|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Macedonia > Stageira & Olympiada |

| Stageira & Olympiada |

History of Stageira & Olympiada - Part 3 |

|

|

page 4 |

|

|

| |

Fragments of the lintel of a 6th century BC gate from Stageira (see Ancient Stageira gallery page 30). |

| |

History of Ancient Stageira - Part 3

Establishment, 6th - 5th centuries BC |

| |

Stageira's sister city Akanthos was to become one of the richest and most important cities of northern Greece during the Archaic period, and was particularly famous for its wine. Stageira itself, though far less important economically, appears to have been nontheless quite affluent. The Stageirites certainly had the manpower and money to build substantial fortifications, at least one large temple and an impressive agora (marketplace), and to double the city's area by the early 5th century BC.

The city stood on two low hills which comprise the small headland known as the Liotopi pensinsula. At its greatest extent, in the 5th century BC, the walled city was only 315 metres long and 236 metres at its widest point; 106 metres at its narrowest (see map on Ancient Stageira gallery page 7).

The original settlement was much smaller, occupying only the North Hill, on the tip of the headland. The colonists surrounded their new home with walls, the foundations of which have been discovered by archaeologists beneath later fortifications built during Classical and Byzantine times (see Ancient Stageira gallery pages 30-31).

The remains of a monumental Archaic gateway of the 6th century BC have also been discovered on the south slope of the North Hill. The gate's marble lintel, estimated to have been about 2.5 metres long, was carved with a relief of a large boar (Greek, κάπρος, kapros), the symbol of Stageira, on the left side, facing a lion on the right (see photos and information on Ancient Stageira gallery page 30). The image of a lion attacking a boar is also known from early coins of Stageira (see Olympiada gallery page 2). Part of a 6th century BC inscription was preserved on the lintel, with script chiselled in "boustropheon", i.e. written from left to right and right to left on alternate lines. The surviving fragments of the lintel are now in the Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, while many other finds from Stageira are in the Polygyros Archaeological Museum, in central Halkidiki.

It is not known how much support the early settlers had from Andros and/or Chalcis, or what degree cooperation or competition there was between the colonies. The geographer Strabo wrote that "as Aristotle states..." the leaders of the colonists "were men chosen according to the value of their property, who ruled in an aristocratic manner." (see note in History part 2) It is also known that Aristotle lived the last years of his life in Chalcis, on land he inherited from his mother, who is said to have been descended from one of these leaders. (see note in History part 2) It is likely then, that the leaders could have supported themselves to a certain extent with revenues from their lands in Chalcis.

Around 506 BC Chalcis sided with Sparta and Boeotia in a disastrous war against Athens, and was swiftly and soundly defeated. The Athenians demanded a ransom of two pounds of silver for each prisoner of war, expelled the Chalcidian ruling aristocracy and settled a colony of 4,000 Athenian cleruchs [12] on their land. (See also: Athens Acropolis gallery page 8)

This turn of events must have had an effect on its colonies. Aristocratic colonists may also have lost land and incomes from Chalcis, and could no longer depend on support from kinsmen there. The expelled Chalcidians and their families and households (slaves), may have sought refuge at the colonies, adding to strains in the small settlements.

The Stageirites would certainly be able to live quite well in their new home from agriculture, hunting and fishing. From the narrow wooded coastal plain either side of the Liotopi peninsula the land rises steeply to hills of up to 750 metres high. This land is suitable for the production of olives, wine and other fruits and vegetables, but not for the extensive cultivation of cereals. Today, cereals are still grown on the flatter lands to the north of Halkidiki, on its western side and Pallene peninsula (now called Kassandra), and on the plains of Macedonia. During Classical times, Greece's biggest suppliers of grain were the Greek colonies around the Black Sea. [13]

The settlers will have brought livestock (or stolen it from the natives; cattle has always been a typical form of conquerers' booty), and they had access to fish and hunting prey, which ancient writers tell us was plentiful in this area (e.g. Herodotus: "the coasts of Athos abound in wild beasts..." (see note in History part 4). Wild pigs, roe deer, hares, woodcocks and other birds are still to be found around Halkidiki. Wild boar is hunted today in the Holomontas mountain area west of Stageira, where boar steaks are offered on restaurant menus. [14]

If there is a historical basis to Plutarch's story of the arbitration by the Eretrians, Samians and Parians in the dispute between the Andrians and Chalcidians over Akanthos (see note in History part 2), it may be reasonable to assume that the colonies cooperated with each other to some degree in matters of defence, as well as legal and territorial disputes. It also seems likely that there was some coordination in efforts to establish trade, at least between Stageira and Akanthos. |

Silver drachma of Stageira,

circa 530-520 BC, depicting

a wild boar (kapros). Polygyros Museum. |

| |

Silver incertum depicting

a wild boar, thought to

be from Stageira.

One of several similar coins

in Bode Museum, Berlin. |

| |

Silver tetradrachm of

Stageira, circa 520-500 BC,

depicting a lion attacking

a wild boar. |

| |

Silver tetradrachm of

Akanthos, circa 470-460 BC,

with a lion attacking a bull.

Altes Museum, Berlin. |

| |

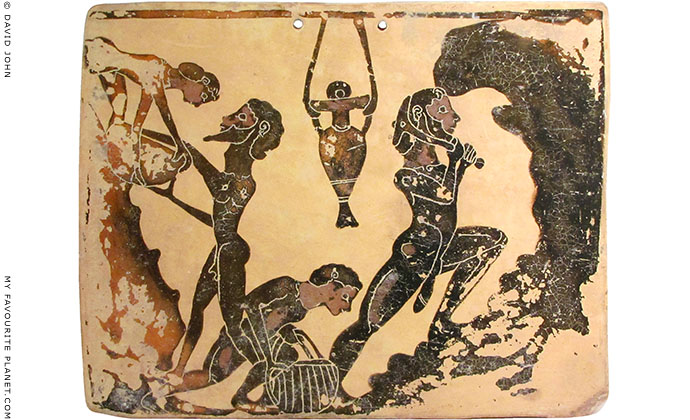

Greek warrior on a pinax

(ceramic plaque) from

Penteskouphia, Corinth

(see below), late

7th - early 6th century BC.

Altes Museum, Berlin. |

| |

| |

Detail of a marble relief depicting a wild boar (Kapros). See Olympiada gallery page 3. |

| |

The east coast of Halkidiki is rich in precious minerals such as gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc and manganese, which have been mined at Stageira and other locations as far south as Akanthos from perhaps as early as the 10th century BC. [15] The tribal peoples who occupied the northern Aegean before the arrival of the Greeks, particularly the Thracians, are known to have worked in precious metals from at least the 4th millenium BC. [16] The Chalcidians may have targeted this area for colonization in order to seize the mineral mines.

Trade in these minerals contributed significantly to the wealth of Stageira and neighbouring settlements. The colonists would have needed the help of experts in the techniques and skills required to mine the ores and extract and purify the minerals, and considerable numbers of labourers, most probably slaves. It is known that the Euboeans mined iron and copper on their island (the name Chalcis means copper), and the control of the mines on the Lelantine plain was one of the causes of conflict between Chalcis and Eretria.

Richly-forested Halikidiki was an important supplier of timber for fuel, construction and ship-building to the more arid and deforested areas around the Aegean. In this trade, it was in competition with the Macedonians, who are thought to have supplied Athens with the timber to build its navy - the famous "wooden walls" of Themistocles, which were to help the Greeks defeat the Persians at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC (see history part 4), and become the dominant naval power in the eastern Mediterranean ( history part 5). [17] The regulation of timber export was later included in treaties between Amyntas III of Macedon (Ἀμύντας Γ΄, ruled 393-370 BC) and the Chalkidian League around 393 and 382 BC. [18]

Stageira's location was advantageous as a port for sea trade between the mainland and the islands and cities of the northern Aegean, and beyond the Hellespont and Sea of Marmara to the Greek colonies around the Black Sea.

As the Persian invaders were to discover to their cost in 492 BC, the conditions around the Athos peninsula could be treacherous ( see next page), and many ships' captains sailing from the east would have preferred to put in at a port on the eastern side of Halkidiki. Akanthos and its port at Sane profited far more from this situation than Stageira, but the latter seems to have done quite well. Its harbour, Kapros, was on a wide bay, today the beach of Olympiada village, which would have provided good a anchorage and landing place for trading ships. There are also several other smaller bays to the southeast of the Liotopi peninsula. |

Mineral ore from Olympiada |

| |

Iron pyrites in the ore,

from which gold is extracted.

See also History part 7. |

| |

Coin of Amyntas III

of Macedon

(ruled 393-370 BC).

Pella Archaeological Museum.

photos: © David John |

| |

| |

Corinthian ceramic plaque (pinax) depicting workers in a quarry. 630-610 BC.

This is one of the oldest known depictions of men working in a quarry, probably a clay pit.

From Penteskouphia, Corinth. Now in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin. [19]

|

"In the earth itself you often see sulphur generated and bitumen congealing with its vile stink. When men are following veins of gold and silver, groping with their picks in the bowels of the earth, what fumes are emitted from the pits of Scapte Hyle!

What malignant breath is exhaled by gold mines! How it acts upon men's features and complexions! Have you not seen or heard how speedily men die and how their vital forces fail when they are driven by dire necessity to endure such work? All these vapours, then, are given off by the earth and blown out into the open, into the unconfined spaces of the air."

Lucretius (99-55 BC), On the Nature of the Universe, Book VI Meteorology and Geology, 74-76. [20] |

|

|

| |

Stageira &

Olympiada

History

part 3 |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

12. Athenian cleruchs

A cleruchy (Greek, κληρουχία, kleroukhia) was a special type of Athenian colony, set up as an extension of the city-state rather than a separate entity (apoikia or emporion), and populated by cleruchs (κληροῦχος, klerouchos, lot-holder; plural κληροῦχοι, klerouchoi), usually landless Athenian citizens appointed a plot of farmland (κληρος, kleros) in foreign territory. Cleruchs retained their Athenian citizenship and affiliation to their demes (tribes), paid taxes and were liable for military service. As landowners, cleruchs were raised to the social status of Zeugitae (ζευγῖται, from ζευγος, zeugos, yoke, or ζευγον, zygon, member of the phalanx), the third highest of four census divisions according to Solon's 594 BC constitutional reforms, who served as hoplites in the Athenian army.

This system of colonization is thought to have been first employed by Athens and Megara on the island of Salamis during the 6th century BC.

Because of the military as well as economic importance of these colonies, cleruchs were not allowed to sell or lease their land, except under special circumstances, so that effectively they formed an occupying army. |

|

|

| |

Farmland south of Lake Bolbi, near the site of ancient Apollonia, north of Stageira. |

| |

13. Grain to Greece

In the west, the Greek colonies of Sicily also produced enormous amounts of grain. Supplies from Egypt became more important to the economy of the Mediterranean during Roman times.

14. Halkidiki wildlife

Wild animals around Halkidiki include: wild pigs, roe deer, hares, red foxes, wild cats, martens, badgers, weasels, lizards, tortoises, woodcocks and several species of birds, including birds of prey. Monk seals are also still to be found around the Athos peninsula.

See:

anotherhalkidiki.com/en/etap.html, alternative tourism in Halkidiki.

Eleni Voultsiadou and Apostolos Tatolas, The fauna of Greece and adjacent areas in the Age of Homer: evidence from the first written documents of Greek literature. Journal of Biogeography (2005), 32, 1875-1882. Department of Zoology, School of Biology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece.

15. The mineral wealth of Stageira and east Halkidiki

Mining activity here reached its height under Philip II and Alexander the Great, and continued during the Ottoman period. Controversially, industrial mining has recently resumed around Olympiada and Stratoni.

See:

Municipality of Aristotle: Mines. History of mining in east Halkidiki, at stagira.gr.

Stratoniki (Village), Chalkidiki: The mines and their history, at Greek Travel Pages (GTP).

Stratoni mine, at the website of Eldorado Gold Corporation.

Marianna Dági, Goldsmith's craft in late Classical and early Hellenistic Macedonia - Derveni, Sedes, Stavroupolis (PDF document). PhD thesis. Eötvös Loránd University of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary, 2011.

Kerin Hope, Greece’s Eldorado (PDF document), An article about the Canadian company Eldorado Gold's plans to reopen the mines around Olympiada. Businessfile magazine, No. 84, January - March 2012. At economia.gr.

M. Vavelidis, V. Melfos, Study of the ancient metallurgical works in Kipouristra, Olympiada (Ancient Stageira), NE Chalkidiki. Scientific Annals of the Faculty of Geology, School of Science, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Special Volume 101, 2012, pages 9-16 (in Greek).

In September-November 1999, Dr. Kostas Sismanidis of the Greek Archaeological Service was able to make a brief investigation of the site of the ancient mines of Stageira, 2 km west of Olympiada, before the controversial planned resumption of modern industrial mining. He discovered remains of Early Iron Age (10th century BC) settlements and buildings. (See also History part 6.)

Source: Nikos Axarlis, Gold and Aristotle. Archaeology magazine, December 17, 2001. Archaeological Institute of America.

16. Thracian gold

Examples of Thracian work in precious metals have been dated to as early as 3200 BC. See, for example:

Gold der Thraker: archäologische Schätze aus Bulgarien (Gold of the Thracians: archaeological treasures from Bulgaria). Catalogue of the 1980 exhibition tour in Germany. Römisch-Germanisches Museum Köln and the Bulgarian Committee for Culture. Published by Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein, Germany, 1979. |

|

|

|

17. Halkidiki and Macedonia as suppliers of timber

"See Hicks, 74, for a treaty between Amyntas and the Chalcidians, B.C. 390-389: 'The article of the treaty between Amyntas III, father of Philip, and the Chalcidians, about timber, etc., reminds us that South Macedonia, the Chalcidic peninsula, and Amphipolis were the chief sources whence Athens derived timber for her dockyards.'

Thuc. iv. 108; Diod. xx. 46; Boeckh, 'P. E. A.' p.250; and for a treaty between Athens and Amyntas, B.C. 382, see Hicks, 77; Kohler, 'C.I.A.' ii. 397, 423."

Henry Graham Dakyns (1838-1911), in the notes to his translation of Hellenica by Xenophon.

Xenophon, Hellenica, Book V. Translated by H. G. Dakyns. At Project Gutenberg.

See also:

Russell Meiggs (1902-1989), Trees and timber in the ancient Mediterranean world. Monograph. Oxford University Press, 1982.

Eugene N. Borza, Timber and Politics in the Ancient World: Macedon and the Greeks. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 131, No. 1 (March, 1987), pages 32-52. At jstor.org.

K. J. W. Oosthoek, The role of wood in world history. Environmental History Resources at eh-resources.org.

Timber as a Trade Resource of the Black Sea by Lise Hannestad, Department of History, Pennsylvania State University. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 131, No. 1, 1987.

"Moreover, there are a thousand other uses for those trees which are indispensable for carrying on life. We use a tree to furrow the seas and to bring the lands nearer together, we use a tree for building houses; even the images of the deities were made from trees..."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 12, chapter 2. Translated by H. Rackham, W. H. S. Jones, D. E. Eichholz.

Published in 10 volumes by Harvard University Press, Massachusetts and William Heinemann, London, 1949-54.

The entire work on one web-page, with a good clear layout, at Jon Lange's fascinating masseiana.org.

See also Pliny's mention of a remarkable white poplar tree in Stageira on Ancient Stageira gallery page 34. |

|

Stater of Amyntas III of Macedonia.

393 - 370/369 BC.

Bode Museum, Berlin. |

|

|

18. Treaties between Amyntas III and Halkidiki

An inscription proclaiming a 50-year peace treaty between Amyntas III (ruled 393-370 BC) and Halkidiki, dated to circa 393/392 BC, was found in Olynthos. See:

Meletemata 22, Epig. App. 1 - Tod, GHI 111 (in Greek), at The Packard Humanities Institute, epigraphy.packhum.org.

Marcus Niebuhr Tod (1878-1974), A Selection of Greek Historical Inscriptions, Volume II: From 403 to 323 BC. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1948.

P. J. Rhodes, Robin Osborne, Greek Historical Inscriptions, 404-323 BC, No. 12 (with translation). Oxford University Press, 2004.

19. Penteskouphia Pinakes

Corinthian ceramic plaque (pinax), black-figure painted ceramic.

630-610 BC (Late Proto-Corinthian - Early Corinthian).

Height 10.4 cm; width 13.2 cm

Antikensammlung, Berlin State Museums (SMB). Inv. No. F 871B.

In the ancient Greek world, a pinax (πίναξ, literally board; plural πίνακες, pinakes) was a plaque (or tablet) of painted wood,

moulded and/or painted ceramic, inscribed marble or cast bronze, placed as a votive offering in a temple, sanctuary or tomb. Some pinakes were inscribed wax tablets or painted cloth. The subject of the pinakes was usually one or more deities, standing or enthroned (sometimes represented only by their symbols), often shown being approached by worshippers carrying sacrifices. The term eventually came to denote a painting, and a pinakotheke a picture gallery (as in the "Pinakotheke" of the Propylaia of the Athens Acropolis).

The first Penteskouphia Pinakes were a chance find in early 1879 by a farmer, who discovered around a thousand painted terracotta pinakes made as votive offerings to Poseidon and Amphitrite at Penteskouphia, 2.5 km southwest of ancient Corinth, near the ruins of a hilltop Frankish fortress. Since many of the pinakes bear inscriptions and show various stages of pottery production, it has been concluded that they were offerings of the potters themselves, and that the above scene shows workers digging clay from a pit.

Most of the Penteskouphia Pinakes are just fragments, painted on one or both sides, and it seems that at some point in history they were broken when they were removed from the temple of Poseidon and dumped in a hillside ravine. Scholars do not feel it worth mentioning the name of the farmer who discovered the enormous hoard, or how most of them found their way to Berlin, and another 16 to the Louvre in Paris; vague references are made to "illicit" trade.

A. Milchhöfer investigated the site at Penteskouphia a year after the initial find. Archaeologists from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens located the site again in 1905, and during a brief excavation found another three hundred fragments of pinakes, which are now in the Corinth Museum. See the report by O. M. Washburn in: The Journal of the Archaeological Institute of America, Volume X, 1906, pages 19-20, Excavations at Corinth in 1905. Macmillan, London and New York. At the Internet Archive.

Adolf Furtwängler (1853-1907), the German archaeologist and assistant director at the Royal Antiquarium of Berlin, included a study of the pinakes in his catalogue of the ancient ceramics collection in the museum: Beschreibung der Vasensammlung im Antiquarium,

Band I, A.IX. Altkorinthische Gattung, pages 47-132 (in German). W. Spemann, Berlin, 1885. At the Internet Archive.

In 1891 The German Imperial Archaeological Institute published black and white drawings of some of the pinakes with brief decriptions: Antike Denkmäler Band 1, pages 3-4 and plates 7 and 8. Kaiserlich Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1891. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

A study of the Penteskouphia Pinakes is currently been written by Dr. Eleni Hasaki, Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Arizona, under the title The Penteskouphia Pinakes and Potters at Work at Ancient Corinth. See: anthropology.arizona.edu/hasakie. Dr. Hasaki has neatly described the potters' works as "a visual compendium of their daily life in ceramic workshops". |

|

|

|

20. Lucretius on goldmines

Titus Lucretius Carus (circa 99-55 BC), also known simply as Lucretius, was a Roman poet and philosopher about whose life little is known. His only known work, De rerum natura, an epic philosophical poem about Epicurean philosophy, known in English as On the nature of things or On the nature of the universe, was highly praised by other ancient authors, including Cicero, Ovid and Vitruvius.

His mention of "the pits of Scapte Hyle", is a reference to the gold mines near ancient Neapolis (today Kavala, Macedonia). Herodotus wrote that he had visited the mines at Scapte Hyle (Greek, Σκαπτὴ Ὕλη or Σκαπτηςύλη; Latin, Scaptensula), and that they produced substantial wealth for the island of Thasos at the time of the first Persian invasion by Darius I (see History of Stageira & Olympiada part 4). Herodotus, The Histories, Book 6, chapters 46-47.

Around 465 BC the Thasians revolted against the Delian League but were defeated by Athens, which confiscated their possessions on the mainland. Later some of the mines were owned by the Athenian general and historian Thucydides (see note 25 in History part 5).

Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe, Book VI Meteorology and Geology. Translated by R. E. Latham, 1951. At american-buddha.com

Another English translation (rather old-fashioned), by William Ellery Leonard. E. P. Dutton, 1916:

Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, Book VI, lines 769-817, at Perseus Digital Library.

Titus Lucretius Carus, On the Nature of Things, complete, on a single web-page at Project Gutenberg. |

|

|

Photos, maps and articles: copyright © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: copyright © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide

comprehensive and accurate information across this

website. However, we can take no responsibility for

inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services

mentioned on these pages. |

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|