|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English >

People > Ancient Greek artists> Sculptors E-H |

| MFP People |

Ancient Greek artists – page 3 |

|

Page 3 of 14 |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors E - H |

| |

| E G H |

|

| |

A fragmentary marble statue of a woman, described by the museum

as "a distinguished Eleian", from Olympia. On the front of the base

is the inscribed signature of the sculptor Eleuseinios the Athenian

(Ἐλευσείνιος Αθηναίος, see photo below).

2nd half of the 1st century AD. One of three signed honorary portrait statues of ladies from

Elis found in the Heraion in Olympia: another headless statue is signed on the left knee by

Eros (Inv. No. Λ 140; inscription IvO 647), and a statue of the Large Herculaneum Woman

type is signed on the right knee by Aulos Sextos Eraton (Inv. No. Λ 139; inscription IvO 647).

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 141. |

| |

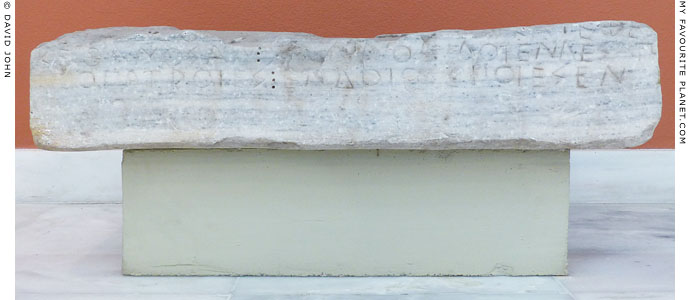

The inscribed signature on the front of the statue base above:

Ἐλευσείνιος Ἀθηναῖος̣

ἐποίει.

Eleuseinios the Athenian

made it.

Inscription IvO 645 |

| |

Endoios

Ἔνδοιος (Latin, Endoeus)

Mid-late 6th century BC

Athens, perhaps an immigrant from Ionia

Pausanias mentioned a statue of seated Athena by Endoios on the Athens Acropolis, dedicated by Kallias (around 564 BC), thought to be the Athenian aristocrat and opponent of the tyrant Peisistratos mentioned by Herodotus (Histories, Book 6, chapter 121). He does not specify the location of the statue, mentioning it only in passing, between an exposition on statues near the south wall of the Acropolis and a description of the Erchtheion at the north side.

"Endoeus was an Athenian by birth and a pupil of Daedalus, who also, when Daedalus was in exile because of the death of Calos, followed him to Crete. Made by him is a statue of Athena seated, with an inscription that Callias dedicated the image, but Endoeus made it."

Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 26, section 4.

A marble statue of seated Athena, found in 1821 below the Erechtheion on the North Slope of the Athens Acropolis and dated around 525 BC, is believed by some scholars to be the work by Endoios mentioned by Pausanias; it has even been named the "Endoios Athena" (see photo and drawing below). The fragmentary, badly worn figure, wearing a long chiton (tunic), is missing its head, forearms and hands, but is recognizable as Athena from the Aegis (with holes for the attachment of bronze snakes around the edge) over her shoulders and the Gorgoneion (see Medusa) on her breast. It is earliest extant identifiable statue of Athena from Athens, perhaps depicting the goddess as Athena Ergane (Ἐργάνη, the Worker), who originally held a distaff and spindle. Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. Acr. 625. Height (including plinth) 147 cm.

A number of early western travellers in Greece, including Richard Chandler, Edward Dodwell and Sir William Gell, reported seeing a statue standing in a wall near what is now known as the "Mycenaean Fountain" on the North Slope of the Acropolis. Chandler, who saw it in 1765, thought it depicted Isis, and Dodwell merely noted seeing "a headless female statue of white marble, sitting on a thronos. It is headless, and much ruined". However, Gell, who travelled around Greece three times between 1801 and 1812 (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 13), recognized it as "a very ancient statue of Minerva", and made a drawing of it appearing much as it does today, built into a late Roman wall thought to have been constructed using spolia around 270-300 AD, around the same time as the Beulé Gate.

See: Patricia A. Marx, Acropolis 625 (Endoios Athena) and the rediscovery of its findspot. Hesperia, Volume 70, No. 2 (April - June 2001), pages 221-254. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA). At jstor.org. |

|

|

| |

It is thought unlikely that this Endoios was a contemporary of the legendary Daidalos, but perhaps the statue was made in what was considered a primitive style, comparable to the "Daedalic style" of the 7th century BC (see the Daidalos page). Dipoenos and Skyllis, sculptors of the early 6th century BC, were also described by Pausanias as "pupils" or "sons" of Daidalos (see above). The "Endoios Athena" in the Acropolis Museum, however, is not Daedalic. It seems that both Pausanias and Pliny the Elder believed that works by Endoios were very ancient, but the Late Archaic sculptor discussed by modern scholars was working just a couple of generations before the advent of the Classical period.

Pausanias ascribed to Endoios a colossal wooden cult statue of Athena Polias in her temple in Erythrai (Ἐρυθραί), Ionia (north of Çeşme, western Turkey), and marble statues of the Graces and the Seasons outside the temple:

"There is also in Erythrae a temple of Athena Polias and a huge wooden image of her sitting on a throne; she holds a distaff in either hand and wears a firmament on her head. That this image is the work of Endoeus we inferred, among other signs, from the workmanship, and especially from the white marble images of Graces and Seasons that stand in the open before the entrance."

Description of Greece, Book 7, chapter 5, section 9.

According to Pausanias (Book 8, chapter 45, section 4 - chapter 47, section 3), a sculptor named Endoios made the ivory cult statue of Athena Alea and the colossal tusks of the Kalydonian Boar for the temple of the goddess in Tegea (Τεγέα), Arcadia, which were later taken to Rome by Augustus and set up in the Forum of Augustus. However, he also mentioned that the sanctuary of Athena Alea had been "utterly destroyed by a fire" (395/394 BC), and that Skopas designed the new temple, thought to have been built 345-335 BC (after the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus). Either the statue and the tusks had survived the fire, or were made by a later artist of the same name, or else the attribution of the works to Endoios may have been myth-making/propaganda.

Pliny the Elder expressed doubt concerning a report by the Roman politician Mucianus that the cult statue in the temple of Artemis in Ephesus was made of vine wood by Endoios, and noted that all other writers said the statue was made of ebony:

"It is believed that ebony lasts an extremely long time, and also cypress and cedar, a clear verdict about all timbers being given in the temple of Diana at Ephesus, inasmuch as though the whole of Asia was building it it took 120 years [CXX annis] to complete, it is agreed that its roof is made of beams of cedar.

But as to the actual statue of the goddess there is some dispute, all the other writers saying that it is made of ebony, but one of the people who have most recently seen it and written about it, Mucianus, who was three times consul, states that it is made of the wood of the vine, and has never been altered although the temple has been restored seven times; and that this material was chosen by Endoeus – Mucianus actually specifies the name of the artist, which for my part I think surprising, as he assigns to the statue an antiquity that makes it older than not only Father Liber [Dionysus] but Minerva [Athena] also.

He adds that nard is poured into it through a number of apertures so that the chemical properties of the liquid may nourish the wood and keep the joins together – as to these indeed I am rather surprised that there should be any – and that the folding doors are made of cypress wood, and the whole of the timber looks like new wood after having lasted nearly 400 years [CCCC prope annis]. It is also worth noting that the doors were kept for four years in a frame of glue. Cypress was chosen for them because it is the one kind of wood which beyond all others retains its polish in the best condition for all time."

Pliny, Natural history, Book 16, chapter 79.

The Archaic Temple of Artemis, completed around 550 BC, was was destroyed by a fire in 356 BC. Its replacement was finally completed in early 3rd century BC. The surviving Roman period statues of Artemis Ephesia are thought to be copies of the cult statue, the original form of which may even predate the arrival of the Greeks in the area. As in the case of Tegea, the attribution to Endoios may have been local propaganda.

The marble base of a grave relief, found in the Plaka, Athens and dated around 525-500 BC, is inscribed in Ionic lettering with an elegiac couplet for a foreign woman named Lampito and the signature of Endoios. Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 10643 (see photo below).

An inscribed pillar that supported a lost votive sculpture dedicated by "Ops----" (perhaps Ophsios or Opsiades) on the Athens Acropolis, around 530-520 BC, signed by Endoios and Philergos (Work-lover or Energetic), thought to be Samian sculptor who worked in Endoios’ workshop. Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6249. The base has been associated with a fragmentary kore in the Acropolis Museum, Inv. No. Acr. 602, which is stylistically similar to the "Endoios Athena". Height 66 cm.

The "Rayet head" of a kouros from Athens, about 520 BC, now in Copenhagen, has been associated with fragments of a kouros from the Piraeus Gate and a base with the signatures of Endoios and Philergos found nearby. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Inv. No. 418. Height 31.5 cm.

The "Neilonides base", a rectangular marble base of a funerary kouros statue, around 530-520 BC, inscribed with a metrical epitaph for the deceased Neilonides and signed by Endoios, was discovered in 1922 by the Greek archaeologist Alexandros Philadelpheus built into the Themistoklean Wall, southwest of the Dipylos, Kerameikos. The front side of the base has two inscriptions in the Attic alphabet, the dedication and the signature Ε [ν] δοιος κ [α] ὶ τόνδ ἐπόε, written vertically. Both were deliberately erased, perhaps at the time they were built into the wall. On the inscribed front are the faint remains of a painting of a seated male figure, perhaps representing Neilonides, his father Neilon or the god Hades (Plouton). It has been suggested that the painting may be by Endoios himself. Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 12870. Inscription IG I(3) 1214.

See: Catherine M. Keesling, Endoios's painting from the Themistoklean Wall: A reconstruction. Hesperia, Volume 68, No. 4 (October - December 1999), pages 509-548. American School of Classical Studies at Athens. At Georgetown University Library, Washington DC.

The "Potter's Relief", a marble votive relief of a potter, shown in profile sitting on a diphros (δίφρος, stool) and holding two kylikes in his left hand, was found on the Athens Acropolis and dated around 520-510 BC. The damaged and now incomplete inscription (IG I(3) 764), is thought to include the signature of Endoios and a dedication by Pamphaios or Euphronios, both names of potters known to have been working in Athens around this time. The signature has been speculatively restored as Ἐν [δοιος εποιεσ] εν. Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. Acr. 1332. Height 122 cm.

It has been suggested that a fragmentary signature on the shield of one of the Giants on the Gigantomachy from the north frieze of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi is that of Endoios. However, the inscription, like that on the "Potter's Relief", was altered in Antiquity, and the sculptor's name is almost entirely lost. The north and east friezes have also been controversially attributed to his contemporary Aristion of Paros (see the Aristion of Paros page). |

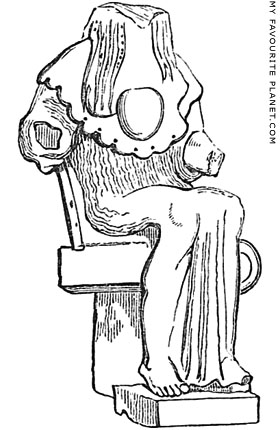

The "Endoios Athena", a marble statue

of seated Athena wearing the aegis

and Gorgoneion on her breast.

Around 525 BC. Attributed to Endoios.

Found in 1821 below the Erechtheion

on the North Slope of the Athens

Acropolis. Insular marble.

Height including the plinth 147 cm.

Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. Acr. 625.

Photo © Konstanze Gundudis |

| |

The "Endoios Athena" statue,

after a drawing made by the artist

George Scharf in Athens in 1840.

Source: A. S. Murray, A history of Greek sculpture, from the earliest times down

to the age of Pheidias, fig. 35, page 197.

John Murray, London, 1880.

Original drawing, British Museum,

Inv. No. 2011,5012.55.

Scharf, who later became the director

of the National Portrait Gallery, London,

also travelled through Lycia with the

archaeologist Charles Fellows in 1840.

See A brief history of Kastellorizo. |

| |

| |

A marble base of a funerary relief for a foreign woman named Lampito, inscribed

with an elegiac couplet and the signature of the sculptor Endoios on three lines.

Around 525-500 BC. Excavated in 1835 by the German archaeologist

Ludwig Ross, ephor of antiquities, in a stairway in the Plaka, Athens,

although it may have been discovered as early as 1830. Pentelic marble.

Height 14 cm, length 176 cm, depth 29 cm.

Most of the top line and the middle of the second line, including much

of the deceased's name ("Lampito"), have been destroyed, and a number

of attempts have been made to restore the dedication. Here is one version:

ἐ̣[νθά]δε Φ̣ι̣— — — —ος κατ̣έθε-

κε θανο͂σαν ⋮ Λ[αμπι]τὸ αἰδοίεν γε͂ς ἀπ-

πατροΐες. ⋮ Ἔνδοιος ἐποίεσεν.

Here lies buried the dead L[ampi]to,

an honorable woman, far from her

homeland. Endoios made [it].

Inscription IG I² 978 (also IG I(3) 1380).

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 10643.

See: Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer (Inscriptions of Greek sculptors),

No. 8, pages 11-12. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

Epigonos of Pergamon

Ἐπίγονος Χαρίου Περγαμηνὸς (Epigonos son of Charios of Pergamon); Latin, Epigonus

Working in Pergamon, 3rd century BC

New article in preparation. |

|

|

| |

Euphranor of Corinth

(also known as Euphranor of Isthmos)

Ἐυφράνωρ (the one who delights, from ευφραίνω, to delight)

Sculptor, painter and theorist, who wrote treatises on symmetry and colours.

From Corinth, he worked mostly in Athens around 390-325 BC.

He was a contemporary of the sculptors Lysippos, Praxiteles and Silanion, and the father of the sculptor Sostratos.

A confusing passage in Pliny the Elder's Natural History (Book 35, chapter 36) has been variously interpreted to mean that he was a pupil either of Aristeides of Thebes (Aristeides II) or Ariston, one of his sons. Other scholars believe that the teacher was actually Aristeides' grandfather, Aristeides I.

See, for example: Katherine Jex-Blake and Eugenie Sellers, The elder Pliny's chapters on the history of art, page 144, note 5. Macmillan & Co., London, 1896.

Pliny called him Euphranor of the Isthmus (Euphranor Isthmius), and placed the height of his career in the 104th Olympiad (364 BC), along with the painter Cydias (of Kythnos ?). His pupils included the painters Antidotus (teacher of Nikias of Athens) and Charmantides (Natural History, Book 35, chapter 40).

As a sculptor in bronze, he is named along with Praxiteles, during the 104th Olympiad (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19).

It has been pointed out by some modern scholars that the chronology of Pliny's account of Euphranor is confused, and that there may have been two artists with this name, one possibly the grandfather of the other.

See:

Olga Palagia, Euphranor. Brill, Leiden, 1980.

Andrew Stewart, Two Independents: Euphranor and Silanion, in One Hundred Greek Sculptors, Their Careers and Extant Works. At Perseus Digital Library.

The Roman rhetorician Quintilian (Marcus Fabius Quintilianus, circa 35-100 AD) saw an evolution in technique and aesthetic quality in Greek painting, reaching its most advanced state in the works of Apelles and other painters from the time of Alexander the Great. In one passage he compared a number of renowned Greek painters including Euphranor. A little later in the same chapter he compared the talents of his hero, the orator Cicero, to those of Euphranor.

"Euphranor, on the other hand, was admired on the ground that, while he ranked with the most eminent masters of other arts, he at the same time achieved marvellous skill in the arts of sculpture and painting."

"But in Cicero we have one who is not, like Euphranor, merely distinguished in a number of different forms of art, but is supreme in all the different qualities which are praised in each individual orator."

Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, Book 12, chapter 10, sections 6 and 12. At Perseus Digital Library. See the entire passage about Greek painters (sections 3-6) on the Painters page.

Pliny the Elder mentioned a number of bronze statues by Euphranor:

"The statue of Alexander Paris [the Trojan prince] is the work of Euphranor: it is much admired, because we recognize in it, at the same moment, all these characteristics; we see him as the umpire between the goddesses [the Judgement of Paris], the paramour of Helen, and yet the slayer of Achilles.

We have a Minerva [Athena], too, by Euphranor, at Rome, known as the 'Catulina', and dedicated below the Capitol, by Q. Lutatius [Q. Lutatius Catulus]; also a figure of Good Success [Bonus Eventus], holding in the right hand a patera, and in the left an ear of corn and a poppy. There is also a Latona [Leto] by him, in the Temple of Concord, with the new-born infants Apollo and Diana in her arms.

He also executed some brazen chariots with four and two horses, and a Cliduchus of beautiful proportions; as also two colossal statues, one representing Virtue, the other Greece; and a figure of a female lost in wonder and adoration: with statues of Alexander and Philip in chariots with four horses."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pliny also included Euphranor in his account of painters, adding that as a sculptor he had made colossal statues as well as sculptures in marble and reliefs on drinking vessels. His work was highly detailed, with particular attention to symmetry, and the heads of his statues were smaller in porportion to the bodies. Statues by other Hellenistic sculptors such as Lysippos were also said to have had proportionally smaller heads in order to create the illusion that the figures were larger than they actually were.

"... in the hundred and fourth Olympiad [364 BC], Euphranor, the Isthmian, distinguished himself far beyond all others, an artist who has been already mentioned in our account of the statuaries. He executed some colossal figures also, and some statues in marble, and he chased some drinking-vessels; being studious and laborious in the highest degree, excellent in every branch, and at all times equal to himself.

This artist seems to have been the first to represent heroes with becoming dignity, and to have paid particular attention to symmetry. Still, however, in the generality of instances, he has made the body slight in proportion to the head and limbs. He composed some treatises also upon symmetry and colours.

His works [paintings] are, an Equestrian Combat; the Twelve Gods; and a Theseus; with reference to which he remarked that the Theseus of Parrhasius had been fed upon roses, but his own upon beef. There are also at Ephesus some famous pictures by him; an Ulysses, in his feigned madness, yoking together an ox and a horse; Men, in an attitude of meditation, wearing the pallium [perhaps philosophers]; and a Warrior, sheathing his sword."

(Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 35, chapter 40. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

The Equestrian Combat, the Twelve Gods, and the Theseus mentioned by Pliny are probably the paintings by Euphranor seen by Pausanias in the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios in the Athens Agora (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 3, sections 3-4). Pliny's "Equestrian Combat" would then be the cavalry fight during the second Battle of Mantinea (362 BC), a copy of which Pausanias also saw in Mantinea in Arcadia (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 8).

"Here is a picture of the exploit, near Mantinea, of the Athenians who were sent to help the Lacedaemonians. Xenophon among others has written a history of the whole war — the taking of the Cadmea, the defeat of the Lacedaemonians at Leuctra, how the Boeotians invaded the Peloponnesus, and the contingent sent to the Lacedacmonians from the Athenians. In the picture is a cavalry battle, in which the most famous men are, among the Athenians, Grylus the son of Xenophon, and in the Boeotian cavalry, Epaminondas the Theban.

These pictures were painted for the Athenians by Euphranor, and he also wrought the Apollo surnamed Patrous [Paternal] in the temple hard by. And in front of the temple is one Apollo made by Leochares; the other Apollo, called Averter of evil [Ἀλεξίκακος, Alexikakos], was made by Calamis. They say that the god received this name because by an oracle from Delphi he stayed the pestilence which afflicted the Athenians at the time of the Peloponnesian War."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 3, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Part of a headless marble statue of a robed Apollo, discovered in 1907 near the remains of the small Ionic temple of Apollo Patroos (2nd half of the 4th century BC), south of the Stoa of Zeus in the Athens Agora, has been tentatively identified as the work by Euphranor (see photo, right). Apollo's epiphet Patroos (Ἀπόλλωνα Πατρῷον, Paternal Apollo) is due to the myth in which he was the father of Ion, founder of the Ionian Greeks, including the Athenians. See also Kalamis and Leochares.

For images of the Twelve Olympian Gods (the Dodekatheon, Δωδεκάθεον), see Dionysus and Demeter and Persephone part 2. Pausanias commented that the painting of "Theseus, Democracy and Demos" represented the popular legend that Theseus introduced democracy to Athens.

A statue of Hephaistos by Euphranor is mentioned in an oration (or discourse) previously believed to have been written by Dio Chrysostom, but now attributed to Favorinus. Dio Chrysostom, Discourse 37 (The Corinthian Oration), chapter 43. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius.

Euphranor and his works were also mentioned by several other ancient authors, including Valerius Maximus, Juvenal, Plutarch, Lucian and Philostratos.

Several paintings and sculptures in museums, mostly Roman copies, have been associated with Euphranor.

The "Antikythera Youth", a bronze statue of a god or hero (see photo below).

A Classicistic bronze statue of Artemis, found in Piraeus and dated to the mid 4th century BC, has been attributed to Euphranor (see photos below). Piraeus Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 4647.

The bronze "Piraeus Athena" statue. Piraeus Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 4646. Also the marble "Athena Mattei", Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. MA 530.

The "Alexander Rondanini" marble statue, thought to represent Alexander the Great and to be part of a Roman period copy of the bronze statue group by Euphranor, mentioned by Pliny (Book 34, chapter 19), depicting King Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander in four-horse chariots. Glyptothek, Munich. Inv. No. GL 298.

Head of Alexander the Great. Pentelic marble. 2nd century AD "copy after a Greek original from the late 4th century BC", also attributed to Euphranor, from the same reference by Pliny. Barracco Museum, Rome. Inv. No. MB 157.78.

Several extant Roman period sculptures are thought to be replicas of a statue of Paris by Euphranor. See, for example, a marble head in Hamburg. |

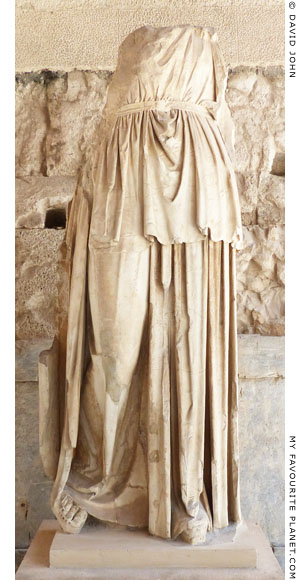

Part of a marble statue of Apollo Patroos, believed to be the cult statue made by Euphranor, mentioned by Pausanias. The

figure probably originally held a kithara.

4th century BC. Found in 1907 around

20 metres south of Temple Patroos in

the Ancient Agora, Athens. Present

height (above plinth) 254 cm.

Exhibited in the lower colonnade of the

Stoa of Attalus, Agora Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. S 2154.

Transferred from the National

Archaeological Museum in 1956. |

| |

A marble statuette from the Athenian

Agora. The standing figure, now

headless, wears a long chiton

belted at the waist and a himation,

and holds a kithara (?) in the left

hand. Identified as Apollo Patroos,

and thought to be a copy of the cult

statue by Euphranor.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 877. |

| |

| |

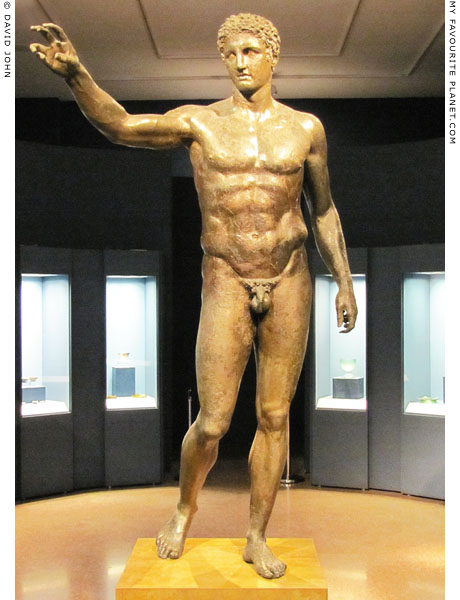

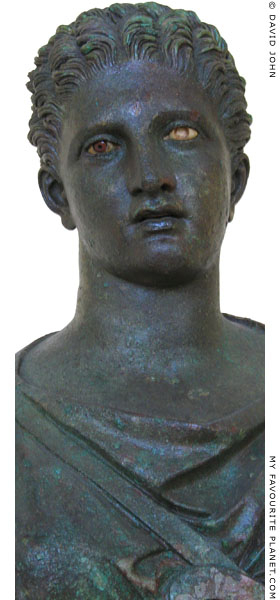

The "Antikythera Youth", also known as the "Antikythera Ephebe"

(Έφηβος των Αντικυθήρων), a bronze statue of a god or hero.

Paris holding the Golden Apple of Discord in his raised right

hand or Perseus holding the severed head of Medusa are

among the many suggested identifications.

Around 340-330 BC. Cast in separate parts, it was probably

made in a Peloponnesian workshop. Euphranor is among those

suggested as the sculptor. Found in 1900 by sponge divers in

the ancient Antikythera shipwreck (see note in Medusa part 1).

It has since been restored twice. Height 194 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. X 13396. |

| |

|

|

|

Bronze statue known as the "Large Artemis", a Late Classical work attributed

to Euphranor or his school, or a northeast Peloponnesian workshop.

Circa 340-330 BC. Excavated in Piraeus in 1959, found with a cache of statues, including

another statue of Artemis (the "Small Artemis", Inv. No. 4648), the "Piraeus Apollo"

(Inv. No. 4645) and the "Piraeus Athena" (Inv. No. 4646). They were probably part of a

shipment intended for Rome which was caught up in the sack of Piraeus by Sulla in 86 BC.

The figure has been identified as Artemis due to an attachment on the back, thought

to be for a quiver (as in the "Small Artemis"), and the position of the fingers of her left

hand which held a bow. The figure wears cross-bands over a peplos. Height 195 cm.

Piraeus Archaeological Museum, Greece. Inv. No. MP 4647.

See also the bronze "Piraeus Athena" statue. Piraeus Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 4646. |

|

| |

Euphron of Paros

Εὔφρων Πάριος

Early - mid 5th century BC; working around 470-450 BC.

From Paros, he worked in Athens and was a contemporary of Kritios and Nesiotes.

Euphron is thought to have made votive reliefs. His signature has been found on several statue pedestals, including two marble votive pillar monuments from the Athens Acropolis, circa 470-450 BC.

A dedication by Phaidros son of Prothymides from Kephale (Κεφαλή), a deme of east Attica.

Φαῖδρο[ς] Προθυ[μίδο]

Κεφαλε͂θεν ἀνέθ[εκ]εν.

Εὔφρον ἐποίε[σ]εν.

Phaidros son of Prothymides

from Kephale dedicated this.

Euphron made it.

Inscription IG I³ 856 at The Packard Humanities Institute (also IG I² 525; Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 304. Acropolis Museum (?).

Fragments of a Pentelic marble pillar monument, dedicated to Athena by a woman named Mikythe (Μικύθη). The dedication is written in Ionian dialect. Found in 1889 near the South Wall of the Athens Acropolis. Height 60 cm.

[Μ]ικύθη μ’ ἀνέ[θηκεν]

[Ἀθ]ηναίηι τό[δ’ ἄγαλμα] /

[εὐξ]αμένη̣ δ̣[εκάτην]

[καὶ] ὑ̣πὲρ πα[ίδων]

[κ]αὶ ἑαυτῆ̣[ς].

Εὔφρων̣ [ἐπο]-

[ί]ησεν̣.

Mikythe dedicated me to Athena, this statue, having vowed a tithe, both on behalf of her children and of herself.

Euphron made it.

Inscription IG I³ 857 at The Packard Humanities Institute (also IG I² 524; CEG 1.273; Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 298). Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6254.

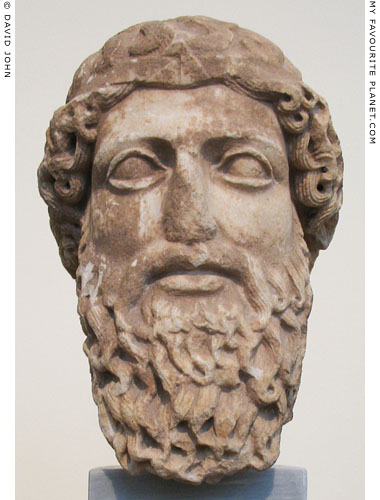

Euphron may have made a bearded head of Pentelic marble (see photo below), dated 450-440 BC, found in 1886 in a sanctuary of Eetioneia in Piraeus. The head, thought to depict a god, either Hermes or Zeus, may belong to an inscribed herm base, also of Pentelic marble, found near it and six large marble altars. Dedicated to Hermes by Python of Abdera (Πύθων Ἀβδηρίτης), Thrace, who appears to have travelled widely, the herm base is signed by Euphron of Paros (see drawing below).

Πύθων Ἑρμῆι ἄγαλμα Ἑρμοστρά-

το Ἀβδηρίτης / ἔστησεμ πολλὰς

θησάμενος πόληας. ∶/ Εὔφρων ἐ-

ξεποίησ’ οὐκ ἀδαὴς Πάριος.

Python son of Hermostratos of Abdera set up for Hermes the object of delight after gazing upon many cities.

Euphron fashioned it, not unskilled, from Paros.

Inscription IG I³ 1018 at The Packard Humanities Institute (also CEG 316; IG I² 826).

Height 44.5 cm, width 55 cm, depth 48 cm. Piraeus Archaeological Museum.

A mutilated base, probably from a funerary monument, found in the ruins of Agios Ioannis church on the island of Nisyros, is also said to be signed by Euphron of Paros.

Εὔφρον ἐποίε Πάριος.

Euphron of Paros made it.

See: Beazley Archive, Artists' Signatures Database, No. 319 |

|

|

| |

A marble head of a bearded god, thought to be

either Hermes or Zeus. Perhaps from a herm

dedicated by Python from Abdera, Thrace,

a work of the Parian sculptor Euphron.

450-440 BC. Pentelic marble. Found in 1886

in a sanctuary of Eetioneia in Piraeus, Greece.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 332. |

| |

A drawing the inscription on the herm base dedicated to Hermes

by Python of Abdera and signed by Euphron of Paros.

Source: Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer (Inscriptions of Greek sculptors),

No. 48, pages 38-39. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

Euthykartides

Ευθυκαρτίδης

Around 650-600 BC

From Naxos

Euthykartides is known only from an inscribed signature on a marble statue base, dated to around 650-600 BC, found in Delos in 1885. Delos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. A 728.

ευθυκαρτιδες ⋮ μ´α ⋮ νεθεκε ⋮ ηο Ναησιοσ ⋮ ποιεσας

(Euthykartides m'anetheke ho nahsios poiesas)

Euthykartides the Naxian dedicated me, having made [me].

Inscription IG XII 5, 2.

It is one of the earliest surviving signatures of a Greek sculptor. Part of a kouros statue also in the Delos museum (Inv. No. A 4052) may belong to the base.

See photos of the base and kouros in Medusa part 2.

See:

Jeffrey M. Hurwit, Artists and signatures in ancient Greece, pages 3-10. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Euthykartides' feet: Reflections on signatures, status, and originality in Greek art. Video of a lecture by Jeffrey Hurwit at the Athens Centre, Athens, on 23th July 2013. At Youtube. |

|

|

| |

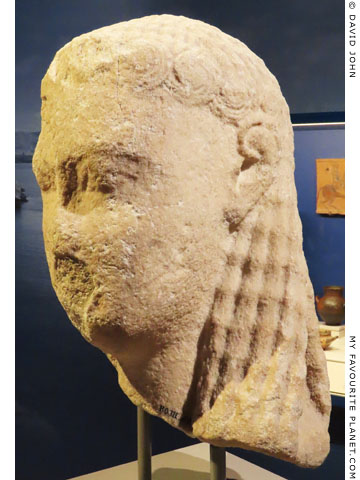

Head of an Archaic kouros statue of Naxian marble

found on Thera (Santorini), Greece.

Around 615-590 BC.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands.

Acquired in 1826 by Colonel B. E. A. Rottiers, who found it in

a fountain. A hole had been drilled from the back and through

the mouth so that it could be used as a water spout. |

| |

Euthykrates

Ευθυκράτης (Latin, Euthycrates)

Late 4th - early 3rd century BC

From Sikyon, northeastern Peloponnese

Accordng to Pliny the Elder, Euthykrates, Laippus and Boedas were the three sons and pupils of Lysippos. He included Euthycrates and Laippus as sculptors in bronze in the time of the 121st Olympiad [296 BC], along with Eutychides (also from Sikyon and a pupil of Lysippus), Cephisodotus (Kephisodotos the Younger), Timarchus and Pyromachus (Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19).

"Laippus" may be an error, meant to be Daippus, who is mentioned later in the same chapter. A Daippos (Δάιππος) is mentioned by Pausanias as the maker of statues of two athletes at Olympia (Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 12, section 6 and chapter 16, section 5).

Also in the same chapter, Pliny mentioned a statue of "a figure in adoration." by Boedas. He also wrote that Euthykrates was the teacher of Tisikrates, also from Sikyon, and that either Euthykrates or Tisikrates taught Xenocrates, a prolific sculptor and author of treatises on sculpture.

Lysippus left three sons, who were also his pupils, and became celebrated as artists, Laippus, Boedas, and, more particularly, Euthycrates; though this last-named artist rivalled his father in precision rather than in elegance, and preferred scrupulous correctness to gracefulness. Nothing can be more expressive than his Hercules at Delphi, his Alexander, his Hunter at Thespiae, and his Equestrian Combat. Equally good, too, are his statue of Trophonius, erected in the oracular cave of that divinity [at Livadia, Boeotia], his numerous chariots, his Horse with the Panniers, and his hounds."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

The clause dealing with a portrait of Alexander the Great ("itaque optume expressit herculem delphis et alexandrum thespiis venatorem et proelium equestre...") has also been translated as "his Alexander Hunting, at Thespiae...". This has beeen considered to refer to a bronze portrait or statue group of Alexander hunting, dedicated at Thespiai in Boeotia after the king’s death. |

|

|

| |

Eutychides of Sikyon

Εὐτυχίδης Σικυώνιος (Eutykhides Sikyonios)

Late 4th - early 3rd century BC

From Sikyon, northeastern Peloponnese

Pliny the Elder included Eutychides among sculptors in bronze in the time of the 121st Olympiad (296-293 BC), with Euthycrates and Laippus (sons of Lysippos), Cephisodotus (Kephisodotos the Younger), Timarchus and Pyromachus (Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19).

Pausanias named Eutychides of Sikyon as a pupil of Lysippos (Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 2, section 7). He also wrote that Eutychides was the teacher of the sculptor Kantharos of Sikyon (Κάνθαρος Σικυώνιος), son of Alexis (Ἀλέξις) (Book 6, chapter 3, section 6). The signature of Kantharos has been found on a pedestal at Thebes.

Pliny the Elder mentioned a bronze statue by Eutychides of the personification of the river Eurotas, Lakonia, Peloponnese.The sculpture had presumably been taken to Rome.

"Eutychides executed an emblematic figure of the Eurotas, of which it has been frequently remarked, that the work of the artist appears more flowing than the waters even of the river."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

The footnotes to this edition mention that "there is a gem still in existence on which this design of Eutychides is engraved".

Pliny noted a marble statue of Dionysus among the artworks displayed in the memorial buildings of Asinius Pollio in Rome.

"In the same place, too, there is a Father Liber [Dionysus], by Eutychides, highly praised."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

He is thought to have been referring to the same Eutychides when mentioning a painting of Nike driving a two-horse chariot.

"Of Eutychides, there is a Victory [Nike] guiding a chariot drawn by two horses."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 35, chapter 40. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias wrote that Eutychides of Sikyon made a statue of Timosthenes of Elis, winner of the boys' foot race at Olympia, and a statue of Tyche for Antioch on the Orontes (Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου) in Syria (today Antakya, Turkey).

"By the statue of Thrasybulus stands Timosthenes of Elis, winner of the foot-race for boys... made by Eutychides of Sicyon, a pupil of Lysippus. This Eutychides made for the Syrians on the Orontes an image of Fortune [Tyche], which is highly valued by the natives."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 2, sections 6-7. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

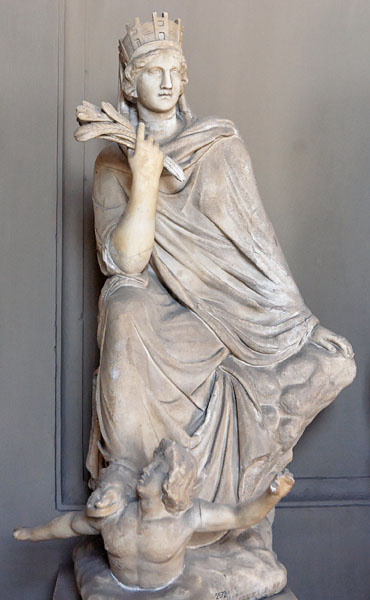

"Tyche of Antioch", a Roman period marble statue, perhaps a copy

of the Hellenistic bronze original by Eutychides. Height 96 cm.

Galleria dei Candelabri, Vatican Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 2672.

Photo by Jastrow at Wikimedia Commons. |

| |

The goddess, wearing a mural crown and a himation (cloak), is seated on a rock, perhaps Mount Silpios (Σιλπίος Όρος) beneath which Antioch on the Orontes was built. Her right foot rests on the right shoulder of a swimming figure, thought to be a personification of the River Orontes (Ὀρόντης).

Pausanias did not describe the Tyche at Antioch, but it is thought to have been a colossal bronze cult statue of Tyche (Τύχη; known to the Romans as Fortuna) as the tutelary spirit and patron or guardian of the city, and that it became a prototype for statues of the goddess in other Hellenistic cities in the Seleucid controlled region of Syria and the Levant. Although there is no direct evidence, it is thought that Eutychides made it soon after the city was founded around 300 BC by Seleukos I Nikator, a general and successor of Alexander the Great, and the founder of the Seleucid dynasty (see History of Pergamon).

According to the Byzantine chronicler John Malalas (Ἰωάννης Μαλάλας, circa 491-578 AD, a native of Antioch), the model for the bronze statue was a young virgin named Aimathe, who Seleukos sacrificed when he laid out the foundations of his new capital. Malalas emphasized the speed with which Seleukos made preparations for the building of the city, which included the sacrfice and the statue, as well as the building of walls by the architect Xenaeus (perhaps Xenarios, Χεναρίος).

"He [Seleukos] laid the foundations of the city at the bottom of the valley opposite the mountain [Silpios], by the great river Dracon which was renamed Orontes, where there was a village called Bottia, opposite Iopolis. After Amphion, the high priest, had sacrificed a virgin girl called Aemathe between the city and the river, Seleucus [founded the city] on the 22nd day of the month of Artemisius which is also May, at the first hour of the day as the sun was rising, and he called the city Antioch, after the name of his son Antiochus Soter.

He immediately started to build a temple, which he dedicated to Zeus Bottius, and he erected imposing walls, designed by the architect Xenaeus. He set up a bronze statue of the slaughtered girl as Tyche in the city above the river, and immediately made a sacrifice to Tyche."

Johannes Malalas, Chronicle, Book 8, sections 200-201. At attalus.org.

The "Tyche of Antioch" in the Vatican and a number of Roman period bronze statuettes, including one from ancient Antaradus (today Tartus, Syria), now in the Louvre, are believed to be copies of the type created by Eutychides.

However, later "Tyche of Antioch" type statues may have been modelled on a gilded bronze statue that John Malalas wrote was set up by Emperor Trajan in the theatre of Antioch, which was completed during his restoration of the city following a severe earthquake in 115 AD. The great devastation caused by the earthquake was described by Cassius Dio (Roman History, Book 68, chapter 24, at LacusCurtius), who also wrote that Trajan was spending the winter in Antioch when it struck. The Hellenistic Tyche statue may have been badly damaged or even destroyed by the quake, and Trajan's new statue, perhaps a restoration or copy of the older sculpture, was shown on coins of Antioch from the reign of Trajan's successor Hadrian. The female figure was shown seated above the river Orontes in the attitude of the Tyche of the city, being crowned by Seleukos I and his son Antiochus I Soter. Once again, Malalas said that a young virgin (in this case named Calliope) was sacrificed prior to the dedication of the statue by Trajan.

"And he [Trajan] completed the theatre of Antioch, which was unfinished, setting up in it, on top of four small pillars in the middle of the nymphaion of the proscenion, a gilded bronze stele of the maiden sacrificed by him. She was sitting over the river Orontes, depicted as the Tyche of the city being crowned by the kings Seleucus and Antiochus."

Johannes Malalas, Chronicle, Book 13, chapter 9.

The several instances of "Tyche sacrifice" mentioned by Malalas are thought to be fictions invented in the 4th century AD as part of a campaign of anti-pagan, pro-Christian (and pro-Constantine) propaganda in the form of "polemical history".

See: Benjamin Garstad, The Tyche sacrifices in John Malalas: Virgin sacrifice and fourth-century polemical history. Illinois Classical Studies 30 (2005), pages 83-136. At academia.edu. |

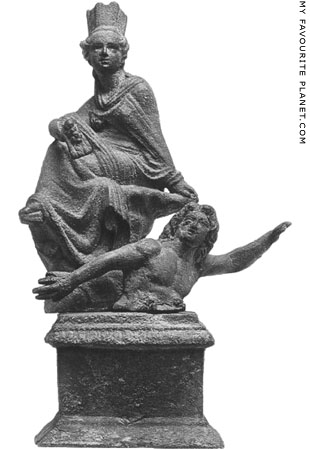

A bronze statuette group of Tyche

of Antioch and the swimming Orontes

River. Perhaps after the Hellenistic

bronze statue by Eutychides.

1st century BC. From Tartus, Syria (ancient

Tortose, Antarados). Total height 16.5 cm,

height of Tyche 11.7 cm, height of Orontes

4.2 cm, height of base 4.8 cm, total width

11.3 cm, total depth 6.7 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. Br 4453. Accession No. MNE 29.

From the collection of Louis De Clercq,

donated in 1967 to the Louvre by Henri

Louis de Boisgelin, his nephew and heir.

Image: monochrome rotogravure by Paul Dujardin. In: Anton de Ridder, Collections

de Clercq, Tome III, Les bronzes,

No. 326, page 228 and planche LI.

Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1905. At Gallica,

Bibliothèque nationale de France. |

| |

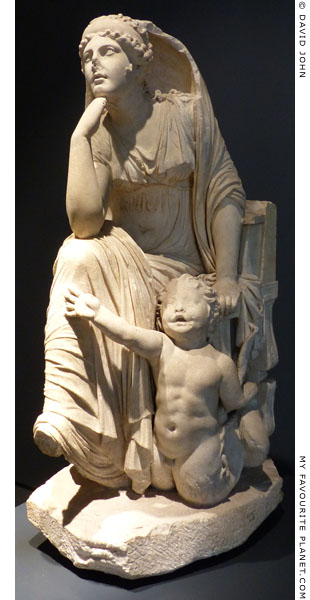

A marble statue of an enthroned female

deity with an infant Triton. Perhaps Thetis,

mother of Achilles, or Amphitrite, wife of

Poseidon. A Roman Imperial period work

thought to have been inspired by the

"Tyche of Antioch" by Eutychides.

2nd century AD. Found 1941 in a residential

building on Via Marsala, near the Termini

railway station, Rome. Greek island marble.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National

Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 121987. |

| |

| |

Evandros of Veroea

Εὔανδρος, Euandros

Also referred to as Evander of Veroea

Second half of the 1st century BC

From Veroea (Βέροια), Macedonia

He was the son of Evandros of Veroea, and possibly the father of Adymos of Veroea.

It is thought that Evandros and Adymos belonged to a family of sculptors who undertook commissions around Macedonia and Thessaly. They both made grave monuments and, unusually, signed their name on them; most sculptors of the time remain anonymous. This suggests that they had a high reputation in the region. |

|

The remains of two grave monuments with reliefs signed by Evandros have been discovered in northern Greece.

See further information and photos

on the Evandros of Veroea page. |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors |

G |

|

|

|

| |

Glaukias of Aegina

Γλαυκίας (Latin, Glaucias)

From Aegina, early 5th century BC

At Olympia Glaukias of Aegina made a bronze chariot and a portrait statue of "Gelon of Gela, son of Deinomenes", who won a victory in the 73rd Olympic Games (488 BC). This is usually taken to be, Gelon, the tyrant of Sicily, but Pausanias had his doubts:

"As regards the chariot of Gelon, I did not come to the same opinion about it as my predecessors, who hold that the chariot is an offering of the Gelon who became tyrant in Sicily. Now there is an inscription on the chariot that it was dedicated by Gelon of Gela, son of Deinomenes, and the date of the victory of this Gelon is the seventy third Festival.

But the Gelon who was tyrant of Sicily took possession of Syracuse when Hybrilides was archon at Athens, in the second year of the seventy second Olympiad [491 BC], when Tisicrates of Croton won the foot-race. Plainly, therefore, he would have announced himself as of Syracuse, not Gela. The fact is that this Gelon must be a private person, of the same name as the tyrant, whose father had the same name as the tyrant's father. It was Glaucias of Aegina who made both the chariot and the portrait statue of Gelon."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 9, section 4-5).

Parts of the base of this sculpture group were discovered in April 1878 and May 1884 in the north part of the Palaistra, Olympia. The three large blocks of Parian marble, dated around 488-485 BC, each around 26 cm high and 82-84 cm wide, are inscribed along the front with Gelon's dedication and the signature of Glaukias.

[Γέλων Δεινομένεος Γελῷ]ος ⋮ ἀνέθεκε.

Γλαυκίας ⋮ Αἰγινάτας ⋮ ἐ[π]οίεσε.

Gelon of Gela, son of Deinomenes, dedicated it.

Glaukias of Aegina made it.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. Nos. 382a (a b), 382b (c). Inscription IvO 143.

Around two decades later Onatas and Kalamis were to make bronze statues to commemorate the Olympic victories of Gelon's brother and successor Hieron I (see Onatas).

Glaukia also made a statue of Philon (Φίλων) from Korkyra (Κόρκυρα, Corfu), who won the Olympic boxing championship twice.

"By the side of the chariot of Gelon is dedicated a statue of Philon, the work of the Aeginetan Glaucias. About this Philon Simonides the son of Leoprepes composed a very neat elegiac couplet:

'My fatherland is Corcyra, and my name is Philon; I am

The son of Glaucus, and I won two Olympic victories for boxing.'"

Pausanias, Book 6, chapter 9, section 9.

As Pausanias continued his description of Olympia, he reported bronze statues of the boxer Glaukos of Karystos (ὁ Καρύστιος Γλαῦκος, Book 6, chapter 10, sections 1-3) and the "great Theagenes" of Thasos (Θεαγένης ὁ Θάσιος, Book 6, chapter 11), who won several victories in boxing, the pankration and long-distance running at the Olympic Games and other games around Greece. Earlier (Book 6, chapter 6, section 5), Pausanias had mentioned Theagenes' boxing victory at the 75th Olympic Games (480 BC). The whole of chapter 11 is devoted to anecdotes concerning the life and career of Theagenes, including several miraculous tales involving statues. |

|

|

| |

Glaukos of Argos

Γλαῦκος (Latin, Glaucus)

From Argos, mid 5th century BC.

Glaukos of Argos worked with Dionysios of Argos to make several statues at Olympia for Mikythos, the former tyrant of Rhegion (see the note in Homer part 1). Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 26. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Glaukos of Chios

Γλαῦκος (Latin, Glaucus)

Metalworker from the eastern Aegean island of Chios (Χίος), working around 700 BC or later.

Herodotus wrote that Glaukos of Chios made a large silver krater (κρητῆρα, bowl or vessel for mixing wine and water) on a welded iron stand (ὑποκρητηρίδιον), given by the Lydian king Alyattes II (ruled circa 617-560 BC) as a votive offering to the oracular sanctuary of Pythian Apollo at Delphi. The historian also credited Glaukos with the invention of welding iron (σιδήρου κόλλησις, literally the sticking together of iron; not soldering).

"Alyattes the Lydian, his war with the Milesians finished, died after a reign of fifty-seven years. He was the second of his family to make an offering to Delphi (after recovering from his illness) of a great silver bowl on a stand of welded iron. Among all the offerings at Delphi, this is the most worth seeing, and is the work of Glaucus the Chian, the only one of all men who discovered how to weld iron."

Herodotus, The Histories, Book 1, chapter 25. At Perseus Digital Library.

Some scholars have read this passage to mean that Glaukos made only the stand, and that the bowl may have been made by another artist. This offering was probably "most worth seeing" among the many others at Delphi for more than just the impressive size of the silver bowl, as other large objects of precious materials are also said to have been given to Delphi by Lydian kings. The bowl and stand may have been richly decorated with engravings or reliefs, like many of the surviving parts of Archaic bronze cauldrons and tripod stands found at Greek sanctuaries (see for example Medusa page 2).

A number of later authors also mentioned the stand and bowl, appearing to have known about them from the passage by Herodotus. By the time Pausanias visited Delphi in the mid 2nd century AD, the krater (κρατῆρος) had disappeared and only the stand (ὑπόθημα) of Alyattes' offering remained.

"Of the offerings sent by the Lydian kings I found nothing remaining except the iron stand of the bowl of Alyattes. This is the work of Glaucus the Chian, the man who discovered how to weld iron. Each plate of the stand is fastened to another, not by bolts or rivets, but by the welding, which is the only thing that fastens and holds together the iron.

The shape of the stand is very like that of a tower, wider at the bottom and rising to a narrow top. Each side of the stand is not solid throughout, but the iron cross-strips are placed like the rungs of a ladder. The upright iron plates are turned outwards at the top, so forming a seat for the bowl."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 16, sections 1-2. At Perseus Digital Library.

Athenaeus of Naucratis (early 3rd century AD, see note on Ephesus gallery 1, page 22), citing Herodotus and a lost treatise on art by Hegesandros of Delphi (2nd century BC or later), also wrote that the iron stand was by Glaukos of Chios. He also claimed to have seen the stand at Delphi, and part of his description of its reliefs has survived:

"And Hegesander the Delphian, in his book entitled A Commentary on Statues and Images, says that the pedestal dedicated by Glaucus the Chian at Delphi is like an iron ἐγγυθήκη, the gift of Alyattes. And that is mentioned by Herodotus, who calls it ὑποκρητηρίδιον (a stand for a goblet). And Hegesander uses the same expression. And we ourselves have seen that lying at Delphi, a thing really worth looking at, on account of the figures of animals which are carved upon it, and of other insects, and living things, and plants . . . . . . can be put upon it, and goblets, and other furniture."

Athenaeus of Naucratis, The Deipnosophists, (Banquet of the learned), translated by C. D. Yonge, Volume 1 (of 3), Book 5, chapter 45 (page 334). Henry G. Bohn, London, 1854. At Project Gutenberg.

Plutarch (circa 46-120 AD), who was a priest at Delphi, also cited Herodotus' report on the offering of Alyattes, but did not mention the name of the artist.

"Observe first how it is with the artists. Take as our first example the far-famed stand and base for the mixing-bowl here which Herodotus has styled the 'bowl-holder'; it came to have as its material causes fire and steel and softening by means of fire and tempering by means of water, without which there is no expedient by which this work could be produced; But art and reason supplied for it the more dominant principle which set all these in motion and operated through them."

Plutarch, On the failure of oracles (Περὶ τῶν Ἐκλελοιπότων Χρηστηρίων; Latin, De defectu oraculorum), chapter 47. In: Plutarch, Moralia, Volume 5, Loeb Classical Library edition, 1936. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius.

The Chronicle of Eusebius of Caesarea (written circa 311 AD), as translated into Latin by Saint Jerome around 380 AD, dated the invention of iron welding by Glaukos to the fourth year of the 21st Olympiad (693/692 BC). This date is over half a century before the birth of Alyattes, and it has therefore been suggested by modern scholars that the iron base may have been made long before he sent it to Delphi. As a venerable welded artwork (perhaps the first) by the inventor of the technique himself it may have been considered a dedication of greater value.

"Glaucus Chius primus ferri inter se glutinum excogitavit."

"Glaucus of Chios first figured out how to stick iron to itself."

Jerome, Chronicle, Part 1, in Latin (Hieronymi, Chronicon) and English. At The Tertullian Project, edited by Roger Pearse.

Glaukos was recorded as the maker in Ethnica by Stephanus of Byzantium (Στέφανος Βυζάντιος, 6th century AD), citing Herodotus and Polybius (Πολύβιος, circa 200-118 BC), wrote that there were two artists named Glaukos: one, the maker of the stand at Delphi, was from Samos; the other, a renowned sculptor, was from Lemnos.

"Πολύβιος δ' ἐν τριακοστῇ τετάρτῃ λέγει Αἰθάλειαν τὴν Λῆμνον καλεῖσθαι, ἀφ' ἧς ἦν ὁ Γλαῦκος, εἷς τῶν τὴν κόλλησιν σιδήρου εὑρόντων· δύο γὰρ ἦσαν. οὗτος μὲν Σάμιος, ὅστις καὶ ἔργον ἀοιδιμώτατον ἀνέθηκεν ἐν Δελφοῖς, ὡς Ἡρόδοτος, ὁ δ' ἕτερος Λήμνιος, ἀνδριαντοποιὸς διάσημος."

"Polybios, on the other hand, says in the thirty-fourth book (34,11,4) that Aithaleia [Αἰθάλεια] is (the island) Lemnos, the home of Glaukos, one of those who invented the welding of iron. There were actually two of them: one was a Samian who also set up a very famous dedication at Delphi, as Herodotus reported (1,25,2); and the other, a Lemnian, was a well-known sculptor."

Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica (Εθνικά; epitome by Hermolaus, Ερμόλαος).

Greek text: section § A46.6, Αἰθάλη (Aithali), at ToposText.

Most of Book 34 of Polybios' Histories is lost, its content is known only from fragments cited by later authors. The section in Ethnica concerns Aithale (Αἰθάλη, fume) the ancient Greek name for the Italian island Elba, which Stephanus thought was due to the fact that iron ore was worked there. He compared this to Aithaleia (Αἰθάλεια), an ancient name for the northern Aeagean island Lemnos (Λῆμνος). The Thracian island was sacred to Hephaistos, the god of metalworkers and sculptors, and it is thought that several artists, particularly of the Samian school of sculptors, worked there.

It has thus been suggested that Glaukos of Chios may have been a member of the Samian school, and also that he may have worked on Lemnos. On the other hand it has also been suggested that there has been a muddle in which Glaukos the inventor of welding has become two or more sculptors of the same name, or that a number of artists have been conflated into one. Another suggestion is that Glaukos the sculptor may have been confused with the writer and grammarian Glaukos of Samos.

The earliest known use of the ancient Greek phrase "Γλαύκου τέχνη" (Glaukon techne, the skill or art of Glaukos) is in Plato's dialogue Phaedo (section 108d at Perseus Digital Library). It apparently became a proverb and its origin and significance have been discussed by scholars since antiquity. Some have believed that it may have referred to the Chian iron welder, the Samian author or some other Glaukos, historical or mythical.

For a comprehensive collection of comments on this proverb by ancient and Medieval authors, see:

An incomplete history of the proverb "Glaukos' skill" at Sententiaeantiquae |

|

|

| |

Glaukos of Samos

and

Glaukos of Lemnos

From the Aegean islands of Samos (Σάμος) and Lemnos (Λῆμνος), dates unknown.

Glaukos of Lemnos was mentioned only by Stephanus of Byzantium in the same passage as Glaukos "the Samian", the inventor of iron welding (otherwise known as Glaukos of Chios). |

|

|

| |

Glykon of Athens

Γλύκων Ἀθηναῖος

Late 2nd - early 3rd century AD

Nothing is known abour Glykon apart from an inscribed signature on the colossal "Farnese Hercules" statue in Naples: Γλύκων Ἀθηναῖοc ἐποίει (Glykon of Athens made it; the sigma (Σ) of Athinaios is rendered as C).

The statue, also known as "Hercules at rest" or the "Weary Herakles", was found in 1546 in the Baths of Caracalla, Rome. The work of the late 2nd - early 3rd century AD is thought to be a copy of a Greek bronze original perhaps made around 325 BC by Lysippos or one of his circle. Glykon may therefore have been one of many copyists making reproductions of Greek works for the Roman market. Copyists' workshops are known to have existed at places such as Baiae in the Bay of Naples.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6001.

Inscription IG XIV 1238 (IGUR IV 1556). |

|

|

| |

|

|

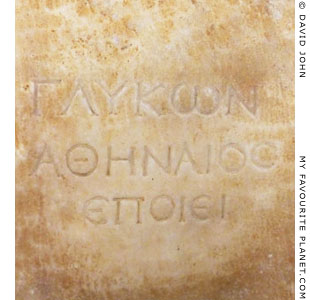

The signature of Glykon of Athens,

inscribed in Greek on the side of

the rock on which Herakles leans:

Γλύκων Ἀθηναῖοc ἐποίει

Glykon of Athens made it

The sigma (Σ) of Athinaios is rendered as C.

Inscription IG XIV 1238 (IGUR IV 1556). |

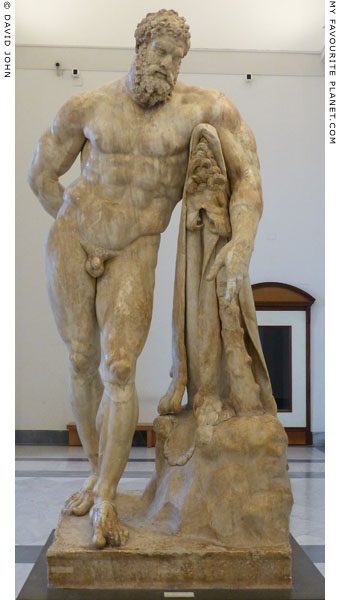

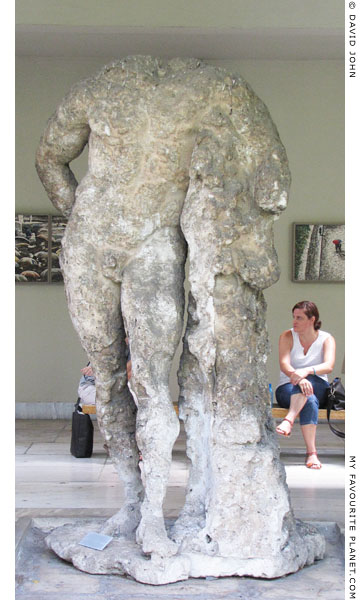

The "Farnese Hercules", a colossal marble statue of Herakles,

also known as "Hercules at rest" or the "Weary Herakles".

Late 2nd - early 3rd century AD Roman Imperial period. Thought to be a copy of

a Greek bronze original made around 325 BC by Lysippos or one of his circle.

Found in 1546 in the Baths of Caracalla, Rome. Height 3.17 metres.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 6001. Farnese Collection.

|

|

Probably the most famous, and certainly the largest surviving ancient statue of Herakles, which gave its name to the numerous Farnese type statues and statuettes. Many of the surviving examples were made during the Roman Imperial period, but depictions of the semi-divine hero in this pose are known to have been made from the early Hellenistic period (see photos below). They are thought to have been derived from a bronze statue by Lysippos or one of his circle, made around 325 BC.

Other types of statues of "Hercules at rest" have also been attributed to Lysippos. They usually depict Herakles standing with his right arm resting on his club, and the skin of the Nemean Lion hanging from his lower left arm. But none are as expressive or powerful as the Farnese Hercules.

Ironically, the famous statue depicts Herakles not as an indefatigable super-hero at a moment of action or triumph, but as a tired, slumping, aging man. Looking care-worn and exhausted, the massively-built, naked figure of Herakles, leans on a tree trunk (or column) on top of a rock over which he has draped the skin of the Nemean Lion. His leaning post was cleverly designed by the sculptor to support the enormous mass of the leaning figure. The hero's legs are also arranged one in front of the other (as though he is about to stride on to further adventures), spaced to distribute the weight of the marble statue. With his lowered left hand he holds onto his trademark club which rests on the rock.

The head was deliberately made smaller than it should be in proportion to the entire figure in order to emphasize the size and strength of his exaggeratedly muscular body. The deep furrow across his brow and other wrinkles (for example on his left arm) make it clear that the hero is aging, after many years of travelling the world to undertake his enormous labours.

One of his twelve labours was to obtain the Golden Apples of Hesperides, which he holds in his right hand, behind his back (see photo, right). The apples are his guarantee of immortality and the renewal of his youth and strength.

Following its discovery in 1546, the statue became part of the large art collection (the Farnese Collection) of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, grandson of Pope Paul III. It was placed beside another statue found at the Baths of Caracalla, the so-called "Latin Hercules", in the portico of the courtyard of the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. In the 1590s it was moved to its own room, on the walls of which were frescoes depicting the hero's adventures by Annibale Carracci and his studio.

Along with the rest of the Farnese Collection, the statue was moved to Naples by Ferdinand IV of Bourbon in 1787. The move was controversial at the time, as the collection, especially the statue of Hercules, had become an essential part of visits of Rome by tourists and artists.

The left forearm has been restored with plaster. The statue was discovered without legs, and Michelangelo commissioned one of his pupils, the sculptor and architect Guglielmo della Porta (circa 1500-1577), to make some (see photo, right). The original legs were later found and became part of the Borghese Collection, however, because of the taste of the time, della Porta's restorations continued to be preferred until the end of the 18th century. The originals were reintegrated by Carlo Albacini in 1787. Goethe wrote: "It is now impossible to understand how those of della Porta were considered good for so long." Della Porta's legs are now on display in the Naples museum, near the Hercules statue (see photo, right).

The restored parts of the statue had been removed for its transportation from Rome to Naples. Due to the reluctance of Neapolitan restorers to attempt to tackle such a famous work, as well as delays in completing an appropriate room for the museum, it remained in a crate for many years. Napoleon planned to take the statue to Paris, but the members of the regime he had set up in Naples were forced to flee before the shipment could be made. The statue was finally put on display by Michele Arditi, director of the museum 1807-1839.

An earlier sculptor named Glykon is known from a signature on a fragment of an inscribed marble statue base found in Pergamon in 1878. Γλύκω[ν ... ἐποίει] (Glykon made it). Bergama Museum, Inv. No. 1 55. Inscription IvP VIII 2, 391). The sculpture may have been one of the statues mentioned by Tacitus (Annals, 2, 83) as having been erected in honour of Germanicus Caesar at the time of his visit to the area in 18 AD, a year before his death.

See: Max Fränkel (editor), Altertümer von Pergamon, Band VIII, Die Inschriften von Pergamon, 2: Römische Zeit - Inschriften auf Thon, No. 391, page 279-280. W. Spemann, Berlin, 1895. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

The right hand of the Farnese Hercules,

held behind his back with the wrist

resting on the top of his right buttock.

In his curled fingers he holds three

of the Golden Apples of Hesperides. |

| |

Hercules' legs by Guglielmo della Porta.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. |

| |

| |

A painting of Herakles as a child, his torso leaning slighly to the right. He holds

the skin of the Nemean Lion under his left arm, and in his left hand his club

which rests on a rock. Behind his shoulders are what appear to be wings.

From the side of one of two marble funerary couches in the

Macedonian tomb of Potidaia, Halkidiki, Macedonia. Around 300 BC.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum.

|

| The tomb, 2.75 metres long, 3 metres wide and 3.3 metres high, had a simple Doric facade with two pillars and a pediment, and covered with white plaster. The walls of the vaulted main chamber were covered with painted decoration. When discovered, each of the couches, set at right angles to one another, had a skeleton lying on it. Along the side of each couch are similar small colour sketches of deities and animals. |

|

|

| |

A larger than lifesize marble statue of Herakles

of the Farnese type. From the Antikythera

shipwreck (see note in Medusa part 1).

Late Hellenistic copy of a bronze original thought

to have been made by Lysippos or one of his circle

around 325 BC. Parian marble. Height 238 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. 5742. |

|

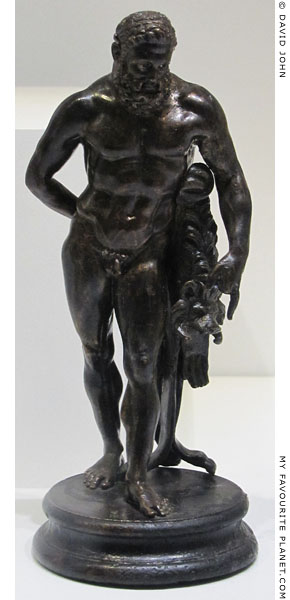

A bronze statuette of Herakles at rest

from Pergamon. One of several extant

copies of the "Farnese Hercules" type.

Late 1st century BC. Found in

one of the terrace houses on

the Pergamon acropolis.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

Gorgias

Γοργίας

Working in Athens, late 6th century BC

Perhaps from Sparta (Laconia)

Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19) mentioned "Gorgias the Laconian" (Gorgias Lacon), along with Agelades (Ageladas of Argos) and Callon, as sculptors working in bronze in the 87th Olympiad (432 BC). However, a number of signatures by Gorgias found on statue bases in Athens, all dedications set up on Acropolis, are dated to the last quarter of 6th century BC. Of these three, perhaps four, supported marble statues.

See a marble statue base from the Athens Acropolis, inscribed with the signature of Gorgias below. |

|

|

| |

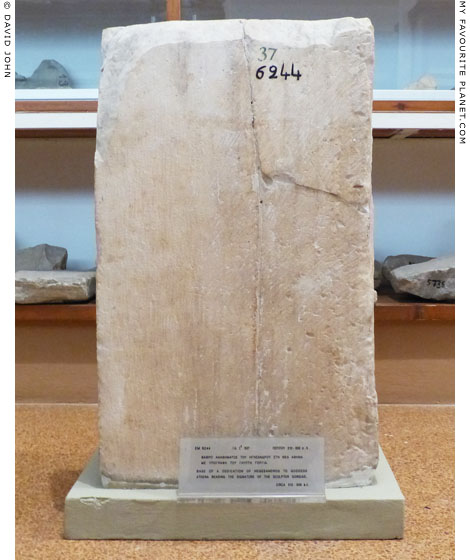

Part of a marble statue base inscribed with a dedication by

Hegesandros to Athena and the signature of the sculptor Gorgias.

The base, restored from a number of fragments, supported a

statuette, perhaps of a horse or a horse and rider.

Around 510-500 BC. Fragments found between 1877 and 1886

on the Athens Acropolis, east of the Erechtheion. Pentelic marble.

Ἑγέσαν[δρος]

ἀ̣νέθεκ̣[εν]

τἀθεναίαι.

[Γ]οργίας : ἐπο[ίεσεν].

Hegesandros

dedicated [it]

To Athena.

Gorgias made [it].

Inscription IG I³ 637 (also IG I² 490; Antony E. Raubitschek,

Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 65).

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6244. |

| |

| Sculptors |

H |

|

|

|

| |

Hegesias

Ἡγησίας

5th century BC

It has been suggested that there may have been as many as three sculptors named Hegesias, while some scholars consider him to be the same person as Hegias of Athens. |

|

See Hegias of Athens below. |

|

| |

Hegias of Athens or Hegesias

Hegias (Ἑγίας or Ἡγίας) or Hegesias (Ἡγησίας)

From Athens, Early 5th century BC, working in bronze around 490-460 BC

Hegias may have been the teacher of Pheidias (see Pheidias for further details).

Hegias is mentioned by Pausanias and Pliny the Elder, while Hegesias is mentioned by Quintilian, Lucian of Samosata and Pliny. It has been suggested that there may have been as many as three sculptors named Hegesias, while other scholars consider him to be the same person as Hegias.

Pausanias wrote that Hegias of Athens was a contemporary of Onatas of Aegina and Ageladas of Argos, both thought to be working in the early 5th century BC.

"Onatas was contemporary with Hegias of Athens and Ageladas of Argos."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 42, section 10. At Perseus Digital Library.

Hegesias was mentioned by Quintilian (Marcus Fabius Quintilianus, circa 35-100 AD), who described the works of Kallon (probably Kallon of Aegina, late 6th - early 5th century BC) and Hegesias as crude and stiff:

"The art of Callon and Hegesias is somewhat rude and recalls the Etruscans..."

Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, Book 12, chapter 10 (see the full quote under Kalamis 1).

Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανὸς ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, circa 125 - after 180 AD) mentioned Hegesias along with Kritios and Nesiotes (both early 5th century BC), and his description of their works appears to indicate the Severe style of early Classical sculpture:

"... the clean-cut, sinewy, hard, firmly outlined productions of Hegesias, or the school of Critius and Nesiotes."

Lucian, The rhetorician’s vade mecum (Ῥητόρων Διδάσκαλος).

Pliny the Elder mentioned Hegias as a sculptor in bronze and a contemporary of Pheidias, Alkamenes, Critias (Kritios) and Nesiotes, in the 83rd Olympiad (448 BC). Later in the same chapter mentioned celebrated works by Hegias and Hegesias.

"Hegias is celebrated for his Minerva [Athena] and his King Pyrrhus, his youthful Celetizontes [κελητιζοντες, boy jockeys], and his statues of Castor and Pollux, before the Temple of Jupiter Tonans [on the Capitoline Hill, Rome]; Hegesias, for his Hercules, which is at our colony of Parium [in Mysia, on the Hellespont]."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19.

As is often the case with Pliny, scholars have seen the text as confused or "suspect", due to errors made either by Pliny himself or by later editors or copyists. Pheidias and Alkamenes have been placed at the same date as Hegias, Kritios and Nesiotes who are thought to have been working a generation earlier. He may have referred to a number of Greek sources when considering the works of Hegias, one or more of which may have named him as Hegesias. Hegias (Ἑγίας or Ἡγίας) is thought to have been an abbreviation or variant of the Ionic and Attic name Hegesias (Ἡγησίας). Agasias (Ἀγησίας, as in Agasias of Ephesus) may have been the Doric version of the name.

The German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) may have been the first to point out the problem concerning Pliny's mention of a statue of King Pyrrhus (Πύρρος) by Hegias. Even by Pliny's own reckoning (e.g. Book 8, chapter 6), King Pyrrhus I of Epirus (319/318-272 BC) lived too late to have been portrayed by the Hegias of the 5th century BC. The statue was perhaps made by a later Hegias or some other artist, or the figure may have been part of a statue group depicting Athena supporting the mythical hero Pyrrhus (also known as Neoptolemos), son of Achilles.

Winckelmann also speculated that the statues of Castor and Pollux at the top of the stairway up to the Capitol (see the Dioskouroi page) were those by Hegias. However, this is considered very doubtful.

Earlier in the same chapter Pliny also mentioned statues of keletizontes by Kanachos (probably Kanachos the Elder).

A bronze horse known as "il Cavallo di Vicolo delle Palme", found in 1849 in Trastevere, Rome, and now in the Capitoline Museums, is thought by some scholars to be part of the Granikos Monument statue group by Lysippos, commissioned by Alexander the Great, while others believe it may be a work of Hegias.

See the signature of Hegias on a marble base from the Athens Acropolis below. |

|

|

| |

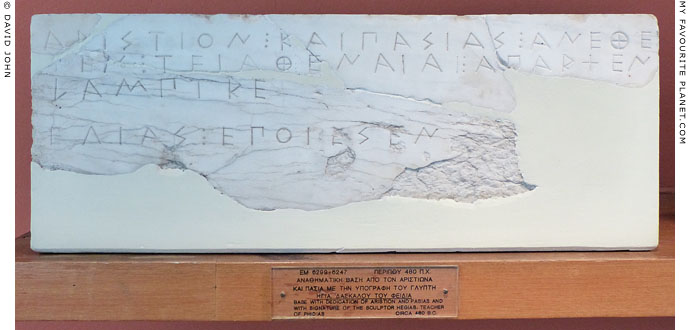

Fragments of a marble base of a bronze statue, inscribed with a dedication by Aristion and Pasias,

and the signature of the sculptor Hegias, thought to be the teacher of Pheidias. The base shows

signs of damage by fire, which perhaps occurred during the Persian sack of Athens in 480 BC. *

Around 500-475 BC. From the Athens Acropolis.

Ἀριστίον ⋮ καὶ Πασίας ⋮ ἀνεθέ-

τεν ⋮ τε͂ι Ἀθεναίαι ⋮ ἀπαρχὲν

Λαμπτρε͂.

Ἑγίας ⋮ ἐποίεσεν.

Inscription IG I³ 702 (Antony E. Raubitschek,

Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 94).

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. Nos. EM 6299 and EM 6247.

* See: Charles Hill Morgan, Pheidias and Olympia, page 313.

In: Hesperia, Volume 21 (1952), Issue 4, Pages 295-339. At jstor.org. |

| |

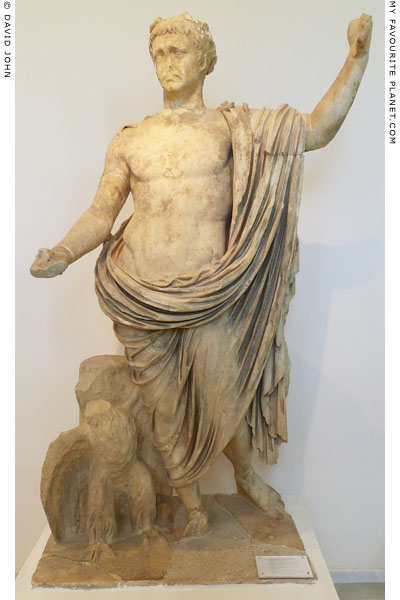

Hegias (Roman period)

Ἡέγίας

Working in Athens in the mid 1st century AD, Roman Imperial period.

This Roman period Hegias is known only from the signature of the sculptors Hegias and Philathenaios, thought to be Athenians, on an over-lifesize marble portrait statue of Emperor Claudius (reigned 41-54 AD) found in the Metroon in Olympia (see photo below). The signature is inscribed on the tree stump supporting the figure's right leg. Made of Pentelic marble, the statue, depicting Claudius as Zeus/Jupiter with a sceptre and an eagle, is thought to have been set up in the Metroon during his lifetime as part of a group of statues for the imperial cult. A similar statue found in Lanuvium (Vatican Museums, Inv. No. 243) indicates that this work was directly inspired by a prototype created in Rome. Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 125.

A Pentelic marble portrait statue of Agrippina Minor, the niece and fourth wife of Claudius (they married in 49 AD), found near the Heraion, is believed to have belonged to the same group of statues which stood in the Metroon. Its plinth is signed by Dionysios, son of Apollonios, also thought to have been from Athens. Olympia Archaeological Museum, Inv. No. Λ 143.

See: Olga Palagia, Sculptures from the Peloponnese in the Roman Imperial period. In: A. D. Rizakis and Cl. E. Lepenioti (editors), Roman Peloponnese III. Society, economy and culture under the Roman Empire: continuity and innovation, pages 432-445. Institute for Greek and Roman Antiquity, The National Hellenic Research Foundation, Athens, 2010.

The article includes three other signatures, those of Eros, Eleuseinios and Aulos Sextos Eraton, all thought to have been working in Athens in the 1st century AD, on Pentelic marble portrait statues of women from the Heraion in Olympia. Also mentioned are Roman period sculptors' signatures from Corinth (Theodotos, an Athenian) and Sparta (Mantikles son of Sosikrates, Antilas son of Ainetidas, Demetrios son of Demetrios, [---] son of Dionysios). |

|

The signature of the sculptors Hegias

and Philathenaios on the tree stump

of the statue of Emperor Claudius

in Olympia (see photo below). |

|

| |

An over-lifesize marble portrait statue of Emperor Claudius

as Zeus/Jupiter. The signature of the sculptors Hegias and

Philathenaios is inscribed at the top of the tree stump

support behind the now headless eagle.

41-54 AD. From the Metroon, Olympia. Pentelic marble.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 125.

Currently exhibited in the Museum of the History

of the Ancient Olympic Games, Olympia. |

| |

Heliodoros (of Rhodes?)

Ἡλιοδωρος (Gift of Helios)

Perhaps from Rhodes; active around 100 BC

Pliny the Elder included an artist named Heliodorus among several who had made bronze statues of "athletes, armed men, hunters, and sacrificers" (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library). He also wrote that a Heliodorus, perhaps the same artist, made a renowned marble statue group of Pan and Olympos (Ὄλυμπος, a famous mythical aulos player, poet and disciple of the Satyr Marsyas) wrestling, which stood in the Porticus Octaviae (Portico of Octavia), Rome.

"The figures of Pan and Olympus Wrestling, in the same place, are by Heliodorus; and they are considered to be the next finest group of this nature in all the world."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Earlier in the same chapter, Pliny had mentioned another highly-valued marble statue group of "Olympus and Pan" (Latin, "olympum et pana") by an unknown artist, which was exhibited in the porticos of the Septa in the Campus Martius, Rome.

"No less is the uncertainty that prevails as to the authors of the statues now to be seen in the Septa; an Olympus and Pan, and a Chiron and Achilles ["chironem cum achille", see Homer part 2]; and yet their high reputation has caused them to be deemed valuable enough for their keepers to be made answerable for their safety at the cost of their lives."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

A number of similar marble statue groups now in various museums and collections, referred to as "Pan and Daphnis", "Pan and Olympos", or even "Pan and Apollo", have been considered by some scholars to be Roman period copies of an original Hellenistic work by Heliodoros, perhaps one of those mentioned by Pliny. See, for example, the statue group of Pan and Daphnis in Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome.

It may seem reasonable to assume that Pliny was referring to the same Heliodoros in both instances, and that the artist came from the island of Rhodes, where the sun god Helios (Ἡλιος) was the patron deity. Several statue bases found on Rhodes, dated to the first half of the 1st century BC, are inscribed with the signature of "Ploutarchos son of Heliodoros of Rhodes".

Πλούταρχος Ἡλιοδώρου Ῥόδιος ἐποίησε.

Examples: IG XII,1 48; IG XII,1 108; IG XII,1 844; AIV 57 (1898) 269,11; AD 18 A (1963) 8,12; Lindos II 131b; Lindos II 131d; Lindos II 197d; Lindos II 287; Lindos II 308; MDAI(A) 21 (1896) 41,8; SEG 39:732; SEG 39:760. |

|

|

| |

Hephaistos

Ἥφαιστος

Mythological

Hephaistos, the son of Zeus and Hera, was the Greek god of metalworkers and sculptors, the archetypal maker of fine and extravagant metal objects, including armour for gods and heroes. He was also the god of fire and volcanoes, his Roman equivalent being Vulcanus. |

|

See the Hephaistos page for further information. |

|

| |

Hermippos

Ἡέρμιππος

Working in Athens around the end of the 6th century BC

Hermippos is not mentioned in ancient literary sources and is known only from his signature on fragments of a statue base found on the Athens Acropolis (see below). |

|

|

| |

Part of a marble statue base inscribed with a dedication by a

woman named Phsakythe and the signature of the sculptor

Hermippos. It originally supported three bronze statuettes.

Probably around 510-500 BC. Two fragments from the Athens Acropolis: the first

found on 22 April 1840, east of the Parthenon; the second found in 1888, near the

southwest corner of the Parthenon. A third, small fragment from the left corner of the

base is now lost. Grey marble. Present height 10 cm, length 44 cm, width 28 cm.

[Φ]σακύθε : ἀνέθεκεν.

ℎέρμιππος : ἐποίεσεν.

Phsakythe dedicated it.

Hermippos made it.

Inscription IG I³ 656 (also IG I² 493; Antony E. Raubitschek,

Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 81).

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6250. |

| |

Herophon of Macedon

Ἡροφῶν Ἀναξαγόρου Μακεδὼν (Herophon, son of Anaxagoras, of Macedon)

From Macedonia, 2nd - 1st centuries BC

Herophon is known from a signature on an inscribed block of light grey limestone which originally stood on top of a large bathron (βάθρον, base) for a statue or statue group. It was found on 24th March 1879 during excavations led by German archaeologist Ernst Curtius (1814-1896), built into the remains of a tower of the "Byzantine Western Wall", to the south of the Zeus Temple at Olympia (see image below).

Ἡροφῶν Ἀναξαγόρου Μακεδὼν ἐποίησε.

Herophon, son of Anaxagoras, of Macedon made it.

Based on the letter forms, the inscription has been dated to the 2nd or 1st century BC. Interestingly, Herophon's home is given as Macedon rather than one of its cities (e.g. Adymos of Veroea or Paionios of Mende). Although his signature has been well preserved, the incomplete two-line inscription in Greek above it is badly weathered, and a number of scholars have found it difficult to decipher the worn lettering. The bathron consisted of several blocks, and the inscription continued across blocks either side of this one. Fragments of the other blocks were found nearby, but none with other parts of the text.