|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Middle East > Turkey > Pergamon > gallery 2 |

| Pergamon gallery 2 |

Pergamon art |

|

|

15 of 26 |

|

|

|

| |

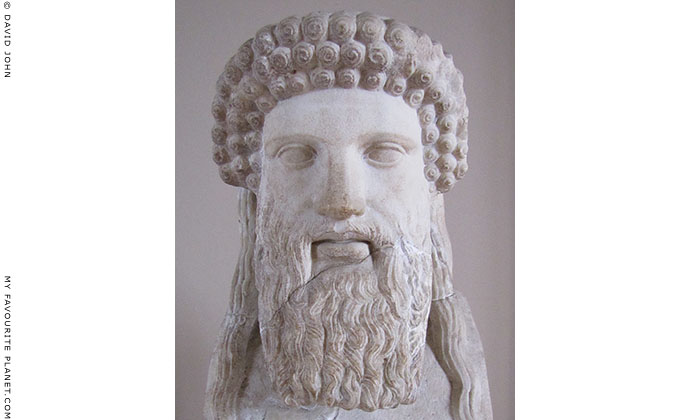

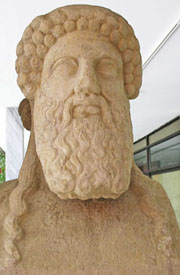

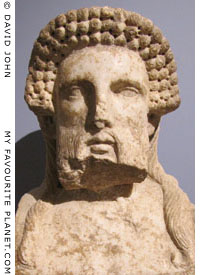

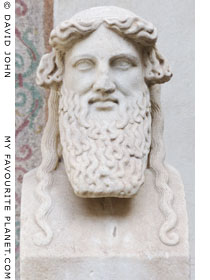

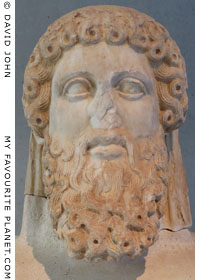

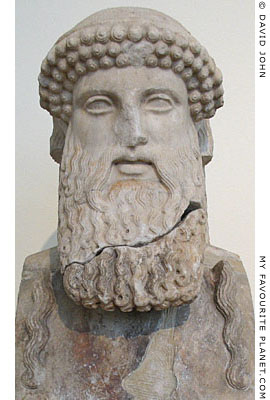

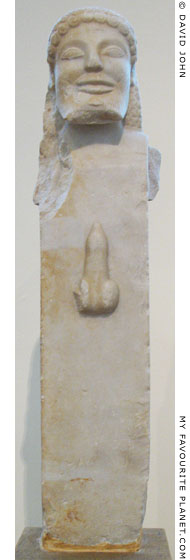

Herm of Hermes from Pergamon. "Copy of a herm attributed to Alkamenes". |

| |

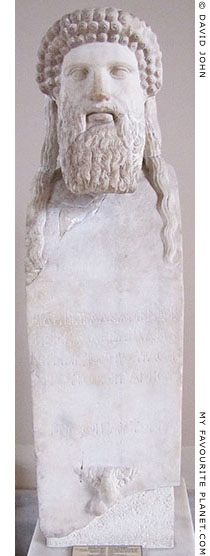

The 119 cm high marble herm [1], now in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, was discovered in Pergamon on 6th November 1903, in the ruins of "Shop 10", one of a row of shops on the main street, above the Upper Gymnasium, on the lower southwestern slope of the Acropolis. It is thought that at some point in history it had fallen into the shop from the so-called "House of Consul Attalos" [2] which stands just above it.

There is a replica of this herm in Bergama Archaeological Museum (Inv. No. 1433). There are also copies in Berlin and the Akademisches Kunstmuseum, Bonn [3].

The herm has been dated to around the 2nd or 3rd century AD, during the Roman Imperial period, and is believed to be a copy of an Archaic-style "Hermes Propylaios" (Hermes Before the Gate) made by Alkamenes in Athens in the 5th century BC (see below).

It is typical of a number of similar herms found around the Graeco-Roman world which belong to what has become known as the "Pergamon type" after this, the first to be found by archaeologists which bore an inscription associating it with Alkamenes, and one of the best preserved examples.

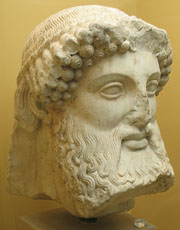

Compare this herm with another, less well-preserved head of the Pergamon type, in the Acropolis Museum, Athens, in the photo, below right.

During the Roman Imperial period, earlier Greek styles of statues were much admired and revered. Copies of Greek originals were made to order for official and private commissions. While some customers preferred the more "modern" Classical and Hellenistic style representations of gods and heroes, others favoured ancient, Archaic types which were also known in the Etruscan and early Roman world. Such statues, either copies of originals or made to imitate Archaic styles, are known as "archaistic".

A herm (or herma; Greek, Ερμές, ermes) was a tall, square-sectioned stone or bronze pillar, known as the shaft, often tapering to the base, on which was set the head or bust of a god, usually Hermes (read more about Hermes on the next page) or his half-brother Dionysus. Many sculpted portraits of famous mortals and heroes, such as Homer, Socrates, Demosthenes, Alexander the Great and Consul Attalos [see note 2], were also made in the form of herms, particularly during the Roman period. Herms often featured a dedicatory or descriptive inscription and a phallus and testicles, symbolic of fertility, on the front of the pillar.

According to Herodotus, the Athenians were the first Greeks to make images of Hermes in this way, having adopted a tradition of the Pelasgians, the name given to the indigenous people who lived in Greece before the arrival of the Hellenes.

"The Athenians, then, were the first Greeks to make ithyphallic images of Hermes, and they did this because the Pelasgians taught them. The Pelasgians told a certain sacred tale about this, which is set forth in the Samothracian mysteries."

Herodotus, Histories, Book 2, chapter 51, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Herms were set up as milestones and signposts along ancient roads, at street corners, as boundary markers, outside temples, public buildings such as baths and gymnasia, and private houses. This is another tradition said to have originated in Athens, perhaps in the mid 6th century BC. [4] The figures were believed to have supernatural apotropaic properties, that is, able to ward off evil and protect travellers (Hermes was the protector of travellers).

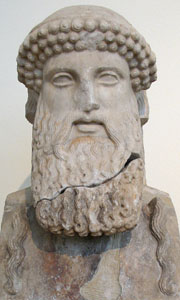

Although the head of this herm from Pergamon is often described as showing Hermes as an older, mature man, a closer look reveals a young, fresh, handsome face with clear eyes, a long straight nose (the front of which is a flat rectangle, following the angle of the forehead) and full lips framing a slightly open mouth.

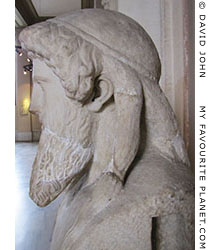

The suggestion of greater age is presumably due to the full beard which, again typical of the Pergamon type, is arranged in vertical rows (here in eight rows) of wavy curls. The rows end at the same level, giving the beard a square appearance. The moustache is long and the pointed ends hang over the beard. Most characteristic of this type of herm head are the three rows of snailshell curls framing the forehead and the two long wavy locks of hair (also referred to as tresses or ringlets) falling from behind the ears, with an end resting on the front of each shoulder.

This head has also been described as "severe", but while it does not have the technically idealized perfection of Classical statues (for example the cheekbones are quite flat), unlike true Archaic art it is actually quite a realistic portrait which reveals subtlety of modelling and secure knowledge of anatomy, based on careful study and observation. The purity of the crystalline white marble adds to the impression of clarity, beneficence and wisdom radiating from Hermes' face.

The height of such herms meant that the average ancient Greek would have viewed Hermes' face at around eye level, unlike the grand public statues of many other deities, often standing on plinths, which looked down on him or her. One can imagine that a believer passing such a herm along an ancient road would have felt great trust in and gained confidence from such a face of the Olympian protector of travellers and intermediary between the gods and mortals. |

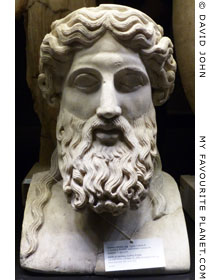

The herm in full length.

Herm of Hermes. Roman period

copy of a 5th century BC herm

attributed to Alkamenes.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Hermes in profile |

| |

| |

The Pergamon

herm of Hermes |

The herm, the Propylaia

and Alkamenes |

|

|

|

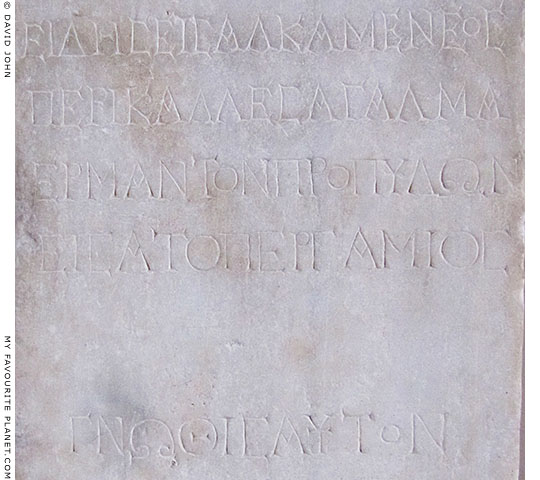

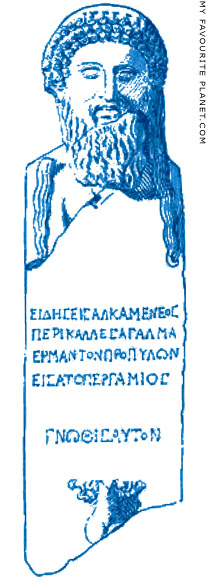

Greek inscription on the breast of the Herm.

Εἱδήσεις Ἀλκαμένεως

Περίκαλλες ἄγαλμα

Ἑρμᾶν τὸν Προπυλων

εἴσατο Περγάμιος.

Γνῶθι σέαυτον.

"You will recognize the extremely beautiful statue by Alkamenes,

the Hermes Before-the-Gate [Hermes Propylon].

Pergamios set it up. Know thyself." |

|

The Pergamon herm of Hermes bears the inscription:

"You will recognize the extremely beautiful statue by Alkamenes,

the Hermes Before the Gate (pro-pylon).

Pergamios set it up.

Know thyself."

(See a photo of the inscription above.)

At the time of the herm's discovery in 1903, the maxim "know thyself" was well-known from the inscription mentioned by Pausanias at the entrance to the Temple of Apollo at Delphi [5]. But what caused a minor sensation among archaeologists and historians was its claim that it was by Alkamenes and the reference to the Propylon. This was taken by many scholars to mean that it was a copy of a work by the 5th century BC sculptor Alkamenes (Αλκαμένης), possibly a pupil of Pheidias, who is known to have worked at the Athenian Acropolis during its rebuilding following its destruction by the Persians in 480-479 BC.

It also seemed reasonable at the time to conclude that the inscription's reference to "Ἑρμᾶν τὸν Προπυλων" (Hermes of the Propylon, Hermes before the gate) referred to the "Hermes of the Gateway" at the Propylaia of the Athens Acropolis mentioned by Pausanias in the 2nd century AD, and therefore that Alkamenes had made the lost original.

Pausanias wrote:

"Right at the very entrance to the Acropolis are a Hermes (called Hermes of the Gateway) and figures of Graces, which tradition says were sculptured by Socrates, the son of Sophroniscus, who the Pythia testified was the wisest of men, a title she refused to Anacharsis, although he desired it and came to Delphi to win it." [6]

(Let's ignore for the moment the possible ambiguity which may lead us to believe that Pausanias meant that the statue of Hermes and the figures of the Graces were attributed to Socrates, but perhaps note that much of what he wrote appears to modern scholars to be ambiguous or vague, which causes them severe headaches.)

According to this theory, Alkamenes, while working during the bloom of the Classical period of the mid 5th century BC, appears to have chosen, or was commissioned, to represent his "Hermes of the Gateway" for the new Propylaia (built around 437-432 BC), the monumental gateway to the Athens Acropolis, in archaistic style, with a long beard and "snailshell" or "corkscrew" curls.

Many scholars seemed convinced that the Pergamon herm was a replica of a work by Alkamenes' and neatly connected it to the Hermes of the Athens Propylaia mentioned by Pausanias. In 1926 Sir Charles Waldstein wrote:

"The work which we have placed first among extant monuments to be identified, beyond all doubt, with Alcamenes is the Hermes Propylaios from Pergamon. The high value of this lies in the fact that it has a definite inscription identifying it with Alcamenes." [7]

However, the widely accepted identification of this type of herm, known as the "Pergamon type", with Alkamenes and the Athens Propylaia has been challenged. Further doubts arose after another herm of the Roman Imperial period was unearthed at Ephesus in 1928, bearing an inscription in iambics which boasted:

οὔκ εἰμι τέχνα

τοῦ τυχόντος,

ἀλλά μου

μορφὰν ἔτευξε[ν,]

ἣν σκοπῆς, Ἀ̣[λκα]-

μένης.

"I'm not just anyone's work; my form,

If you will look closely, was wrought by Alkamenes." [8]

The "Ephesos type" Hermes is quite different, distinctly more archaic and less lifelike than the Pergamon type, leading to the suspicion that either one or the other, or both have no connection with the purported work by Alkamenes. It has been speculated that he may have made two different types of herm, but this appears to be wishful thinking.

Pausanias was the only ancient author to mention a statue of Hermes at the Athens Propylaia, but he does not describe it or say anything more about it; he does not specify that the image of Hermes was in the form of a herm and he certainly does not say that it was by Alkamenes. The original has not been discovered, so we have no way of knowing for certain what it looked like. Apart from these herm inscriptions, there is no other evidence, literary or epigraphical, to connect a Hermes by Alkamenes with the Athens Propylaia.

The German archaeologist Alexander Conze suggested that "Propylaios" was not a reference to a particular gateway, but an epithet for Hermes - Hermes Before the Gate - as in Hermes Hegemonios (ἡγεμόνιος, Leader), Perpheraios (Wanderer), Diactoros (Messenger), Kriophoros (Κριοφόρος, Ram-Bearer). Some of these epithets were also local cult names for the god. [9]

Another consideration is that the Classical gateway to the Athens Acropolis, designed by Mnesikles [10], was known as the Propylaia (Greek, Προπύλαια: pro, before or in front of, plus the plural of pylon or pylaion, gate; literally "that which is before the gates"), the plural of propylon. The Propylon (Προπυλων, singular) was the name of the more ancient gateway on the same site, which was destroyed during the Persian invasion of Xerxes in 480-479 BC. Both Pausanias and the inscription on the Pergamon herm clearly refer to the "Propylon" not "Propylaia" (see photo above).

Therefore, if there is any direct connection between either the Pergamon or Ephesus herm and the gatweway of the Athens Acropolis, it may be with the older gateway. This would suggest that such a herm stood before this gateway in the Archaic period, and begs several questions, for example:

1. Was the prototype for the Pergamon herm actually Archaic, rather than one imitating the ancient style?

2. Is it possible that an Archaic Hermes Propylon survived the Persian destruction - even to the time of Pausanias (2nd century BC)? It is thought that some sacred images were hidden before the Persians arrived.

3. If so, was it created by an earlier Alkamenes than the one associated with Pheidias? In ancient Greece a man's name was often passed on to his son or grandson.

4. If the original was by the Alkamenes of the mid 5th century BC, did he base his Hermes Propylon on one which in living memory had stood on the same site? |

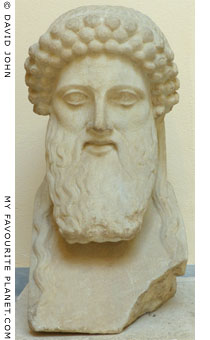

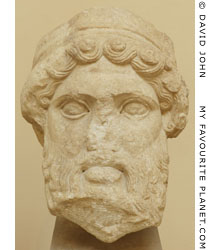

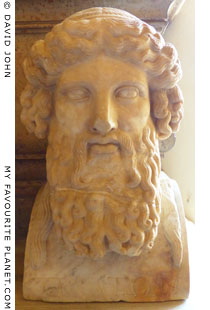

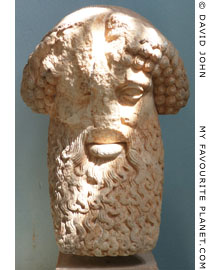

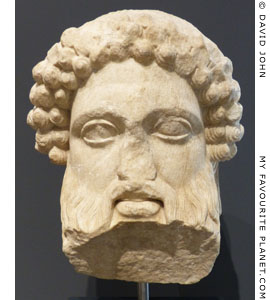

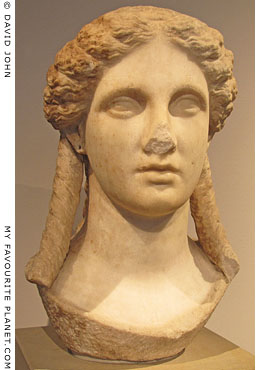

Head of "Hermes Propylaios",

from a "Pergamon type" herm.

Found at the Athens Acropolis.

Pentelic marble. 1st century BC. Thought to be a copy of the

herm by Alkamenes,

set up around 430 BC at

the Propylaia of

the Athens Acropolis.

Acropolis Museum,

Athens. [11] |

| |

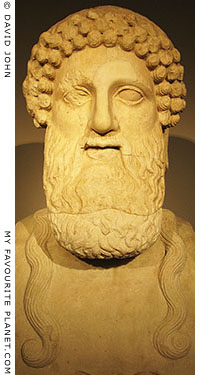

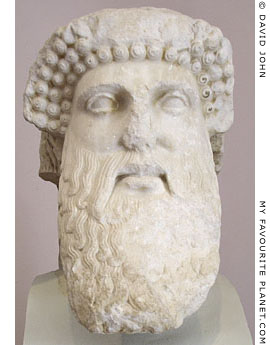

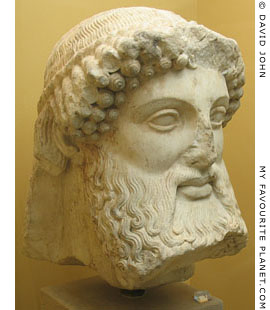

Head of Hermes. Detail of a

double herm with Hermes and

Apollo, from the Panathenaic

Stadium, Athens. Pentelic

marble. 2nd century AD.

National Archaeological

Museum, Athens. [12] |

| |

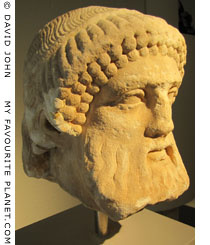

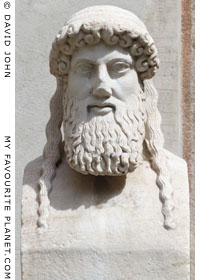

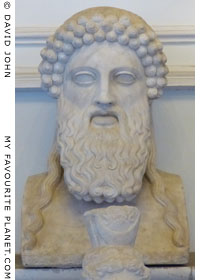

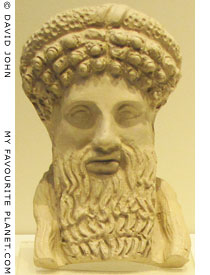

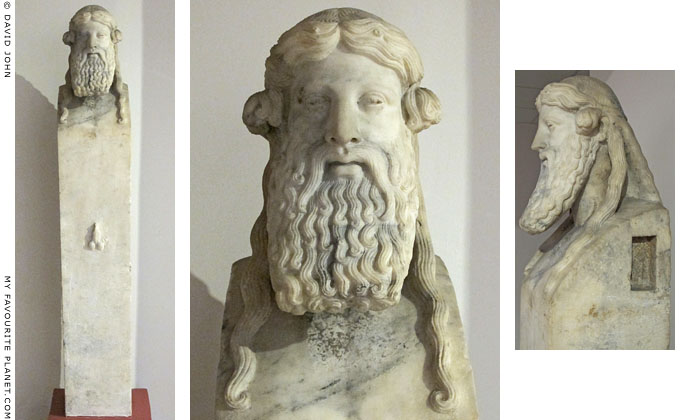

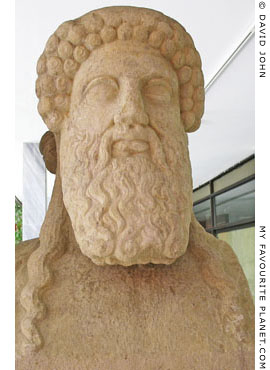

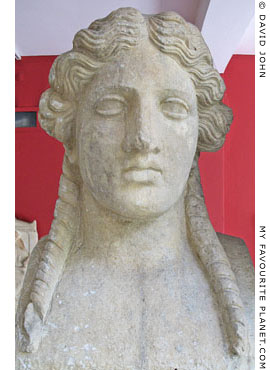

Herm of the "Pergamon type".

Pentelic marble. 1st century

BC - 1st century AD.

Provenance unknown. [13]

National Archaeological

Museum, Athens. |

| |

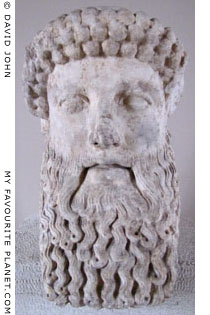

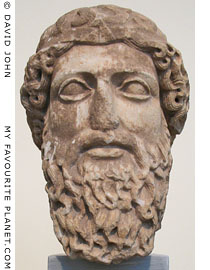

Head of a Hermes herm from

the Ancient Agora, Athens.

Pentelic marble.

2nd century AD. [14]

Ancient Agora Museum,

Athens. |

| |

|

Head of a herm of Hermes

from the agora of Thasos,

Greece. 4th century BC.

Height 24.2 cm.

Thasos Archaeological

Museum. Inv. No. 11. |

|

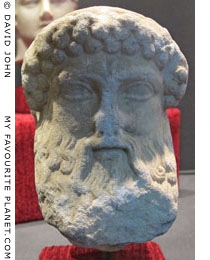

Head a herm of Hermes

from Amphipolis, Macedonia,

Greece. Archaistic work,

2nd-1st century BC.

Amphipolis Archaeological Museum. |

|

A much smaller head,

similar to the Pergamon herm,

thought to represent Hermes.

Marble, Roman period. [15]

Izmir Archaeological Museum. |

|

One of a pair of similar busts of

Hermes found in Ostia Antica,

Rome. This one was discovered

in the Aula dei Mensores.

Archaeological Museum of

Ostia, Rome. Inv. No. 7.

(Not labelled in museum.) |

|

One of a pair of herms flanking

a fountain in the courtyard

of the Palazzo Altemps, Rome

(see photo and details below).

The herm on the right of the

fountain in the Palazzo Altemps. |

|

Herm of Hermes.

Medium-grained crystalline marble. Roman period, 2nd century AD.

This herm, inside the entrance to the museum, is described by the official guidebook as "on the model of the Hermes created in the 5th century BC by the artist Alcamenes for the Propylaea in Athens".

From the Mattei Collection.

Palazzo Altemps, National

Museum of Rome, Italy.

Inv. No. 80731. |

Another very different head in

Ostia Museum, described in the

official guidebook as "a copy of

Hermes Propylaios by Alcamene".

Pentelic marble, 2nd century AD.

Found in 1910 in the Decumanus

near the Theatre of Ostia.

Archaeological Museum of Ostia,

Rome. Inv. No. 88. |

|

|

A pair of herms set up to flank a late 16th century fountain, designed to look like an ancient

sacred grotto, in the courtyard of the Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome, Italy.

Two of seven herms of Pentelic marble depicting various deities (Hermes, Herakles, Dionysus and

Athena, as well as Theseus and a discobolus), found in 1621 on the property of Cardinal Ludovisi

in Rome, and set up in the gardens of the Villa Ludovisi. Six are now exhibited around the courtyard,

and the seventh is in the Capitoline Museums. All are thought to be the work of a single artist in

the 2nd century BC, based on earlier Greek models.

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome. Inv. Nos. 8611, 8617, 8621, 8627, 8639, 8643. |

| |

Herm of Hermes (displayed

behind a bust of Isis) from

Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli.

117-138 AD.

Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline

Museums, Rome.

Donated to the museum in

1748 by Pope Benedict XIV.

Inv. No. MC397. |

|

Head of Hermes.

Part of a herm from the island

of Tenedos (Bozcaada, Turkey).

Roman period. Archaistic.

Height of head 42.5 cm.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 740 T. Cat. Mendel 529. |

|

"Herm of a bearded divinity"

in the Hall of Philosophers of

Rome's Capitoline Museums.

Labelled as a Roman copy of

a 5th century BC Greek original.

This is one of three similar herms

in the Palazzo Nuovo bearing the

modern inscription "Platon".

As with many of the busts in this

room of the museum, the identity

of individuals is uncertain.

Sale dei Filosofi, Palazzo Nuovo,

Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Albani Collection.

Inv. No. MC405. |

|

Herm of Dionysus, Hermes'

brother. Roman period,

1st - 2nd century AD.

Probably a copy of a 5th

century BC Greek original

in late Archaic style.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. K. 207.

Read more about this herm

on the Dionysus page of

the MFP People section. |

|

Modern cast of a head of

Hermes, made from part

of a 1st century BC pottery

mould for a small herm

found in the Pella Agora.

Height 11.5 cm.

Pella Archaeological Museum,

Macedonia, Greece.

Mould No. 81/224.

See an example of a

terracotta herm from Pella

below. |

|

Head of a bearded god found

in 1886 in a sanctuary of

Eetioneia in Piraeus, Greece.

Thought to be either Hermes

or Zeus. Perhaps the head of

a herm dedicated by Python

from Abdera, Thrace, a work

of the Parian sculptor Euphron.

450-440 BC. Pentelic marble.

National Archaeological

Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 332. |

|

Head of a herm of Hermes

from the Athens Acropolis.

Pentelic marble. 2nd century AD.

Acropolis Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. Acr. 14877. |

|

Herm of Hermes, Curtius B type.

First half of the 1st century AD,

"after an original dating from

the later 5th century BCE".

Height 47 cm, width 31 cm,

depth 27 cm.

Skulpturensammlung,

Albertinum, Dresden.

Inv. No. Hm 069. |

|

Head of a herm of Hermes

from Eleusis.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum,

Attica, Greece. Inv. No. 5118. |

|

| |

A marble herm of the Roman period from Ephesus, with no inscription.

Provenance not stated on museum labelling.

1st century AD (?). Height 1.65 metres, width 29 cm, depth 25 cm.

Department of Sculpture, Izmir Museum of History and Art,

Kültürpark, Basmane. Inv. No. 003.224. [16] |

| |

The Pergamon

herm of Hermes |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. The Pergamon Hermes Propylon

"Herme of Hermes Propylaios" or "Hermes of Alkamenes".

Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Inventory Number 1433 T, Cat. Mendel 527.

Dimensions

Total height of herm: 119.5 cm

Width of herm shaft: 32 cm

Depth of herm shaft: 29 cm

Height of head, from top of hair to tip of beard: 40 cm

When discovered the marble of the herm was described as being flecked with small crystals and having a warm, golden yellow tone (Altmann, 1903). The surface of the inscription was polished, but the back of the herm had only been roughly worked. Traces of red-brown colour were still visible on the right side of the back of the head and on the right side of the shaft.

The modern restoration included replacement with plaster of missing pieces of the hair locks at the shoulders, parts of the shoulders and the beard.

See:

Franz Winter, Altertümer von Pergamon, Band VII, Text I: Die Skulpturen, mit Aussnahme der Altarreliefs. pages 48-53. (The antiquities of Pergamon, Volume 7, Text 1: The sculptures, with the exception of the Altar reliefs). Königliche Museen zu Berlin. Verlag von Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1908.

Athenische Mitteilungen, XXIX, 1904, page 179; Athenische Mitteilungen, XXXII, 1907, page 185.

Gustave Mendel (1873-1938), Catalogue des sculptures grecques, romaines et byzantines, Tome Second, pages 234-237. Musée Impérial, Constantinople (Istanbul), 1914.

2. The House of Consul Attalos

This large house, discovered in 1903, is thought to have been originally built around 200-100 BC, in the time of the Attalid kings, and became the home of a certain Consul Attalos during the Roman period, perhaps as late as the second or third century AD. Despite his high rank, nothing is known of Attalos (Greek, Ἄτταλος; Latin, Attalus), and his name (which had become popular in the Roman Empire) is not included in lists of consuls of Rome. He may have been a "consul suffectus", a high-ranking official appointed to replace an elected consul who had died or resigned. It has been suggested that he may have been either Menyllius Attalus, proconsul Asiae, or Claudius Attalus Paterculianus, legatus Bithyniae, who are mentioned in inscriptions elsewhere.

The only clue as to the identity of this Attalos is the inscription on one of the two herm shafts found at the house, which apparently held bronze portrait heads of the wealthy resident. The short inscription states that the Roman Consul Attalos held a municipal religious office.

Ἄτταλος οΰτος

ὁ τήνδε θεῶν

πανυπείροχον

εἵσας,

Ρωμαίων ῠπατος,

πρόπρολός ἐστί θεᾶς.

The significance and responsibilities of this office, and which deity's cult (πανυπείροχος θεῶν, panypeirochos theon) he served, remain uncertain; Hera, Kybele and Isis have been suggested by scholars.

It seems that Attalos renovated the peristyle house in grand style, as it is decorated with the large wall paintings which can still be seen at the site. The floor mosaics of the house are thought to be Hellenistic. The inscription on the second of the two herms discovered here (1905), a Homeric epigram inviting his friends to come and drink wine with him, indicates that he was an educated man of taste, and that he hosted grand dinner parties. |

|

Drawing of the Pergamon

"Hermès d'Alcamène" from

Gustave Mendel's catalogue

of the Istanbul Archaeological

Museum, 1914. |

|

3. Copies of the Pergamon Hermes Propylon

The cast in Berlin, Germany, known as "Herme des Alkamenes, sogenannte Hermes Propylaios, aus Pergamon" ("Herm of Alkamenes, so-called Hermes Propylaios, from Pergamon"), is kept in the Abguss-Sammlung Antiker Plastik (cast collection of ancient sculpture) of the Freie Universität.

V 207, Inv. No. 83/33.

As can be seen in the photo, right, the cast was made before the restoration of the original herm, particularly the repairs and additions to the side-locks and beard. The copy is a fine piece of casting work, but completely lacks the lifelike quality lent by the ancient marble, and the inscription is barely visible.

It is not normally exhibited, but was displayed in the Pergamon Museum in 2012, during the special exhibition "Pergamon. Panorama der antiken Metropole" (Pergamon. Panorama of the Ancient Metropolis), which featured objects and documents relating to early archaeological excavations at Pergamon.

See the exhibition catalogue in German:

R. Grüßinger, V. Kästner, A. Scholl, Pergamon. Panorama der antiken Metropole, Objektkatalog, 3 Leben in der Stadt, page 457-458, Catalogue no. 3.19. Antikensammlung der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin and Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg, 2012.

And:

Herme des Alkamenes, sog. Hermes Propylaios, aus Pergamon, University of Cologne, Arachne website, in German.

The copy in Bonn, Germany, "Herme des Hermes Propylaios", Inv. No. 1300, is in the Akademisches Kunstmuseum - Antikensammlung der Universität (The Academic Art Museum - Antique Collection of the University of Bonn).

See: Herme des Hermes Propylaios, University of Cologne, Arachne website (in German).

4. The setting up of public herms

The dialogue Hipparchos, attributed to Plato (Πλάτων, 428-347 BC), is named after Hipparchos (Ἵππαρχος, assassinated by Harmodius and Aristogeiton in 514 BC), one of the two sons of the Athenian tyrant Peisistratos (Πεισίστρατος, ruled circa 546-527 BC). In this dialogue, the philosopher Socrates (Σωκράτης, circa 470-399 BC) praises Hipparchos as a wise man, a benefactor to the people of Athens and Attica and a champion of the arts and education. Among the wise deeds of Hipparchos mentioned by Socrates is the setting up herms in along the streets and roads of Attica, although he does not explain the educational function of these figures:

"... All this he (Hipparchos) did from a wish to educate the citizens, in order that he might have subjects of the highest excellence; for he thought it not right to grudge wisdom to any, so noble and good was he. And when his people in the city had been educated and were admiring him for his wisdom, he proceeded next, with the design of educating those of the countryside, to set up figures of Hermes for them along the roads in the midst of the city and every district town."

Plato, Hipparchus, section 228c-228d. At Perseus Digital Library.

5. Pausanias on the maxim "Know thyself" at Delphi

Pausanias (Παυσανίας), 2nd century AD Greek travel writer, thought to be from Lydia in Asia Minor. His only known book is Description of Greece (Ἑλλάδος περιήγησις) Here he discusses the "Seven Wise Men" or "Seven Sages" of the ancient Greek world and their relation to Delphi:

"In the fore-temple at Delphi are written maxims useful for the life of men, inscribed by those whom the Greeks say were sages. These were: from Ionia, Thales of Miletus and Bias of Priene; of the Aeolians in Lesbos, Pittacus of Mitylene; of the Dorians in Asia, Cleobulus of Lindus; Solon of Athens and Chilon of Sparta; the seventh sage, according to the list of Plato, the son of Ariston, is not Periander, the son of Cypselus, but Myson of Chenae, a village on Mount Oeta. These sages, then, came to Delphi and dedicated to Apollo the celebrated maxims 'Know thyself' and 'Nothing in excess'."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 24, section 1.

At Perseus Digital Library.

"Know thyself" (γνῶθι σεαυτόν, gnothi seauton) is attributed to the philosopher and mathematician Thales of Miletus (circa 624-546 BC), and "Nothing in excess" (μηδὲν ἄγαν, meiden agan) to the Athenian legislator and reformer Solon (circa 638-558 BC).

6. Pausanias on the Hermes of the Gateway of the Athens Acropolis

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 22, section 8. At Perseus Digital Library.

In Greek:

"κατὰ δὲ τὴν ἔσοδον αὐτὴν ἤδη τὴν ἐς ἀκρόπολιν Ἑρμῆν ὃν Προπύλαιον ὀνομάζουσι καὶ Χάριτας Σωκράτην ποιῆσαι τὸν Σωφρονίσκου λέγουσιν, ᾧ σοφῷ γενέσθαι μάλιστα ἀνθρώπων ἐστὶν ἡ Πυθία μάρτυς, ὃ μηδὲ Ἀνάχαρσιν ἐθέλοντα ὅμως καὶ δι᾽ αὐτὸ ἐς Δελφοὺς ἀφικόμενον προσεῖπεν."

Pausaniae Graeciae Descriptio, Book 1, chapter 22, section 8.

3 volumes, in Ancient Greek. Teubner, Leipzig, 1903. At Perseus Digital Library.

7. Sir Charles Waldstein on the "Hermes Propylaios" from Pergamon

Sir Charles Waldstein, Alcamenes and the establishment of the Classical type in Greek art, Chapter 11 The Hermes Propylaios, page 153. Cambridge University Press, 1926. Preview at googlebooks. |

|

The Berlin plaster cast of the Pergamon Hermes Propylon. |

|

|

8. Ephesos Type Hermes

The "Alkamenes herm of the Ephesus type".

Izmir Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 675.

Marble. Height 220 cm.

The first published description of the Ephesus herm was by Camillo Praschniker, Der Herme des Alkamenes in Ephesos, in Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien (ÖJh), Volume 29 (1934), pages 23-31.

Inscription: Ephesos 2100.

See: epigraphy.packhum.org/text/249827

at The Packard Humanities Institute.

It was one of a pair of over-lifesize herms, of Hermes and Herakles, discovered flanking the doorway to Apodyterium (Room VI) of the Vedius Gymnasium. Both herms were badly damaged: most of the face, beard and throat of the "Alkemenes" herm were missing and the shaft was broken in pieces; of the other herm only the shaft was found.

23 Hermes herms have been identified as Ephesus types, including those in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome (Inv. No. 121008), in the Hermitage, Saint Petersburg (from the Villa Hadriana, Inv. No. A 26) and in the Glyptothek, Munich (Simonetti Collection. Inv. No. DV 37).

See:

D. Willers, Zum Hermes Propylaios des Alkamenes. Jahrbuch Deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts (JdI) Band 82, 1967, pages 37-109.

Anastasia Fiolitaki, Archaistic elements in Greek art and architecture of the fourth century BC, with particular reference to works from Ionia and Caria. PhD thesis, University of London, 2001.

The remains of another herm pair were also found in the Gymnasium, and a number of other herms have been unearthed around the ancient city.

Another, very different head of Hermes, 135 cm high, from a herm of the 2nd century AD, was found near the Gate of Mazeus and Mithridates in Ephesus, and is now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Antikensammlung, Vienna, Austria. Inv. No. I 848.

For further discussion on Pausanias' "Hermes of the Gateway" and its purported connection to Alkamenes and the herms from Pergamon and Ephesus, see:

Jane E. Francis, Re-writing Attributions: Alkamenes and the Hermes Propylaos, in Stephanos: Studies in honor of Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, edited by Kim J. Hartswick and Mary Carol Sturgeon, Chapter VI, pages 61-68. UPenn Museum of Archaeology, 1998. Preview at googlebooks.

Archaeological museums in Izmir

Many books and academic journals still state that the Ephesus herm is in "Izmir Basmahane Museum". However, this museum, now known as the Eski Arkeoloji Müzesi (Old Archaeological Museum), was closed in 1951.

The Basmahane Archaeological Museum (Arkeoloji Müzesi), officially named Asar-i Antika Müzesi, was housed in the former Greek Orthodox Ayavukla (Gözlü) Church, dedicated to saints Agios Boukolos and Polycarp (patron saints of Smyrna), in the Basmahane district, from 1924, and opened to the public in 1927.

In 1951 the exhibits were moved to the National Educational Pavilion, built for the İzmir International Fair in the nearby Kültürpark (Culture Park). The new museum, Izmir Museum of History and Art (Izmir Tarih ve Sanat Müzesi), organized in three departments (precious artifacts, ceramics and sculpture) in separate, adjacent buildings, is still home to one of the largest collections of antiquities from the Turkish Aegean region.

The 19th century Ayavukla Church is in the former Armenian district of Basmahane. The name of the district, since contracted to Basmane, was taken from a weaving factory which once stood on or near the location of the present Basmane railway station. The church, now known as Aziz Vukolos Kilisesi, was the only church in central Izmir to survive the devastating 1922 fire. After the museum was moved to the Kültürpark, the church was used for some years to store unsorted antiquities, but was later abandoned and became derelict. It was restored 2009-2012, and is now used as a cultural centre. It is open daily, admission free.

The newer Izmir Archaeological Museum (İzmir Arkeoloji Müzesi) was opened in 1984, in Bahribaba Park, about 500 metres southeast (and uphill!) from Konak Square.

The Ephesus "Alkamenes herm" is currently in the Archaeological Museum, although during my last visit (August 2012) it was not on display. Regina Hanslmayr published a photo the herm's shaft (Inv. 675; ÖAL Inv. EPH 15123) in 2003. According to the caption, "the head had been removed at the time". See the photo and article (in German) at:

Regina Hanslmayr, Zum Bedeutungswandel des griechischen Hermenmals in römischer Zeit am Beispiel Ephesos. Zeitschrift für klassische Archäologie 29 / XII / 2003, 10. Österreichischer Archäologentag.

See also an illustrated article about the foundation of Smyrna (Izmir) by Alexander the Great in the MFP People Section.

9. Alexander Conze on Hermes Propylaios

The herm was first published by Alexander Conze in Hermes Propylaios, Sitzungsberichte der Berliner Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1904, pages 69-71.

See also: Franz Winter, Altertümer von Pergamon, Band VII, Text I: Die Skulpturen, mit Aussnahme der Altarreliefs. pages 48-53. (The antiquities of Pergamon, Volume 7, Text 1: The sculptures, with the exception of the Altar reliefs.) Königliche Museen zu Berlin. Verlag von Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1908.

10. Plutarch on Mnesikles as architect of the Athens Propylaia

Plutarch (Greek: Πλούταρχος, name as Roman citizen Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, Μέστριος Πλούταρχος, circa 46-120 AD), Greek historian, biographer and essayist, born in Chaeronea, Boeotia.

"The Propylaia of the Acropolis were brought to completion in the space of five years, Mnesicles being their architect."

Plutarch's Lives, Pericles, 13.7-8. English Translation by Bernadotte Perrin. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann Ltd., London. 1916. At Perseus Digital Library.

See the article about the Propylaia of the Athens Acropolis: Athens Acropolis gallery, page 10). |

Head of the Ephesus "Alkamenes herm".

Izmir Archaeological Museum.

photo: Camillo Praschniker |

| |

Head of a herm of "Hermes Propylaios"

of the Ephesus type.

Pentelic marble. Early Roman Imperial

period. Found in 1935 near the Villa

dei Quintili, Via Appia Nuova, Rome.

National Museum of Rome,

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme.

Inv. No. 121008. |

| |

Ayavukla Church, Basmane, Izmir. |

| |

Inside the newly-restored Ayavukla Church. |

| |

Road sign to the Ayavukla Church, or

Aziz Vukolos Kilisesi, Basmane, Izmir. |

| |

Entrance to Izmir Museum of History

and Art (Izmir Tarih ve Sanat Müzesi),

Kültürpark, near Basmane station. |

| |

Izmir Archaeological Museum, Bahribaba

Park, southeast of Konak Square. |

| |

|

11. "Hermes Propylaios", Acropolis Museum, Athens

Acropolis Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. Acr. 2281.

Found on the Athens Acropolis.

Pentelic marble. 1st century BC.

A herm head of the "Pergamon type", and like Pergamon herm it has three rows of snailshell curls framing the forehead and symmetrical groups of curls on the beard. The shoulder-length locks of hair are now missing.

I have not yet found any recent literature which examines this sculpture in any depth; it is usually mentioned briefly in relation to the Pergamon herm.

See:

Ismini Trianti, The Acropolis Museum, pages 395 and 402.

Eurobank / Latsis Group. Published by OLKOS, Athens, 1998.

E-book in English and Greek. |

|

Head of a "Pergamon type" "Hermes

Propylaios", from the Athens Acropolis.

Pentelic marble. 1st century BC.

Acropolis Museum, Athens. |

| |

12. Double herm with Hermes and "Apollo"

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. NAMA 1693.

In the inner garden of the museum.

Found in the Panathenaic Stadium, Athens.

Pentelic marble. 2nd century AD.

Height 144 cm.

Another "Pergamon type" representation of Hermes, on a taller herm shaft, back-to-back with a head of Apollo (or perhaps Dionysus, see photo, below right).

In this photo the marble on Hermes' side of the herm appears much redder than it should, as it faces a bright red painted wall.

The general appearance of this Hermes, with slightly softer, rounder features, the closed mouth and the way the stone has been weathered, make it appear similar to the Herm in the Acropolis Museum (see photo above). Both heads are set so they appear to be looking up, rather than straight ahead.

According to the museum labelling, the head of Apollo, which also has shoulder-length tresses, is a copy of a type based on a 5th century BC original. In the early days of modern archaeology, difficulties arose in distinguishing this kind of Classical image of a young, clean-shaven, feminine-looking Apollo from similar images of Dionysus. Many such sculptures were at first thought to be of goddesses, as in the case of a 4th century BC head of Apollo or Artemis, now in the Altes Museum, Berlin (see photo below), which is similar to the Apollo of this herm.

This is one of the four herms which stood along the centre of the race course of the Panthenaic Stadium, which was 600 Greek feet long. All four herms were found by archaeologists during excavations prior to the restoration of the stadium for the first modern Olympic Games in 1896, and two are still on display on the stadium track (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 32). |

|

Head of Hermes. Detail of a double

herm of Hermes and Apollo from the

Panathenaic Stadium, Athens.

Pentelic marble. 2nd century AD.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 1693. |

|

| |

Apollo or Artemis? This head, acquired

in Athens in 1844, was for many years

described merely as "a female head".

Parian marble. Height 56 cm.

Hellenistic, 330-300 BC.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 616. |

|

Head of Apollo on the double herm

of Hermes and Apollo above.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 1693. |

|

| |

13. Herm of the "Pergamon type"

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. NAMA 107.

Pentelic marble. Provenance unknown.

1st century BC - 1st century AD.

The similarities between the head of this herm and that of the Pergamon herm are immediately apparent. Unfortunately, only three fragments of the upper part of the shaft has survived, so if there was an inscription it has been lost. Parts of the side locks are missing, and some of the curls, the nose and beard have been damaged. Orange, red and black colouring can be seen on beard and breast. Despite the famed whiteness of Pentelic marble, this sculpture now looks decidedly grey. |

|

Herm of the "Pergamon type".

Pentelic marble.

1st century BC - 1st century AD.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 107. |

|

| |

14. Herm head in the Agora Museum, Athens

Museum of the Ancient Agora, Athens.

Inv. No. S 2499.

Pentelic Marble. 2nd century AD.

Height 35 cm.

Found in 1972 in the Royal Stoa, just north of the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios, at the northwest corner of the Ancient Agora of Athens. It had been deliberately buried in a pit (Deposit G 4:3) with a hoard of coins of the second half of the 4th century AD. It is thought that it was originally set up on the north side of the Agora, along the route of the Panathenaic procession, in an area where so many herms were set up that it was known as "the Herms".

"Menekles or Kallikrates in his work on Athens writes, 'From the Stoa Poikile and the Stoa Basileios extend the so-called Herms. Because they are set up in large numbers both by private individuals and by magistrates they have acquired this name.'"

Harpokration

Hermes, as the god of trade and commerce (and thieves) was obviously very popular in the Athens Agora; and as the god of doorways, his herms were set up in front of every house in the city. According to Pausanias, "the Athenians are far more devoted to religion than other men... they were the first to set up limbless Hermae".

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 24, section 3. At Perseus Digital Library.

See Also:

agathe.gr/id/agora/object/s%202499

T. Leslie Shear Jr., The Athenian Agora, excavations of 1972, Hesperia, XLII, 4, pages 406-407 and plate 76 b.

John McK. Camp II, The Athenian Agora: a short guide to the excavations, page 40. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2003.

John McK. Camp II, Gods and heroes in the Athenian Agora, page 12. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1980.

agathe.gr is the excellent website dedicated to the archaeological excavations in the Athenian Agora, conducted by the American School of Classical Studies.

15. Small head of Hermes in Izmir

Probably from a small herm or statuette. As with many of the exhibits in the otherwise excellent Izmir Archaeological Museum, the label for this head, in Turkish and English, does not mention the place in which it was found, or state the inventory number. Some objects have no label at all, and at the time of my last visit (August 2012), there was no guide book or catalogue available for visitors.

16. Herm in Izmir Museum of History and Art

Since writing the caption for the above photo, I have discovered a little more about this herm.

A herm of the Roman or Hellenistic period from Ephesus

(one source states 1st century AD).

Medium crystalline gray-white marble.

Height 1.65 metres, width 29 cm, depth 25 cm.

Department of Sculpture, Izmir Museum of History and Art (Izmir Tarih ve Sanat Müzesi), Kültürpark, Basmane.

Inv. No. 003.224 (in some publications 3224).

See: Serdar Aybek, Mehmet Tuna, Mahir Atici. İzmir Tarih ve Sanat Müzesi Heykel Kataloğu (Izmir History and Art Museum Sculpture Catalogue), item 42, page 61 (in Turkish). Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Cultural Heritage and Museums General Directorate), Ankara 2009.

The catalogue entry has a detailed description of the herm's appearance, but not information about its history or when or where it was found. |

| |

Head of "Hermes of Alkamenes".

2nd century AD.

Ancient Agora Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. S 2499. |

| |

Small terracotta herm from a

household shrine in Pella, Greece.

Late 4th - early 1st century BC.

Pella Archaeological Museum,

Macedonia, Greece. |

| |

Archaic marble herm from Siphnos,

Greece. Island marble. About 520 BC.

Height 66 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 3728. |

| |

| |

Marble sarcophagus described as "anthropoid sarcophagus of a woman in Greek style".

From the Royal Necropolis of Sidon, Chamber No. 7. 470-460 BC.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 498 T. Cat. Mendel 80.

|

The Royal Necropolis of Sidon is famous for its lavish and unusual sarcophagi, which include the "Alexander Sarcophagus" (Iskender Laht, also now in Istanbul, see Alexander the Great).

The sculpted lid appears to have been made from a single piece of marble, and the head has the typical features of Archaic herms, including the three rows of curls and the long tresses. The finely carved face has the look of late Archaic Greek sculpture, even if the large ears have been placed rather awkwardly, more in the Egyptian style.

If the dating of this sculpture is correct, then it actually predates the building of the Propylaia of the Athens Acropolis (437-432 BC), and the Classical period of Greek art. |

|

|

| |

Herm from the village of Barzica, Varna District,

Bulgaria. 2nd - 3rd century AD.

Varna Archaeological Museum, Bulgaria. |

Maps, photos and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request. |

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

|