angle of the bay, where I find the remains of a thin wall constructed of small stones and mortar, built across the neck of a promontory, and a little within the same point towards the plain, many fragments of ancient pottery on the side of the hill, with a piece of Hellenic wall crossing a little ravine or water-course. In the adjacent angle of the bay is a place called the Skala, where plank and scantling are now lying ready for embarkation. The bay is sheltered by an island in the middle, distant a mile and a half from the shore, and about as much in circumference. It is called Kafkaná (Καυκανάς), a word derived from καυω, like Kafkhió and Kapsa, names which we generally find attached to places preserving appearances of metallurgic operations.

The bay, plain, paleókastro, and skala, are all known by the name of Lybjádha, which the natives derive from that of the mother of Alexander, and not without probability; since the omission of the initial o, the third case, and the conversion of λυμπιάδα into λυμπτζιάδα, are all in the ordinary course of Romaic [demotic Greek] corruption. A situation a little below the serai of the Aga at Kastro, where some fragments of columns are still seen, is said to have been the site of Alexander's mint. Both Turks and Greeks, and even the poorest peasants, are full of the history of Alexander, though it is sometimes strangely disfigured, and not unfrequently Alexander is confounded with Skanderberg.

The port and island of Lybjádha are probably those which in the epitome of the seventh book of Strabo are described as being near Stageirus, and named Caprus, for this is the only island in the Strymonic Gulf, except Leftheridha, and the latter being close to the cape now called Marmari, which forms the northern side of the entrance into the bay of Acanthus, is too far from Stageirus, if that place, as I suspect from the name, stood at the modern Stavros. Leftheridha, moreover, being nothing more than the Romaic form of Eleuthuris, seems to indicate the preservation of an ancient name. Within that cape to the northward there is a small harbour."

William Martin Leake, Travels in Northern Greece Volume 3, Chapter 25, pages 165-167. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

53. Leake and Belon on gold and silver mining in Halkdiki

Leake visited the mineworks at Nizvoro (Stratoniki) and described the crude method by which the ore was placed in furnaces to separate the gold and silver by burning. The heaps of waste ore - slag or scoriae - gave the area the name Sidherokápsa or Sidherokápsika (literally burnt iron), recorded during Byzantine times, as early as 850 AD. The mining areas are still known as Sidirokafsia and Siderokava today. He also mentions that when the shafts were exhausted they were abandoned.

"Belon *, who visited the mines of Sidherokápsa in the middle of the sixteenth century, asserts that he found five or six hundred furnaces in different parts of the mountain, that besides silver, gold was extracted here from pyrites, that 6000 workmen were then employed, and that the mines sometimes returned to the Turkish government a monthly profit of 30,000 ducats of gold. The name Sidherokápsa, although implying a smelting of iron, is generally applied to places where any appearances of metallurgy remain; it is not probable that there ever existed any iron works in this place."

William Martin Leake, Travels in Northern Greece, Volume 3, Chapter 25, page 161. At the Internet Archive.

It is thought that there was a mint at Sidirokafsia as early as the reign of Murad II (reigned 1421-1451). The mines of the area had been reorganized in 1530, during the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (reigned 1494-1566). Among the 6000 workmen at the height of production in the 16th century were Turks, Serbs, Bulgarians, Albanians, Vlachs, Circassians and Sephardic Jews, as well as German technicians.

* Pierre Belon (1517-1564), a French physician and naturalist. He travelled through Greece, Asia Minor, Egypt, Arabia and Palestine 1546-1549, and published Observations, an illustrated account of his journey in 1553.

Les observations de plusieurs singularitez et choses memorables

trouvées en Grèce, Asie, Judée, Egypte, Arabie et autres pays étrangèrs. Paris, 1553. In French, at googlebooks.com.

The descriptions of the mines at "Siderokapsa", Halkidiki are in chapters 50-53. |

Mineral ore from Olympiada. |

| |

Iron pyrites in the ore, from

which gold is extracted.

See also History part 4.

photos: © David John |

| |

|

54. Greek and Macedonian history

We hope to publish more pages about the histories of Greece and Macedonia in the the near future. Meanwhile, you can read a general overview of Macedonian history in our travel guide to Kavala.

See also: A brief history of Pella.

55. Dr. Fotios Petsas

The archaeologist Dr. Fotios Michaelis Petsas (Φώτιος M. Πέτσας, his first name is sometimes written Photios, 1918–2004), who as Curator of Antiquities in Macedonia was involved in the excavation of Pella. He was also a university professor and Director of Antiquities at Delphi. Among his more popular works is an excellent illustrated guide to the archaeological site and museum of Delphi which is still on sale at the museum shop and many other tourist bookstores around Greece.

Professor Photios Petsas, Delphi monuments and museum. 120 pages, with folded colour plan of the site. Krene Editions, Athens, 2008. Price at museum 9 Euros (2013).

Considering his long and distinguished career, it is surprising that there appears to have been very little written about Dr. Petsas, in Greek or any other language, although his name appears in many bibliographies. It seems that he was one of the many archaeologists who lost their posts during the military dictatorship (1967-1974).

If you have any further information about Dr. Petsas, we would love to hear from you.

Please get in contact. |

|

|

Photos, maps and articles: copyright © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: copyright © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide

comprehensive and accurate information across this

website. However, we can take no responsibility for

inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services

mentioned on these pages. |

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|