|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Macedonia > Kavala |

| Kavala, Greece |

History of Kavala |

|

page 2 |

|

|

| |

Kavala's main harbour and city centre from the Kastro. |

| |

| A brief history of Kavala |

| |

| The ancient city of Neapolis (Νεάπολις, New City) became known as Christoupolis under the Byzantine Empire and then Kavala during the Ottoman period. The original name became lost over the centuries, and few traces of its pre-Christian past remained visible by the 17th century, when scholars attempted to identify its location. [1] The confirmation that modern Kavala stands on the site of ancient Neapolis was first gained following excavations by the Greek archaeologists Georgios Bakalakis and Dimitris Lazarides in the 1930s and 1950s. |

|

|

| Prehistory and the Thracians |

Evidence of human occupation in the areas now known as Macedonia and Thrace reaches back to the Palaeolithic Period, and the settlement of Dikili Tash, northwest of Kavala, has been dated to the Late Neolithic Period (5500-4200 BC), continuing into the Bronze Age (3000-1050 BC) until the early Iron Age (1050-700 BC).

From at least the Bronze Age Thracian tribes occupied much of the land north of Thessaly, east of Illyria (modern Albania) to the Bosphorus (modern Istanbul), and as far north as the Black Sea and the Danube (modern Bulgaria). They were in constant competition with Celts, Macedonians and Scythians.

The earliest written accounts of the Thracians appeared in Homer's Iliad, in which they fought on the side of the Trojans against the Greeks.

The first large wave of Greek conquest and colonization around 1000 BC concentrated on Anatolia (Asia Minor) and the foundation of cities such as Miletus and Ephesus.

During the second wave in the 8th - 6th centuries BC Greeks from islands such as Euboea, Andros and Paros turned their attentions to Thrace. Gradually the Thracians around the coast from Halkidiki to the Black Sea were supplanted by Greek colonies, although it is thought that in some places Greeks and Thracians coexisted peacefully. However, this area was still referred to as Thrace by later Greek and Roman authors and in offical documents and inscriptions. |

|

Head of a terracotta figurine

from the prehistoric settlement

at Dikili Tash (Philippi).

Kavala Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Foundation of Neapolis

7th century BC |

|

|

|

Around 680 BC Greeks from Paros founded a colony on Thasos, which was formerly a Phoenician colony. From Thasos the Parians founded or took control of several settlements on the mainland, and the new colonies became collectively known as the Thasian Peraia. [2]

The city now known as Kavala was named (or renamed) by the Thasian-Parians Neapolis (Νεάπολις, New City) and provided them with a port serving their commercial and military interests on the mainland.

They also colonized Krinides (Κρηνίδες, later Philippi, see below), 17 km inland, and took control of rich gold and silver mines at Scapte Hyle (Σκαπτὴ Ὕλη, a forest that may be dug) around Mount Pangaion, not far from Neapolis.

The Greek historian Herodotus (circa 484 - circa 425 BC) tells us that at the beginning of the 5th century BC Thasos earned an average of 80 talents a year from these mines.

They used much of this wealth to fortify their cities and build warships. At some time during the 5th century BC Neapolis was fortified with walls of local granite, and a fortress was built on the acropolis on the steep, rocky headland now occupied by the Panagia district.

Neapolis began minting its own coins around the last quarter of the 6th century BC. This has led many scholars to believe that the city may have become independent of Thasos around this time, although there appears to be little other evidence for this. If Neapolis was independent, did the Thasians still use its port to communicate with its other mainland territories, and what part did the city play in the mining business?

The coins of Neapolis had the Gorgoneion, the head of the the Gorgon Medusa, on the obverse side, and later coins, from the 5th - mid 4th century, showed the head of a woman on the reverse. This is thought to be either Athena, Artemis or a nymph (see photos below). A sanctuary and temple of the city's patron goddess Parthenos (Παρθένος, Virgin) stood in the area now occupied by the Imaret. |

|

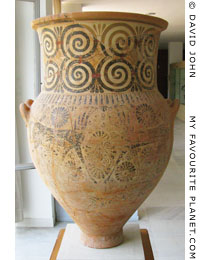

7th century BC Melian amphora.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Silver stater coin of Neapolis.

510-490 BC.

Obverse: Gorgon's head.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Four silver hemidrachm coins (half drachmas) of Neapolis (photos all to the same

scale). On the obverse side is a Gorgoneion, the head of the the Gorgon Medusa.

On the reverse the head of a woman facing right, probably the city's patron goddess

Parthenos (Παρθένος, Virgin). Above her head are the letters Ν Ε, and below Π Ο,

an abbreviation for Neapolitans. This type of coin was minted in four groups from

422 to 340 BC, after which Macedonian coinage took over.

From of a hoard of silver coins found at Potami (Ποταμοί), East Macedonia,

northern Greece (around 40 km north of Drama). Classical period.

During the Archaic and Classical periods (6th - late 4th centuries BC) the most

common coins in circulation in this part of Aegean Thrace were those of Thasos

and Neapolis, usually in smaller denominations, particularly Thasian hemihekta

(half of a sixth of a stater) and Neapolitan hemidrachms.

The Potami hoard included 340 hemidrachms of Neapolis, 462 hemihekta of Thasos

as well as 58 silver tetradrachms (four drachmas) of King Philip II of Macedonia.

Drama Archaeological Museum, East Macedonia, Greece. |

|

| |

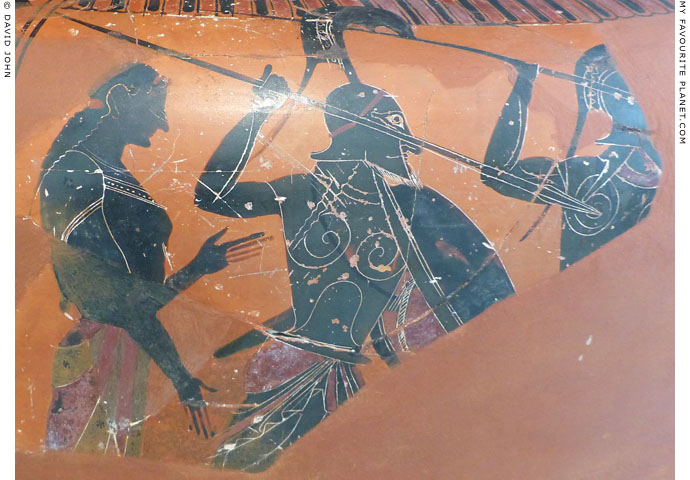

Detail of an Attic black figure column krater depicting warriors, 530-520 BC.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. |

| |

|

|

|

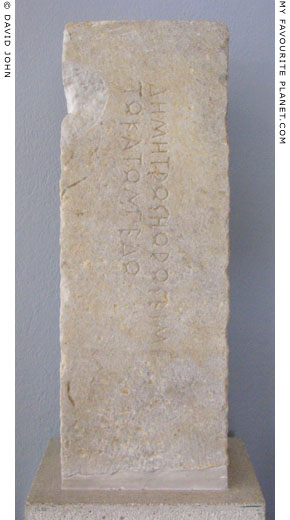

Two horoi (boundary markers) from a sanctuary of Demeter Hekatompedos in

ancient Galepsos (Γαληψός, on the coast, 55 km west of Kavala), end of the 6th

to the beginning of the 5th century BC. Like Neapolis, Galepsos was a colony

of the Thasian-Parians, and the inscriptions are written in the Parian alphabet.

Δήμητρως ℎώρως εἰμὶ

τὠ κατωνπέδω

Inscription SEG 43 400.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. Invoice numbers Λ1202 and Λ1203. |

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Persians and Athenians

6th - 5th centuries BC |

|

|

|

In 514-513 BC Megabazos, a general of the Persian King Darius I, conquered Thrace. Persian control lapsed during the Ionian Revolt by the Greeks of Asia (499-494 BC), but Darius sent an another expedition under his son-in-law Mardonius to conquer Thrace and Macedonia in 492 BC.

Although Darius' plan to conquer Greece was thwarted by his defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, Thrace and Macedonia remained in Persian hands. His successor Xerxes I gathered an even larger army and navy and launched his attack on Greece from Thrace and Macedonia in 480 BC, but was defeated at the Battle of Salamis, and again a year later at the Battle of Plataea (see History of Stageira part 4).

Eventually the Greek forces were able to drive the Persians out of Thrace and Macedonia. Around 477 BC Athens and other Greek states formed a military alliance, known to modern historians as the Delian League, to protect the freed Greek cities from the Persians. The members, which included Thasos and Neapolis, were obliged to support the league's campaigns by paying a tribute or quota fixed for each city, either in cash or by providing a certain number of ships.

The oldest written mention of the name Neapolis, as Neapolis in Thrace (Νεάπολις εν Θράκει, Neapolis en Thrakei) to distinguish it from several other cities with the same name (for example in Halkidiki and on the Hellespont), first appeared in 454/453 BC on a tribute list (or quota list) of the Delian League, tall marble steles set up on the Athenian Acropolis that listed the member cities and how much each was pledged to pay. In the list of the following year it was referred to as Neapolis near Antisaron (Νεάπολις παρ’ Αντισάραν, Neapolis par Antisaron), due to its proximity to the neighbouring settlement of Antisara (Αντισάρα, about 8 km west of Kavala), and on other lists simply as Neapolis or Neopolitans (see History of Stageira part 5).

The tribute lists show that Neapolis paid 1000 drachmes a year to Athens until 429/428 BC, except for 450/449 BC when it only paid 500 drachmes.

When, around 465 BC, Thasos rebelled against the conditions set by the league, it was attacked, besieged and defeated by Athens. The Thasians were forced to demolish their city walls, pay an increased sum to the league's fund and hand over their ships and their lands on the mainland, including the gold mines.

The Athenian historian Thucydides (Θουκυδίδης, Thoukydides, circa 460-395 BC) inherited the rights to mine the gold at Scapte Hyle, and after his banishment from Athens he retired here to finish his work The history of the Peloponnesian War.

Neapolis supported Athens in putting down the Thasian rebellion, for which it was honoured by decrees placed on the Athenian Acropolis in 410/409 BC (see photo below). |

King Darius I of Persia kills

a rebel with his lance.

Drawing by Faucher-Gudin,

from an impression of an

intaglio in Saint Petersburg. |

| |

A silver stater coin of Neapolis

with a Gorgoneion, the head of

the Gorgon Medusa. 500-480 BC.

Bode Museum, Berlin. |

| |

| |

Ionic capital from the temple of Parthenos (Παρθένος, Virgin), the patron deity of ancient Neapolis.

The sanctuary of the goddess was on the west side of the Panagia peninsula, near to where

the Imaret now stands. The oldest pottery finds indicates that Parthenos was worshipped here

from at least the 7th century BC, the time of the city's foundation. The peripteral Ionic temple, built

of Thasian marble in the early 5th century BC, is thought to have replaced a smaller Archaic temple.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. |

| |

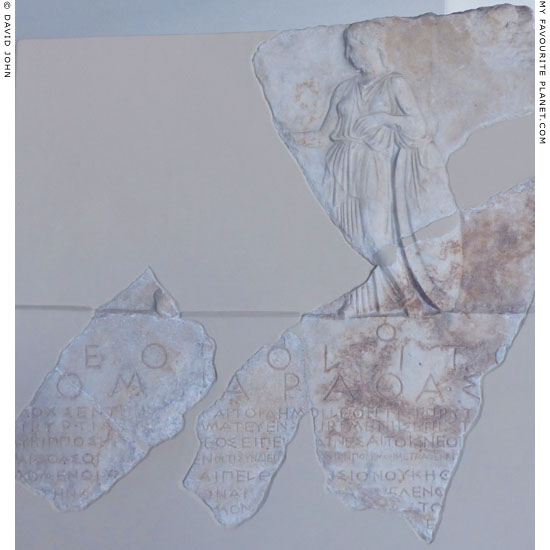

Fragments of a stele from the Athenian Acropolis, dated 410/409 BC,

with decrees concerning Neapolis. The decrees honour Neapolis for

its continuous commitment to Athens and its support in the war against

the rebels of Thasos. In the relief, Athena, resting on her shield stretches

out her hand, probably to Parthenos, the patron goddess of Neapolis.

The Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6598.

(Formerly in the Epigraphical Museum, Athens.) |

| |

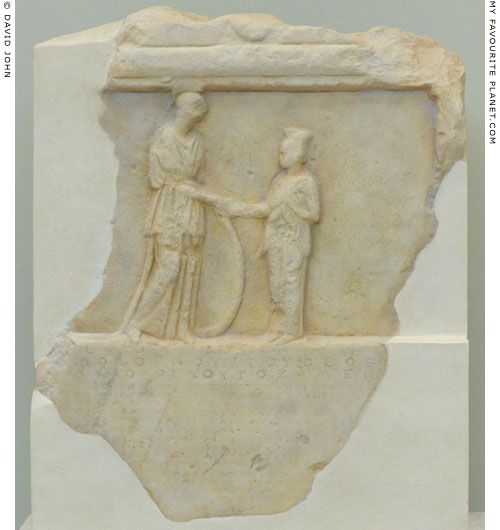

A fragment of a marble stele dated to 356/355 BC, during the archonship

of Elpinos, with an Athenian decree honouring the citizens of Neapolis.

|

The relief shows Athena (left, holding a shield) shaking hands with Parthenos, the patron goddess of Neapolis. The inscription of the decree below mentions two ambassadors from Neapolis to Athens: Demosthenes, son of Theoxenos, and Dioskourides, son of Amipsios.

The relative status of the two cities is evident from the fact that the figure of Parthenos is smaller than the Athenian patron deity.

Cast in Kavala Archaeological Museum, from the original in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 1480. Inscription IG II(2) 128. Unknown provenance. Hymettian marble. Height 52 cm (relief 24.5 cm), width 39 cm. |

|

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Philip and Alexander

4th century BC |

|

|

|

In 356 BC Philip II of Macedonia (382-336 BC) took the nearby city of Krinides (Κρηνἱδες, Fountains) and renamed it Philippi (Φίλιπποι, Philippoi). With a new center of operations in eastern Macedonia he conquered Thrace in 346 BC and Thasos in 340 BC. He also gained control of the gold and silver mines of Mount Pangaion (Παγγαίο όρος), which enabled him to set up a mint and finance his further ambitions (see Big Money at The Cheshire Cat Blog).

Neapolis lost its autonomy and was relegated to being the port of Philippi, which became the most important city in the area and the location of the local Macedonian mint. Although Neapolis almost ceased minting its own coins, it did produce a new series of bronze coins during the Hellenistic period. The sanctuary of Parthenos continued to receive offerings from all around the Hellenistic world, and the city was mentioned in several inscriptions and resolutions in places such as Delphi and Kos.

Philip's son, Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) continued his father's military expansion on a much grander scale. He conquered Greece's ancient enemy Persia and went on to conquer most of the known world to the east and south of the Mediterranean. This was Macedonia's finest hour, and great riches poured into the country. Presumably, Neapolis must have benefited from this brief period of glory.

But Alexander's concentration on his foreign adventures would lead to the end of Macedonian power forever. There was no automatic law of royal succession in Macedonia, as it was the custom for kings to choose their favourite son. And since Macedonians were also polygamous, they often had a wide choice.

So when Alexander died in Babylon in 323 BC without naming a successor, his relatives and generals (the Diadochoi, successors) began a series of long and bloody power struggles. It was not only his empire which fell apart: The unity of Macedonia, built with blood, sweat and tears by several generations of kings, also disintegrated, and their military might which protected and held Greece together went downhill fast. |

|

Gold stater of Philip II of Macedon.

circa 323/2 - circa 315 BC.

Obverse side: laureate head of

Apollo in profile, facing right. |

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Roman Empire

2nd century BC - 2nd century AD |

|

|

|

As the Roman Empire spread eastwards, the Macedonians were still proving very troublesome. Rome had to defeat Macedonia to acquire Greece, which it did in 196 BC, although it did not completely conquer it until 168 BC.

Initially, Rome divided Macedonia into four subject, self-governing republics or cantons (Greek, μερίδες, merides; Latin, regiones), but around 148-146 BC it became a single Roman province, Provincia Macedonia (Greek, Ἐπαρχία Μακεδονίας, Eparchia Makedonias), with Thessaloniki as its capital.

Neapolis became an important station along the Via Egnatia, the military and commercial road built by the Romans between between the Adriatic in the west to Byzantium in the east, Greece's first superhighway. A 2 kilometre stretch of the Via Egnatia can still be seen at Kavala, see page 5, Activities and sightseeing in Kavala.

Brutus and Cassius, two of Julius Caesar's assassins, based their fleet here before the Battle of Philippi against Mark Antony and Octavian in 42 BC. The former were defeated, which sealed the end of the Roman Republic as Octavian soon after became the first emperor, known to us as Emperor Augustus. |

|

Silver coin of Emperor Antoninus Pius

(reigned 138-161 AD), from a hoard of

55 Roman silver coins of 150-250 AD

found in the foundations of a building

in Kavala.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

Funerary relief depicting members of a family.

Roman period, early 2nd century AD.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. L 779. |

| |

History

of Kavala |

Saint Paul and Christianity arrive

around 49 AD |

|

|

|

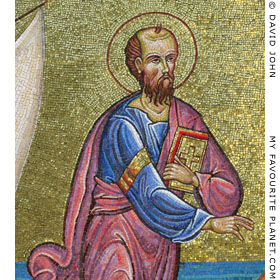

Exit Brutus. Enter Chrisitanity. Around 49 AD Saint Paul the Apostle made his first landing on the European mainland on his way from Troy to found the Christian church in Philippi.

Book of Acts chapter 16, verses 8-12:

"And passing by Mysia, they came down to Troas.

A vision appeared to Paul in the night: a man of Macedonia was standing and appealing to him, and saying, 'Come over to Macedonia and help us'.

When he had seen the vision, immediately we sought to go into Macedonia, concluding that God had called us to preach the gospel to them.

So putting out to sea from Troas, we ran a straight course to Samothrace, and on the day following to Neapolis and from there to Philippi, which is a leading city of the district of Macedonia, a Roman colony; and we were staying in this city for some days."

Many Christians consider Paul's arrival here as an important historical event and a vital step in the spread of Christianity to Europe. Religious tourists visit Kavala and Philippi, as well as Thessaloniki and Veria where he also preached, and part of many itineraries is a visit to Kavala's short stretch of the Via Egnatia, along which the apostle and his companions walked from Neapolis to Philippi. |

|

The arrival of Saint Paul in Neapolis.

Mosaic at the Apostle Paul Monument,

Kavala. |

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Barbarians and Byzantines

2nd century AD - 1387 |

|

|

|

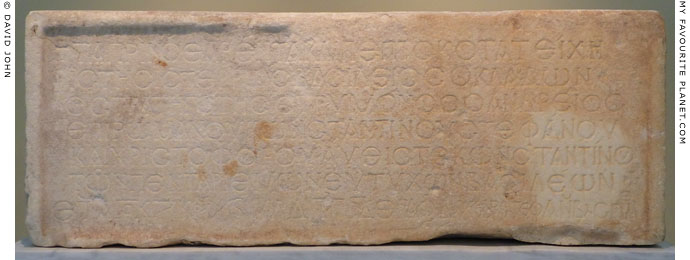

Inscription on a marble cornerstone from the Byzantine city wall of Christoupolis

recording the rebuilding of the walls in 925/926 AD by Basileios Kladon, the

strategos (general) of the Strymon district. Length 120 cm, height 50 cm.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 66.

|

The Roman Empire declined and fell (a process which began in 180 AD according to Gibbon), and its successor the Byzantine Empire failed to keep a tight grip on its territories. Waves of invaders swept through Macedonia: Goths, Huns, Normans, Franks, Bulgarians, Serbians, Turks, Venetians... Again and again the inhabitants of the city had to take refuge within the fortifications of Panagia's acropolis, later known as the Kastro. Again and again the city and the fortifications had to be rebuilt.

Neapolis was mentioned as a city in the Byzantine eparchia (ἐπαρχία, administrative region) of Macedonia in the Synekdemos (Συνέκδημος), a 6th century collection of tables listing administrative divisions and cities of the Byzantine Empire. [3] The Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea (circa 500-565 AD) mentioned Neapolis among the places in Macedonia at which the fortifications were restored by Emperor Justinian I (reigned 527-565 AD). [4]

During the 8th-9th century, as part of the Byzantine Empire, the city became known as Christoupolis (Χριστούπολις, City of Christ) in commemoration of Saint Paul's visit. It was part of the Byzantine theme or district of Strymon (θέμα Στρυμόνος, Thema Strymonos), with its capital at Serres.

The inscription above records the rebuilding of the city's fortifications by Basileios Kladon (Βασίλειος ό Κλάδον), the strategos (general) of the theme, in 925/926 AD. It mentions that Kladon rebuilt the walls which had collapsed or been destroyed, in "the year 6434 since the creation of the world", during the reigns of "the five happy emperors", the co-emperors Romanos (Ρωμανός Α΄ Λακαπηνός, Romanos I Lekapenos), his three sons Konstantinos, Stephanos and Christophoros and the legitimate heir to the throne Constantine (Κωνσταντῖνος Ζʹ, Konstantinos VII). [5] |

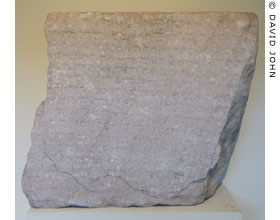

|

Part of a marble plinth from the

Byzantine city wall of Christoupolis

inscribed with a summary of the

final years of the Kommenian

dynasty. The inscription mentions

the destruction of a church by

fire circa 1182-1185, the period

of Norman raids in the area,

and its reconstruction in 1193.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Ottoman Turkish occupation

1387-1913 |

|

|

|

| Finally, around 1387 (some historians believe as early as 1383), during the reign of Ottoman Sultan Murad I (1362-1389), Christoupolis was taken over by the Turks and once more the city was destroyed. When the Venetians besieged and took the city in 1425, they weren't able to hold it long; the Turks returned, laid siege and were back in charge within a month. This suggests that either the defenders were useless, or that the fortifications and local infrastructure had been so badly damaged that the place was indefensible. |

|

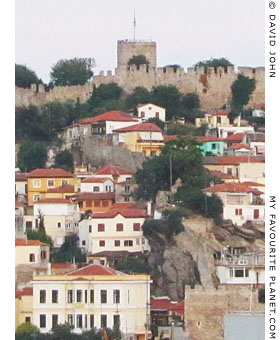

Kavala's Kastro above the old houses

of the Panagia district. |

| |

Rebuilding, 15th-16th century

Over the next 100 years the city was slowly repopulated by Greeks and Turks. Following the conquest of Hungary by Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent (reigned 1520-1566) in 1526 a number of Jews living in the newly conquered territory were resettled here.

Around 1530, major rebuilding work was started, including a complete restructuring of the fortress and city fortifications. An aqueduct was built to the west of Panagia, apparently to replace an earlier aqueduct which had been ruined during the 14th century. Fed by a nearby spring, the new aqueduct was based on a Roman-style design and became known as the Kamares (Οι Καμάρες, the Arches).

By the end of the 16th century the city had become known as Kavala. There continues to be much conjecture about the origin of this name, but none of the theories seems totally convincing. |

|

The Kamares aqueduct, Kavala.

Read a description of the Kamares

on the Sightseeing in Kavala page.

See more photos of the aqueduct

on gallery page 12. |

| |

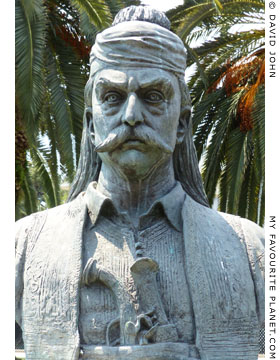

Mehmet Ali, 1769-1849

Kavalans are proud to claim Mehmet Ali (also known as Mohammed Ali, 1769-1849), Pasha of Egypt as a native son. [6] This may come as a surprise to those who know of his ruthless political career, especially his role in attempting to crush Greece's struggle for independence from Turkey.

Mehmet Ali was the son of an Albanian farmer and lived in Kavala for many years. He was accepted by Kavalans as one of theirs, and is still hailed as a great benefactor of the city.

(Some sources state that he born in Cavajo in Albania, which is the cause of some confusion, probably itself caused by confusion of place-names and Mehmet Ali's ethnicity.)

He joined the Turkish army and was ambitious, scheming and ruthless in his swift rise to the top. After leading an Albanian contingent sent by the Turkish sultan to help drive Napoleon's armies out of Egypt, he manoeuvred himself into the position of Pasha (viceroy) of Egypt in 1805. He waged bloody military campaigns in the Middle East, North Africa and Greece, ostensibly to put down the enemies of the sultan, but he steadily increased his own political power and influence. In 1831 he threatened the Turkish Empire itself by seizing Syria. It took the combined powers of Britain, Russia, Austria and Prussia to dislodge his forces.

He was eventually not only forgiven by the sultanate but his pashalic was made hereditary. Thus began the final Egyptian dynasty which ended with the last reigning monarch King Farouk (1920-1965), who abdicated in 1952 after a military coup which led to the foundation of the modern Republic of Egypt.

But for all this, Kavala is so proud of Mehmet Ali that they erected a magnificent equestrian statue of him in 1949 outside his family home, which they have meticuously preserved.

Read a description of the House of Mehmet Ali

in Kavala on the Sightseeing in Kavala page.

See larger photos of the house and

the statue on gallery pages 21-22. |

|

The House of Mehmet Ali in Kavala,

built around 1780-1790. |

| |

The statue of Mehmet Ali in Kavala. |

| |

| |

Inscribed marble gravestones from the 18th - 20th centuries from Kavala cemeteries.

Kavala Archaeological Museum.

|

Left: A Muslim gravestone topped with a turban, with a simple inscription commemorating Ahmed Beşe (Beşe, pronounced Beshé, was a military title without specific rank or function) who died in year 1196 AH of the Muslim calendar (1781-1782). The inscription in Ottoman calligraphic lettering states:

"[Recite] the Fatiha for Ahmed Beşe,

who has been admitted to God's mercy and

whose sin has been forgiven,

who died at the appointed time of god's decree

in the year 1196."

Centre: A Christian funeral stele with reliefs of an angel (or cherub), a skull and crossed bones and a flower with a broken stem. Either side of the skull are the initials of the deceased's name "E" and "Σ".

Right: A tombstone from the Jewish cemetery of Kavala, with an inscription for a woman named Esterina Fransez who died in the year 5694 of the Jewish calendar (1934). The inscription is in Ladino, the language of Spanish Jews who fled from the Inquisition and settled in the Ottoman Empire, apart from the first and last lines which are abbreviations of stock tombstone phrases in Hebrew.

"B[lessed is the] T[rue] J[udge]

Here lie the

mortal remains

of the deceased

Ersterina Fransez

died on 18 Shevat 5694

M[ay her] s[oul be] b[ound up in the bond of

everlasting] l[ife]." |

|

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

The Imaret |

|

|

|

Another of the city's attractions is the Imaret, which Mehmet Ali had built in 1817, on the west side of the peninsula, on the street leading to his house, and near the site of the ancient sanctuary of Parthenos (see above). An elegant, long, low series of buildings crowned by domes and chimneys, its facade is a long, plain wall punctuated by entrance halls decorated with inscriptions in Arabic script. (Turkish has only been written in the Latin script since Atatürk began his reforms in the 1920s and had the entire vocabulary transcribed acccording to the German phonetic model.) Its function was as a hostel for students of the Medressa (Muslim seminary) a few hundred metres away, as well as an almshouse for the poor of the city.

The Medressa closed after the Turks lost the Balkan wars (1912-1913) and Macedonia gained its independence, but the Imaret continued to feed the poor with soup and bread until 1923. From 1924 it was used to house Greek refugees from Asia minor.

The Imaret fell into disrepair for many years, but has recently been handsomely renovated and re-opened as a boutique hotel and restaurant. |

|

The chimneys and domes of the Imaret,

as seen from Kavala's main harbour. |

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Greek War of Independence

1821-1829 |

|

|

|

In 1821 the Greeks declared their war of independence with uprisings in the Morea (Peloponnese) and Crete. The sultan requested Mehmet Ali's help, and he sent his son and lieutenant Ibrahim Pasha (1789-1848, also born in Kavala) as head of his army to put down the revolt. For his efforts Ibrahim was granted governership of the two provinces.

The brutality of Ibrahim Pasha's methods, including the massacre, deportation and enslavement of civilians, has made him infamous in Greece. This savagery also invoked sympathy in European countries, resulting in the intervention of Britain, Russia and France. With their help, the Greeks destroyed Ibrahim Pasha's fleet at the decisive Battle of Navarino in 1827, which eventually led to a partial liberation of Greece in 1829. Macedonia only became part of modern Greece in 1913 after the Balkan Wars.

|

|

Theodoros Kolokotronis (1770-1843),

warrior hero of the Greek War of

Independence.

Bronze bust by Triantis, 1998.

At the west end of Koloktroni

Street, in the centre of Kavala,

near the Kamares aqueduct. |

|

| |

5 Drachmai coin of King Otto of Greece.

Minted in Paris in 1833.

Münzkabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden. |

| |

History

of Kavala |

Expansion of Kavala, 19th century |

|

|

|

Despite the disruption caused by the war between Greece and Turkey, Kavala began to develop and prosper as a port and trading centre during the 19th century. The city became an important location for the processing of tobacco, which was industrialized from the middle of the century. At first seasonal workers from the surrounding area and Thasos were employed for the period following the tobacco harvest in late summer, returning home when the work was finished. But as the trade grew many workers settled in the city.

As in other Ottoman cities such as Smyrna (Izmir), the tobacco trade in Kavala was mainly controlled by foreign merchants, and a new generation of European entrepreneurs, by skilfully negotiating advantageous trading concessions with the Turkish authorities, were able to introduce new production, processing, trading and shipping methods, and make larger profits quicker by supplying demands in domestic and foreign markets.

Tobacco was turned into a highly profitable cash crop as demand for the weed rapidly increased in Turkey and internationally, and smoking tobacco, particularly Balkan and Turkish blends, became fashionable among all classes. Kavala's "tobacco barons" became enormously wealthy, but the conditions of their workers remained miserable.

For centuries the city had been confined within the walls of the cramped citadel (the Panagia peninsula). However, after Sultan Abdulaziz I gave permission for building outside the walls in 1864, warehouses, factories and the grand representative houses of the wealthy, built in neoclassical and other eclectic styles, sprang up around the harbour. With such mansions and other buildings, the "tobacco barons" boldly demonstrated their wealth, power and influence. At the time this very foreign, literally outlandish architecture must have appeared quite alien to Turks and Greeks alike.

Kavala's tobacco boom ended after World War I and the end of the Ottoman Empire, when American tobacco (particularly Virginia tobacco) began dominating the international market, and the main centres of production and trade were in the United States and northern Europe. As a result tobacco processing and cigarette manufacture in Kavala gradually declined, and the area became merely a supplier of leaves as raw material for foreign factories and the greatly reduced domestic production.

See photos and information about the mansions

and other buildings from Kavala's tobacco boom on

Page 5: Activities and sightseeing in Kavala.

On the same page, information about

the Tobacco Museum of Kavala. |

|

The Wix Mansion, built around 1899

by Baron Adolf Wix von Zsolnay,

one of Kavala's "tobacco barons". |

|

| |

"View of Kavala", a watercolour by Edward Lear (1812-1888),

made from the northwest of the city on 26 September 1856. |

| |

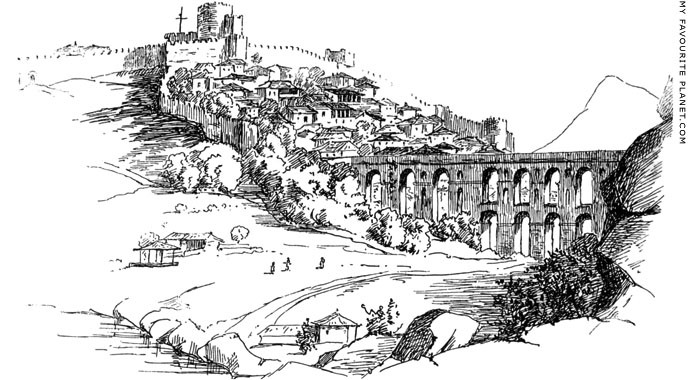

A drawing of Kavala in the late 19th century by Mary Adelaide Walker (1866-1950).

The undated drawing was made from the smaller harbour east of the walled citadel (the Panagia

peninsula), on the opposite side of the Kamares aqueduct from the main harbour. The hint of

buildings seen through the Kamares' arches indicates that the expansion of the city outside the

walls, first permitted by Sultan Abdulaziz I in 1864, was already well underway.

Source: Mary A. Walker, Old tracks and new landmarks, wayside sketches in Crete,

Macedonia, Mitylene, etc, page 134. Richard Bentley & Son, London, 1897. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

History

of Kavala |

Balkan Wars, 1912-1913 |

|

|

|

Although much of central and southern Greece and many of its islands had been freed from Turkish dominion between 1821 and the end of the century, Greek nationalists were still not satisfied. Their agenda was the "Megali Idea" (Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Great Idea), the dream to reunite Greek populations living throughout the old Byzantine territories. According to their new dream Greece would extend as far as Anatolia (western Turkey), with Constantinople (Istanbul) as the new Greek capital.

But they had rivals to their ambitions from nationalists of other emerging Balkan states whose ethnic populations (Albanians, Slavs, Bulgarians, Pomaks, Vlachs...), both Christian and Muslim, had become dispersed among Greeks over the centuries.

Pragmatists such as Eleftherios Venizelos (Ἐλευθέριος Βενιζέλος, 1864-1936), who became Greece's prime minister in 1910, had more immediate goals. He wanted to liberate Balkan territories such as Epirus, Macedonia and Thrace. To this end he promoted the Balkan League with Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria, which launched and won the Balkan wars of 1912-13. |

|

Eleftherios Venizelos, prime minister

of Greece 1910-1920 and 1928-1932.

Statue in Thessaloniki. |

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Macedonian Independence, 1913 |

|

|

|

The Ottoman forces were finally driven out of Macedonia, but as a result of agreements thrashed out between the Balkan League members under the influence of the great powers, it was carved up between Greece, Serbia (Slavs) and Bulgaria.

Today around 50% of Macedonia is part of Greece, around 40% forms the Republic of North Macedonia (formerly part of Yugoslavia), and 10% is in Bulgaria (the region of Blagoevgrad, also known as Pirin Macedonia). Various ethnic groups still straddle the borders, trying to maintain their customs, languages and dialects, and now and again attempting to stand up for their rights as minorities. "The Macedonian Issue" is still alive and kicking. Central governments of the region are still alternately ignoring, suppressing or table-thumping about it as their interests suit. |

|

|

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

World War I, 1914-18 |

|

|

|

There was not much time for Macedonians to enjoy their new freedom. The very upsurgance of Balkan nationalism that had freed them also sparked off World War I.

At first Greece remained neutral, but was persuaded to join the Allies by promises that they would assist the Greeks gain western Turkey. Bulgaria, which was not very happy about the small share of Macedonia it had been alloted, sided with Germany and Turkey. In 1916 the Bulgarians occupied Macedonia and Thrace but were forced to withdraw in 1917 as the Allies gained the upper hand. |

|

|

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Disaster in Asia Minor, 1922 |

|

|

|

After World War I the allies failed to keep their promises to Greece. However, the Greeks in Anatolia went ahead with their ill-fated rebellion against the Turks. The "Smyrna Affair" in 1922, in which Greek forces were routed, the city (today known as Izmir) destroyed by fire and the Greek population evacuated by Allied ships, finally put an end to the "Megali Idea".

Around 25,000 Greek refugees from Anatolia arrived in Kavala in the first of a series of forced population exchanges between Greece and Turkey.

The ensuing massive influx of newcomers from the Greek diaspora (from the Adriatic to the Black Sea, and eventually from the Levant and North Africa) naturally had a significant effect on the area's economy, culture and language. Likewise, the loss of the skills and talents of Turkish farmers, merchants and intellectuals made its own impact. |

|

|

|

| |

"Constantinoupolis 460 km" road sign near the Kamares Aqueduct,

on the road eastwards out of Kavala.

|

There are two such road signs in Kavala, both featuring the double-headed eagle, the symbol of the Byzantine Empire and the Greek Orthodox Church. They are part tourist attraction, part defiance or provocation.

Greeks still refer to Istanbul by its old name Constantinople, and the great dream of the "Megali Idea", espoused by politicians such as Eleftherios Venizelos during the early years of Greek independence, included regaining the old Byzantine capital from Turkey. This, as they say, is not going to happen any time soon, and the dream was ended in 1922. |

|

|

| |

The graffiti and stickers on the other sign at Kavala's main harbour show that

these days many young people have other things on their minds than Big Ideas. |

| |

History

of Kavala |

World War II, 1939-45 |

|

|

|

In 1941 Nazi Germany invaded Greece, and its fascist ally Bulgaria once again occupied Macedonia and Thrace until 1944. Once again the inhabitants of the region suffered brutal oppression. The Jewish community suffered an especially grim fate. The Jews were rounded up and sent to Nazi concentration camps. 60,000 people were deported from Thessaloniki.

The Macedonian Communist resistance, assisted by the Yugoslavian and Bulgarian resistance forces, played a vital role in the allied victory. |

|

|

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Civil War in Greece, 1946-1949 |

|

|

|

After World War II Macedonia became a Communist stronghold. The Greek left-wing leaders expected a share in government in recognition for their part in the defeat of the Nazis. However Britain and the USA (under Churchill and Truman respectively) would not tolerate a Communist-dominated Greece and backed the right-wing parties.

The civil war in Greece which consequently broke out between left and right was at least as bitter and bloody as the previous wars against foreign occupiers. Stories of barbarism and massacres on both sides are still controversial topics in Greece.

The left-wing forces, still backed by Communist Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, eventually proved no match for their enemies who received massive political, financial and military support from Britain and the USA.

Thousands of defeated left-wingers suffered imprisonment, internment, torture and execution. To avoid this fate many went into exile in eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, including 28,000 Macedonian children who were separated from their families. |

|

|

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Road to democracy, 1946-1981 |

|

|

|

During the Cold War (1945-89) Greece became a client state of the USA which maintained military bases and intelligence outposts.

As the country struggled to rebuild its economy, shattered by war, disunity and depopulation, Greek politics continued in its quagmire of left-right confrontations, characterized by intrigue and in-fighting on both sides, conspiracies, election fraud, strikes, demonstrations, assassinations and repression. Many more Greeks went to live abroad to escape the chaos and seek a better life.

The turning point came in 1967 when the Colonels' Junta, backed by the CIA, put an end to the turbulant attempts at democracy. The dictatorship was brutal and repressive, but ironically it was to have the effect of wiping the political slate clean. Political leaders on both sides, many of whom were now in exile, were forced to rethink their alignments and strategies.

When the Junta collapsed in 1974, PASOK (centre-left) and Nea Demokratia (centre-right) emerged as the two predominant political parties, with respective backing from the broad spectrum of left and right minority parties.

PASOK's election victory in 1981 and the reforms started by prime minister Andreas Papandreou proved that democracy had finally established a firm foundation. |

|

|

|

| |

History

of Kavala |

Today |

|

|

|

The re-establishment of democracy, the return of Greeks from abroad, membership of the European Union, the end of the Cold War and the increase in trade and tourism over the last two decades have all contributed to political stability and a degree of affluence in the country.

Kavala's position as a port serving a fertile agricultural area has helped it once more become a prosperous commercial centre. Its main exports are tobacco and grapes, but it also ships grain, timber and a wide variety of fruit and vegetables, as well as marble, which the locals claim is the whitest in the world.

Many of the city's fine buildings, including the neo-classical mansions and warehouses builty by wealthy tobacco merchants in the 19th century, the Imaret and the Halil Bey Mosque, have been renovated. The impression one gets today is of a modern, thriving, positive and friendly regional centre. It has not yet attracted the mass tourism which swamped other areas of Greece, and it is not a popular stop-over for island-hoppers and thrill-seekers, but there is enough to interest visitors here and in the surrounding area (see page 5: Activities and sightseeing in Kavala). |

|

Kavala Town Hall |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|