|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English >

People > Ancient Greek artists> Sculptors I-M |

| MFP People |

Ancient Greek artists – page 4 |

|

Page 4 of 14 |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors I - M |

| |

| I K

L M |

|

| |

Iktinos

Ικτίνος (Latin, Ictinus)

Architect and sculptor from Athens, Mid 5th century BC

Iktinos and Kallikrates designed the Parthenon in Athens (Plutarch, Parallel lives, Pericles, chapter 13, section 4).

He was the also architect of the Temple of Apollo at Bassai (Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 41, sections 7-9) and the Telesterion, the temple of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis (Vitruvius, Book 7, Introduction, section 16).

See Iktinos under architects for further information. |

|

|

| |

Iason the Athenian

(also referred to as Jason)

Ιασων Ἀθηναιος

Working in Athens, early 2nd century AD

Known only from his inscribed signature on a Roman period marble statue of the personification of Homer's Odyssey, found in the Athenian Agora. Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 2039.

ΙΑCΩΝ

ΑΘΗΝΑ [Ι

ΟCΕΠΟ

ΕΙ

Jason the Athenian made it

See the article and photos in Homer part 1. |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors |

K |

|

|

|

| |

Kalamis (5th century BC)

Κάλαμις (Latin, Calamis)

A Greek artist named Kalamis was mentioned by a number of ancient authors of the Roman period. Modern scholars believe that these references point to at least two, perhaps three different artists:

Kalamis 1,

a sculptor of the 5th century BC;

Kalamis 2,

a sculptor of the 4th century BC;

Kalamis 3,

an artist working in silver, perhaps Kalamis 2. |

|

For further details, see the Kalamis page. |

|

|

| |

Kallikles

Καλλικλῆς; Latin, Callicles

Mid-late 5th century BC

From Megara (Μέγαρα), central Greece

A contemporary of Pheidias, he was the son of the sculptor Theokosmos of Megara, and perhaps the father of the sculptor Apelleas son of Kallikles. It has been stimated that he may have been working from around 420 BC.

When describing statues of Olympic victors in Olympia, Pausanias, noted the statue by Kallikles of Megara of the men's boxing champion Diagoras (Διαγόρας) of Rhodes, who is thought to have won in the 79th Olympiad (464 BC). We are also told that this Kallikles was the son of the Theokosmos (Θεόκοσμος) who made the statue of Zeus at Megara, mentioned by Pausanias in Book 1 (see Theokosmos of Megara). Given the assumed dates of Kallikles' career, it is thought that the statue may have been made many years after Diagoras' victory.

"When you have looked at these also you will reach the statues of the Rhodian athletes, Diagoras and his family. These were dedicated one after the other in the following order. Acusilaus, who received a crown for boxing in the men's class; Dorieus, the youngest, who won the pancratium at Olympia on three successive occasions. Even before Dorieus, Damagetus beat all those who had entered for the pancratium.

These were brothers, being sons of Diagoras, and by them is set up also a statue of Diagoras himself, who won a victory for boxing in the men's class. The statue of Diagoras was made by the Megarian Callicles, the son of the Theocosmus who made the image of Zeus at Megara."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 7, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

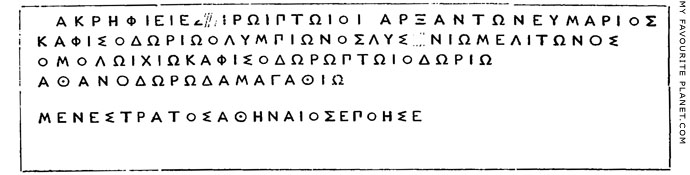

Five small white marble fragments of the inscribed base of the statue of Diagoras were found on 2 December 1880 at the Metroon in Olympia. Inscription IvO 151.

A little further on, Pausanias mentioned the statue of the boy boxer Gnathon (Γνάθων), also made by Kallikles of Megara.

"Next to the sons of Alcaenetus stand Gnathon, a Maenalian of Dipaea, and Lucinus of Elis. These too succeeded in beating the boys at boxing at Olympia. The inscription on his statue says that Gnathon was very young indeed when he won his victory. The artist who made the statue was Callicles of Megara."

Book 6, chapter 7, section 9.

Pliny the Elder mentioned an artist named Callicles among sculptors in bronze who made statues of philosophers.

"Colotes, who assisted Phidias in the Olympian Jupiter, also executed statues of philosophers; the same, too, with Cleon, Cenchramis, Callicles, and Cepis."

Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

It has been argued that this artist may have been Kallikles son of Eunikos, working around 300 BC in Megara, but otherwise known only from a signed base of a bronze portrait statue found there.

See: Felix Bölte, Georg Weicker, Nisaia und Minoa. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band 29, 1904, pages 79–100.

Pliny also wrote that a certain "Callicles also painted some small pictures". This artist was also mentioned by Varro, but is thought to have worked in the second half of the 4th century BC, around the time of Alexander the Great.

Book 35, chapter 37. |

|

|

| |

Kallikrates

Καλλικράτης (Latin, Callicrates)

Architect and sculptor

From Athens, 5th century BC

According to Plutarch (Parallel lives, Pericles, chapter 13, section 4), the only ancient author to mention him, Kallikrates designed the Parthenon with Iktinos, and constructed the middle long wall between Athens and Piraeus during the period of Pericles' political power.

He was the architect of the Ionic Temple of Athena Nike (427-421 BC) on the Athens Acropolis, and perhaps the Ilissos Temple, Athens, thought to be the Temple of Artemis Agrotera (circa 435-430 BC).

Athenian decrees on a marble stele, circa 427-424 BC, concerning the Athena Nike Temple: the selection and payment of the priestess, and the construction of a door for the sanctuary as well as a temple and stone altar to be built according to the specifications of Kallikrates.

Inscription IG I (3) 35. Athens Epigraphical Museum (EM 8116). Now in the Acropolis Museum, Athens.

Pausanias on the temple of Artemis Agrotera, on the Ilissos, Athens: Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book I, chapter 19, section 6.

See also: Ione Mylonas Shear, Kallikrates. Hesperia, Volume 32, No. 4 (October - December 1963), pages 375-424, plates 86-91. American School of Classical Studies at Athens. At jstor.org. |

|

|

| |

|

Kallimachos

Καλλίμαχος (Latin, Callimachus)

Architect, sculptor and perhaps a painter

2nd half of the 5th century BC.

His place of birth is unknown, although Athens and Corinth have been suggested.

He was a contemporary of Agorakritos and Alkamenes.

According to Pliny the Elder, Vitruvius and Pausanias, he was nicknamed Katatexitechnos (Κατατηξιτεχνος, literally, finding fault with one's own craftsmanship; over-meticulous, perfectionist). Pliny also recorded that he was said to have been painter.

"Of all sculptors, though, Callimachus is the most remarkable for his surname: he always deprecated his own work, and made no end of attention to detail, so that he was called the Niggler (Katatexitechnos), a memorable example of the need to limit meticulousness. He made the Laconian Women Dancing, a flawless work, but one in which meticulousness has taken away all charm. He is said also to have been a painter."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias wrote that Kallimachos made a golden lamp with a bronze chimney in the shape of a palm tree for the Erechtheion on the Athens Acropolis (around 409-406), and that he was the first to use the drill in stone sculpture:

"A golden lamp for the goddess [Athena in the Erechtheion] was made by Callimachus. Having filled the lamp with oil, they wait until the same day next year, and the oil is sufficient for the lamp during the interval, although it is alight both day and night. The wick in it is of Carpasian flax [probably asbestos], the only kind of flax which is fire-proof, and a bronze palm above the lamp reaches to the roof and draws off the smoke.

The Callimachus who made the lamp, although not of the first rank of artists, was yet of unparalleled cleverness, so that he was the first to drill holes through stones, and gave himself the title of Refiner of Art [katatexitechnos], or perhaps others gave the title and he adopted it as his."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 26, sections 6-7. At Perseus Digital Library.

Drills were used in stonework long before Kallimachos, but he may have developed more refined drilling techniques for elaborately detailed sculptures.

Pausanias also mentioned that he made a seated statue of Hera Nympheyomen (Νυμφευομένην, the Bride) for the Temple of Hera at Plataia (Πλάταια) in Boeotia, built around 427 BC.

"Here too is another image of Hera; it is seated, and was made by Callimachus. The goddess they call the Bride for the following reason..."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 2, section 7. At Perseus Digital Library.

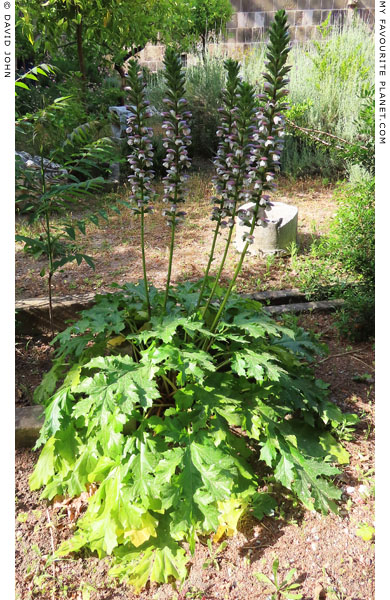

Vitruvius credited with the invention of the Corinthian capital to Kallimachos, who was inspired by a display of acanthus leaves (see photo below).

"It is related that the original discovery of this form of capital was as follows. A freeborn maiden of Corinth, just of marriageable age, was attacked by an illness and passed away. After her burial, her nurse, collecting a few little things which used to give the girl pleasure while she was alive, put them in a basket, carried it to the tomb, and laid it on top thereof, covering it with a roof-tile so that the things might last longer in the open air. This basket happened to be placed just above the root of an acanthus. The acanthus root, pressed down meanwhile though it was by the weight, when springtime came round put forth leaves and stalks in the middle, and the stalks, growing up along the sides of the basket, and pressed out by the corners of the tile through the compulsion of its weight, were forced to bend into volutes at the outer edges.

Just then Callimachus, whom the Athenians called κατατηξίτεχνος for the refinement and delicacy of his artistic work, passed by this tomb and observed the basket with the tender young leaves growing round it. Delighted with the novel style and form, he built some columns after that pattern for the Corinthians, determined their symmetrical proportions, and established from that time forth the rules to be followed in finished works of the Corinthian order."

Vitruvius, Ten books on architecture, Book 4, chapter 1, sections 9-10. At Perseus Digital Library.

A fragmentary inscription (SEG 46 830) of the late 5th - early 4th century BC, found in 1981 in Vergina (ancient Aigai), Macedonia, Greece, appears to refer to Kallimachos. The epigram may be connected with a work by him or even be his funerary inscription. It has been suggested, that like the playwright Euripides, Kallimachos was one of the artists invited to work in Macedonia by King Archelaos (see History of Pella), and that he may have died there.

See: Chrysoula Saatsoglou-Paliadele, ΝΑΩΝ ΕΥΣΤΥΛΩΝ: A fragmentary inscription of the Classical period from Vergina. In: E. Voutyras (editor), Inscriptions of Macedonia, Third International Symposium on Macedonia, Thessaloniki, 8-12 December 1993, pages 101-102. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 1996.

No surviving sculpture can securely by attributed to Kallimachos, although a number of works of the late 5th century BC as well as Roman period copies have been seen as candidates.

Kallimachos may have made some of the reliefs on the balustrade around the Temple of Athena Nike on the Athens Acropolis, circa 427-421 BC.

(See also Paionios of Mende.)

A marble statue of Winged Nike, an akroterion from the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios in the Athenian Agora, has been attributed to Kallimachos. Excavated at the site of the stoa in 1933, it is dated around 400 BC. Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 312.

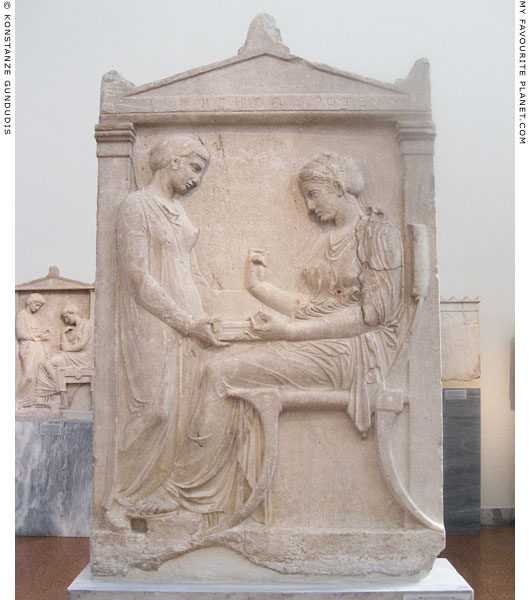

The relief on the marble grave stele of Hegeso, found in the Kerameikos, Athens, and dated to the late 5th century BC has been attributed to Kallimachos (see photo below). National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 3624.

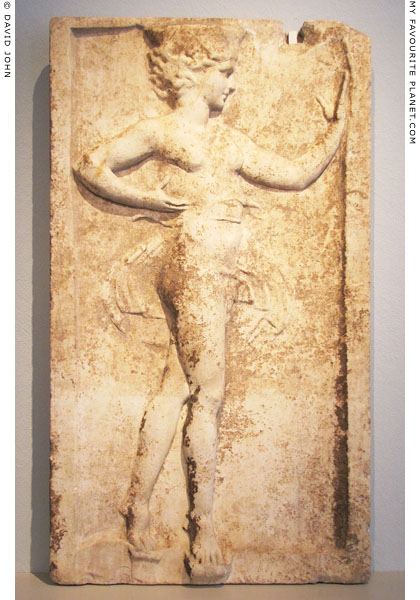

The so-called "Kalathiskos Dancer", a Neo-Attic

marble relief depicting a young dancing woman, 1st century BC, may have been inspired by a work of Kallimachos (see photo below). Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. SK 1456.

A Neo-Attic relief with dancing maenads (Barracco Museum, Rome. Inv. No. MB 124), and other similar reliefs are thought to have been based on the bronze "Laconian Dancers" by Kallimachos mentioned by Pliny the Elder.

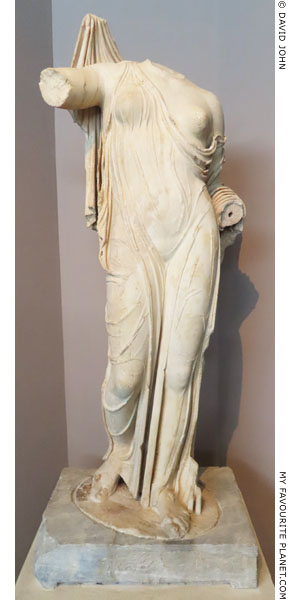

The clinging drapery and other features of works (or copies) attributed to Kallimachos have led to the attribution of the original of the "Venus Genetrix" (or "Aphrodite Fréjus") type marble statues to a hypothetical bronze statue made by him around 420-410 BC. These include a 1st century AD marble statuette of Aphrodite holding an apple (see photo, above right), found in Epidauros. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 1811.

The "Venus Genetrix" type is named due to the belief that the several known examples may be copies of the now-lost cult statue of the Temple of Venus Genetrix (Venus Universal Mother), built by Julius Caesar at the north end of the Forum of Caesar (Forum Iulium or Forum Caesaris), Rome, and consecrated in 46 BC. According to Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 35, chapter 45), Marcus Terentius Varro (116-27 BC) wrote that the statue was made by Arcesilaus (Ἀρκεσίλαος, Arkesilaos).

The "Aphrodite Fréjus", the best example of the type, is dated to late 1st - early 2nd century AD (see photo, right). Thought to have been found in the 17th century at Fréjus, southeastern France, it was originally in the collection of Louis XIV, and is now in the Louvre. Inv. No. Ma 525. Height 1.64 metres.

The statues of the type are thought to depict Aphrodite either as a goddess of vegetation and fertility or a participant in the Judgement of Paris (see Hermes). The goddess stands with her weight on her left leg, her head turned slightly to her left. She wears a himation (cloak) over a thin chiton that clings to her body, and is gathered in pleats between her legs. It hangs from her right shoulder, but the left shoulder and breast are uncovered. With her right hand she draws up the himation, which crosses her back and is draped over her bent left arm. In her outretched left hand she holds an apple. |

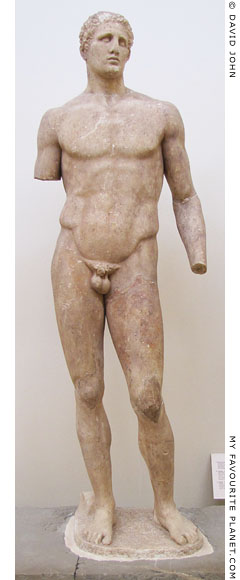

A marble statuette of Aphrodite of the

"Venus Genetrix" type, thought to have

been inspired by a bronze statue made by

Kallimachos around 410 BC (Classical

period). She is depicted either as a

goddess of vegetation and fertility, or as

a participant in the Judgement of Paris

(see Hermes). She wears a long chiton

(tunic), with her left shoulder and breast

bare, and a himation (cloak), an edge of

which she lifts over her right shoulder

with her right hand. In her left hand

she holds out an apple.

1st century AD, Roman Imperial period.

Found in the sanctuary of Apollo Maleatas

(Ἀπόλλων Μαλεάτας), on the slope of

Mount Kynortion, east of the Sanctuary

of Asklepios at Epidauros. Height 55 cm.

The statue has been restored: the head

has been reattached, and the arms and

part of the himation have been restored

with plaster.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 1811. |

| |

A plaster cast of the "Aphrodite Fréjus"

statue, from the original in the Louvre.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam.

Inv. No. 16.078. |

| |

A marble statue of Aphrodite, considered

one of the best surviving examples of the

"Aphrodite Fréjus" or "Louvre-Neapolis"

type statue.

1st - 2nd century AD. From Thessaloniki.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

A flowering acanthus (ἄκανθος, thorn) plant in the garden of the Rhodes Archaeological Museum, planted as a reminder of its connection with the invention of the Corinthian order, attributed by Vitruvius to Kallimachos (see above).

In the Mediterranean area one of the most common of around 30 species of the herbaceous perennial Acanthaceae plant family is Acanthus mollis, also known as bear's breeches, bear's foot plant (in German wahrer Bärenklau, true bear's claw), sea dock, sea holly or oyster plant. This example has reached a height of over 1.5 metres by mid May. |

|

|

|

| |

The marble grave stele of Hegeso, daughter of Proxenos,

with a relief attributed to Kallimachos.

End of the 5th century BC. Found in the ancient cemetery

of the Kerameikos, Athens. Pentelic marble.

The name of the deceased is inscribed on the epistyle of the stele. On the right of the

relief a woman sits on a chair with a footstool, facing left, and looks at a piece of jewellery,

originally painted on the stele, she held in her right hand. On the left, facing her, a young

female attendant (slave), holds open the jewellery box tha rests on the lap of her mistress.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 3624.

Photo: © Konstanze Gundudis |

| |

The so-called "Kalathiskos Dancer", a Neo-Attic marble relief

of a young dancing woman wearing a basket-like headdress

(kalathiskos) and a swirling, transparent chiton.

Thought to have been made in a Neo-Attic workshop in

Athens for the Roman market in the 1st century BC, as

a copy of a Classical original, perhaps by Kallimachos.

Height 95 cm, width 54 cm, depth 10 cm. Relief height 3.5 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. SK 1456.

Acquired in Florence, Italy, in 1892.

See: 2336: Relief mit Kalathiskostänzerin.

Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

At arachne.uni-koeln.de. |

| |

Kallon of Aegina

Καλλον (Latin, Callon)

Late 6th - early 5th century BC

According to Pausanias, he was a pupil of Tectaeus and Angelion, who were pupils of Dipoenos and Skyllis (early 6th century).

Quintilian also mentioned a Kallon and Hegesias (see Hegias of Athens) as examples of earlier sculptors whose work was "somewhat rude and recalls the Etruscans" (Institutio Oratoria, Book 12, chapter 10, sections 7-9; see Kalamis 1).

Only Pausanias specified two sculptors of this name: Kallon of Aegina and Kallon of Elis.

Pausanias wrote that Kallon of Aegina made the cult statue for the temple of Athena at Troezen in the Peloponnese.

"On the citadel is a temple of Athena, called Sthenias. The wooden image itself of the goddess was made by Callon, of Aegina. Callon was a pupil of Tectaeus and Angelion, who made the image of Apollo for the Delians. Angelion and Tectaeus were trained in the school of Dipoenus and Scyllis."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 32, section 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

At Amyklai near Sparta (see Bathykles) he made a bronze tripod, probably decorated with reliefs, beneath which stood a statue of Persephone.

"The things worth seeing in Amyclae include ... There are also bronze tripods. The older ones are said to be a tithe of the Messenian war.

Under the first tripod stood an image of Aphrodite, and under the second an Artemis. The two tripods themselves and the reliefs are the work of Gitiadas [Γιτιάδας, Gitiadas of Sparta, circa 500 BC]. The third was made by Callon of Aegina, and under it stands an image of the Maid [Persephone], daughter of Demeter."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 3, chapter 18, sections 7-8.

(Due to an error in this online translation, the name of Kallon appears as "Gallon", but correctly as Αἰγινήτου Κάλλωνοςin the Greek version.)

The bronze tripods, dedicated as offerings to gods, may have resembled those found at other places such Olympia, which were decorated with several reliefs depicting mythological scenes (see an example on the Medusa page).

Pausanias also noted that he was said to have lived around the same time as Kanachos of Sikyon (the Elder?), and a little earlier than Menaechmus and Soldas of Naupaktos who made a chryselephantine statue of Artemis at Patras.

"Others say that the wrath of Artemis against Oeneus weighed as time went on more lightly [elaphroteron] on the Calydonians, and they believe that this was why the goddess received her surname. The image represents her in the guise of a huntress; it is made of ivory and gold, and the artists were Menaechmus and Soldas of Naupactus, who, it is inferred, lived not much later than Canachus of Sicyon and Callon of Aegina."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 7, chapter 18, Section 10. |

|

|

| |

Kallon of Elis

Καλλον (Latin, Callon)

Around 494-436 BC

From Elis, western Peloponnese.

A Kallon specifically from Elis is only mentioned by Pausanias.

The Kallon mentioned by Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19) as a sculptor working in bronze during 87th Olympiad (430-427 BC), along with Agelades and Gorgias the Laconian (see Gorgias), is believed by some scholars to be Kallon of Elis.

Kallon of Elis made a group of 37 bronze statues at Olympia as a memorial to a chorus of 35 boys, their trainer and flautist from Messine (Μεσσήνη, today Messina), northeastern Sicily, who drowned while crossing the narrow Straits of Messina to Rhegion in southwest Italy.

"On this occasion the Messenians mourned for the loss of the boys, and one of the honours bestowed upon them was the dedication of bronze statues at Olympia, the group including the trainer of the chorus and the flautist. The old inscription declared that the offerings were those of the Messenians at the strait; but afterwards Hippias [around 436 BC], called 'a sage' by the Greeks, composed the elegiac verses on them. The artist of the statues was Callon of Elis."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 25, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Kanachos of Sikyon (the Elder)

Κάναχος (Latin, Canachus)

Late 6th - early 5th century BC.

From Sikyon, northwestern Peloponnese.

There were apparently two sculptors named Kanachos, referred to by modern scholars as the Elder and the Younger (see below). They may have been grandfather and grandson.

Pausanias does not distinguish between them, but writes that a Kanachos made two statues of Apollo (now dated to around 500 BC), and elsewhere of a Kanachos who was a pupil of Polykleitos of Argos who is thought to have been working around 460-420 BC.

Pliny the Elder's several mentions of the name are equally vague. It is uncertain which Kanachos he is referring to when he writes:

"I find it stated that Canachus, an artist highly praised among the statuaries in bronze, executed some works also in marble."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4.

According to Pausanias, the brother of Kanachos (probably the Elder), Aristokles of Sikyon, was also a renowned artist.

"Ptolichus [of Aegina] was a pupil of his father Synnoon, and he of Aristocles the Sicyonian, a brother of Canachus and almost as famous an artist."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 9, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias also named Askaros of Thebes as a pupil of Kanachos of Sikyon. He wrote that Askaros made a statue of Zeus at Olympia for the Thessalians, and was of the opinion that it had been made before the Persian invasion of Greece (480-479 BC).

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 24, section 1.

Cicero, discussing the "systematic development" of sculpture by comparing the works of Kanachos, Kalamis, Myron and Polykleitos, commented that "the figures of Canachus are too stiff and formal to resemble life". Cicero, Brutus, section 70 (see full quote under Kalamis 1).

Statues of three Muses by Aristokles, Kanachos and Ageladas were described in an epigram by the Greek poet Antipater of Sidon (Ἀντίπατρος ὁ Σιδώνιος) in the 2nd century BC (see Ageladas).

Pausanias is thought to have been referring to Kanachos the Elder when describing the cedar wood statue of Apollo he made for the temple of Ismenian Apollo in Thebes, comparing it with his similar bronze statue at the sanctuary of Apollo in Didyma (Δίδυμα), in the territory of Miletus, Ionia.

"On the right of the gate is a hill sacred to Apollo. Both the hill and the god are called Ismenian, as the river Ismenus Rows by the place. First at the entrance are Athena and Hermes, stone figures and named Pronai [Of the fore-temple]. The Hermes is said to have been made by Pheidias, the Athena by Scopas.

The temple is built behind. The image is in size equal to that at Branchidae [Didyma]; and does not differ from it at all in shape. Whoever has seen one of these two images, and learnt who was the artist, does not need much skill to discern, when he looks at the other, that it is a work of Canachus. The only difference is that the image at Branchidae is of bronze, while the Ismenian is of cedar-wood."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 10, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias mentioned the Apollo at Didyma by Kanachos on another occasion, when describing the sanctuary of Aphrodite in Sikyon, for which the artist made the chryselephantine cult statue of the goddess.

"After this is the sanctuary of Aphrodite, into which enter only a female verger, who after her appointment may not have intercourse with a man, and a virgin, called the Bath-bearer, holding her sacred office for a year. All others are wont to behold the goddess from the entrance, and to pray from that place.

The image, which is seated, was made by the Sicyonian Canachus, who also fashioned the Apollo at Didyma of the Milesians, and the Ismenian Apollo for the Thebans. It is made of gold and ivory, having on its head a polos, and carrying in one hand a poppy and in the other an apple."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 10, sections 4-5).

Pliny the Elder also mentioned a bronze statue of Apollo at Didyma by Kanachos, thought to refer to Kanachos the Elder.

"Canachus executed a nude Apollo, which is known as the 'Philesian'. It is at Didymi, and is composed of bronze that was fused at Aegina. He also made a stag with it, so nicely poised on its hoofs, as to admit of a thread being passed beneath. One fore-foots, too, and the alternate hind-foot are so made as firmly to grip the base, the socket being so indented on either side, as to admit of the figure being thrown at pleasure upon alternate feet. Another work of his was the boys known as the 'Celetizontes'."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pliny's description of the stag (or stags) has been described as "difficult" to comprehend or translate, but it is thought that the figure(s) could be mechanically operated.

Pliny also mentioned statues of keletizontes (κελητιζοντες, boy jockeys) by Hegias of Athens.

The Didyma statue of Apollo Philesios (Απολλων Φιλήσιος, The Lovely, or Of the Kiss) by Kanachos is thought to have been cast in Aegina around 500 BC, and to be the figure shown on coins of Miletus and on the so-called "Kanachos Relief" found in the Roman theatre of Miletus (Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Inv. No. Sk 1592; see photo below), as well as a bronze statuette in the British Museum (from Etruria, 1st century BC - 1st century AD, Inv. No. 1824,0405.1. Bronze 209). Coins of Tarsus show a similar type of statue. However, it is not certain whether it was the cult statue of the temple, since the god at Didyma was known as Apollo Dydimeus (Διδυμέυς). It may have been a votive offering for the oracle.

It is thought that the statue may have been among the artworks looted by the Persians, either by Darius I in 494 BC or by Xerxes in 479 BC, and taken to Persia, then returned during the Hellenistic period by Seleucus I Nicator (circa 358-281 BC).

"Xerxes, too, the son of Dareius, the king of Persia, apart from the spoil he carried away from the city of Athens, took besides, as we know, from Brauron the image of Brauronian Artemis, and furthermore, accusing the Milesians of cowardice in a naval engagement against the Athenians in Greek waters, carried away from them the bronze Apollo at Branchidae. This it was to be the lot of Seleucus afterwards to restore to the Milesians."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, Chapter 46, section 3.

"I am persuaded that Seleucus was the most righteous, and in particular the most religious of the kings. Firstly, it was Seleucus who sent back to Branchidae for the Milesians the bronze Apollo that had been carried by Xerxes to Ecbatana in Persia."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, Chapter 16, section 3.

According to Arrian of Nicomedia (2nd century AD), Alexander the Great himself ordered the return of statues looted from the Greeks by Xerxes.

See: Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander, Book 3, chapter 16 and Book 7, chapter 19. At wikisource.

See also: Volker Michael Strocka, Der Apollon des Kanachos in Didyma und der Beginn des strengen Stils. In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Band 117 (2002), pages 81-135 with illustrations. Walter de Gruyter, 2003. At Universitätsbibliothek Freiburg. |

|

|

| |

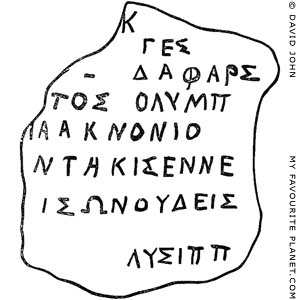

The "Kanachos Relief" thought to depict the Archaic bronze statue of Apollo Philesios, made around

500 BC by Kanachos of Sikyon (the Elder) for the sanctuary of Apollo in Didyma (Δίδυμα), Ionia.

Marble. 150-200 AD, Roman Imperial period. Found in February 1903 in the orchestra

of the Roman theatre of Miletus (Μίλητος, today Balat, Aydin Province, Turkey).

Height 79.5 cm, length 1.90 cm, depth 33 cm.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 1592.

|

| The stiff-looking, kouros-type statue in the relief depicts a naked, wreathed Apollo, standing on a base, with a bow in his left hand and a deer in the right. To the left of the statue (see photo below) is a flaming, conical altar made of ashes. Either side of him is a young male figure, naked apart from a wreath and himation (cloak), holding a long torch. The torch bearers also stand on bases, but in contrast to the stiff, static pose of Apollo, they are shown in movement. |

|

|

| |

Detail of the statue of Apollo on the "Kanachos Relief" (above). |

| |

Kanachos of Sikyon (the Younger)

Κάναχος (Latin, Canachus)

Flourished around 400 BC (95th Olympiad, Pliny, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19).

From Sikyon, northwestern Peloponnese.

A pupil of Polykleitos of Argos (Pausanias, Book 6, chapter 13, section 7), and perhaps the grandson of Kanachos the Elder.

A statue of a boy boxer at Olympia: "Bycelus, the first Sicyonian to win the boys' boxing-match, had his statue made by Canachus of Sicyon, a pupil of the Argive Polycleitus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 13, section 7.

With Patrokles (Πατροκλές), Kanachos made statues of the Spartan commanders Epikydidas (Ἐπικυδίδας) and Eteonikos (Ἐτεόνικος), set up in Delphi to commemorate their victory over the Athenians at the naval Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC, at the end of the Peloponnesian War (Pausanias, Book 10, chapter 9, section 10). |

|

|

| |

Kephisodotos the Elder

Κηφισόδοτος

(Kephisodotos I or Cephisodotus the Elder)

Flourished around 400-360 BC

Athens

Placed by Pliny the Elder at the time of the 102nd Olympiad (372 BC) with Polykles, Leochares and Hypatodorus (Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19).

Perhaps the father or uncle of Praxiteles, and grandfather of Kephisodotos the Younger and Timarchos.

Pliny the Elder distinguished between two sculptors named Kephisodotos, attributing to Kephisodotos the Elder a bronze statue of Hermes holding the infant Dionysus:

"There were two artists of the name of Cephisodotus: the earlier of them made a figure of Mercury [Hermes] nursing Father Liber [Dionysus] when an infant; also of a man haranguing, with the hand elevated, the original of which is now unknown. The younger Cephisodotus executed statues of philosophers."

Pliny, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19.

Since Praxiteles is also said to have made a statue of Hermes holding the infant Dionysus (Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 17, section 3; see the Hermes page), it has been suggested that ancient authors may have confused the authorship of a single statue. However, around this time the theme of a deity carrying another god as an infant (e.g. Hermes with the infant Arkas, as well as the Tyche with the infant Ploutos and Eirene with Ploutos below) seems to have become popular as subject matter for artists.

A Herm of Hermes, the base of a statue of Hermes carrying the infant Dionysus, in the Museum of the Ancient Agora, Athens, Inv. No. S 33, is thought to be a Roman period copy of the statue group by Kephisodotos the Elder. |

|

|

| |

It is not known whether Pliny was referring to the Elder or Younger Kephisodotos in his mention of bronze statues of Athena and Zeus at Piraeus.

"Cephisodotus is the artist of an admirable Minerva [Athena], now erected in the port of Athens; as also of the altar before the Temple of Jupiter Servator [Zeus the Saviour], at the same place, to which, indeed, few works are comparable."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19.

The bronze Classicistic "Piraeus Athena" statue has been attributed to either Kephisodotos or Euphranor. Piraeus Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 4646.

Equally uncertain is Pausanias' reference to a statue group of Pentelic marble (i.e. marble from Athens) by Athenian sculptors Kephisodotos and Xenophon in the sanctuary of Zeus the Saviour (Διός Σωτῆρος, Dios Soteiros), in the agora of Megalopolis, Arcadia. The city was founded about 370 BC (see Demeter and Persephone part 2), so the statues must have been made at some time after. Archaeologists have not been able to date the scant remains of the sanctuary. Some remains identified as being of a slightly later date, suggesting that the sculptures may have been made during the generation of Kephisodotos the Younger, are considered to have been repairs or additions to the buildings.

"Here then is the Chamber, but the portico called 'Aristander's' in the market-place was built, they say, by Aristander, one of their townsfolk. Quite near to this portico, on the east, is a sanctuary of Zeus, surnamed Saviour. It is adorned with pillars round it. Zeus is seated on a throne, and by his side stand Megalopolis on the right and an image of Artemis Saviour on the left. These are of Pentelic marble and were made by the Athenians Cephisodotus and Xenophon."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 30, section 10.

Pausanias mentioned a sculptor named "Xenophon the Athenian" when discussing a statue in Thebes (see below).

The "Artemide di Kephisodotos", found in 1873 in the Horti Vettiani, Rome, is perhaps a Roman period copy of the statue of Artemis by Kephisodotos. Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline Musemus, Rome. Inv. No. MC 1123.

Pausanias noted a statue of the goddess Eirene (Εἰρήνη, Peace) holding the infant Ploutos (Πλοῦτον, Wealth) standing in the Athens Agora, but did not name the sculptor.

"After the statues of the eponymoi come statues of gods, Amphiaraus, and Eirene carrying the boy Plutus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 8, section 2.

Later he referred to a statue of the same subject in Athens, which he said was made by Kephisodotos. Here he also mentioned a statue representing a similar subject, Tyche (Τύχη; Latin, Fortuna) holding the infant Ploutos, in the sanctuary of Tyche at Thebes, partly made by Xenophon the Athenian. He may have been the Xenophon who worked with Kephisodotos at Megalopolis. Pausanias was delighted by the sculptors' respective concepts of the personification of Fortune or Peace as the mother or nurse of Wealth.

"After the sanctuary of Ammon at Thebes comes what is called the bird-observatory of Teiresias, and near it is a sanctuary of Fortune, who carries the child Wealth.

According to the Thebans, the hands and face of the image were made by Xenophon the Athenian, the rest of it by Callistonicus [Καλλιστόνικος], a native. It was a clever idea of these artists to place Wealth in the arms of Fortune, and so to suggest that she is his mother or nurse. Equally clever was the conception of Cephisodotus, who made the image of Peace for the Athenians with Wealth."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 16, section 2.

It is thought that the statue of Eirene with Ploutos was set up after the peace agreement between Athens and Sparta in 375/374 BC, from which time annual sacrifices to Eirene were intitiated. The image was depicted on Athenian coins and Panathenaic prize amphorae.

For the Athenian coins, see: Friedrich Imhoof-Blumer and Percy Gardner, A numismatic commentary on Pausanias, page 147 and plate DD, ix and x. Reprinted from The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 1885, 1886, 1887. Richard Clay and Sons, London and Bungay, 1887. At the Internet Archive.

Eirene was evidently recognized as a deity in Athens long before this time. In Aristophanes' comedy Eirene (Εἰρήνη, Peace), written in 421 BC, during the Peloponnesian War, the goddess has been buried in a deep pit by the war god Ares, and Zeus has forbidden her exhumation. Nevertheless, the Athenian farmer Trygaeus persuades people from all over Greece to dig her up. She is angry with them for having rejected peace so often and refuses to speak, communicating only through Hermes. The figure of Eirene in the play has been interpreted as being a statue. At the end of the play Trygaeus prays to Peace as a familiar deity who presides over marriages and enables trade, which brings prosperity:

"Oh! Peace, mighty queen, venerated goddess, thou, who presidest over choruses and at nuptials, deign to accept the sacrifices we offer thee.

... Make excellent commodities flow to our markets, fine heads of garlic, early cucumbers, apples, pomegranates and nice little cloaks for the slaves; make them bring geese, ducks, pigeons and larks from Boeotia and baskets of eels from Lake Copais; we shall all rush to buy them..."'

The so-called "Leucothea group", a Roman period statue group found on Delos and now in Munich, is thought to be a copy of Kephisodotos' Eirene and Ploutos. Glyptothek, Munich. Inv. No. 219 (see photo, above right). There are also fragments in various collections, including a part of the Ploutos figure in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Studies of the Munich statue have led scholars to believe that the original was made of bronze, and that Eirene originally held a sceptre in her raised right hand.

After describing Thebes, Pausanias took his readers through Boeotia to the Grove of the Muses on Mount Helikon. He wrote that there were two groups of statues depicting the Muses, the first in which all nine were made by Kephisodotos, and the second in which Kephisodotos, Strongylion and Olympiosthenes (Ὀλυμπιοσθένης) had each made three.

"The first images of the Muses are of them all, from the hand of Cephisodotus, while a little farther on are three, also from the hand of Cephisodotus, and three more by Strongylion, an excellent artist of oxen and horses. The remaining three were made by Olympiosthenes."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 30, section 1. |

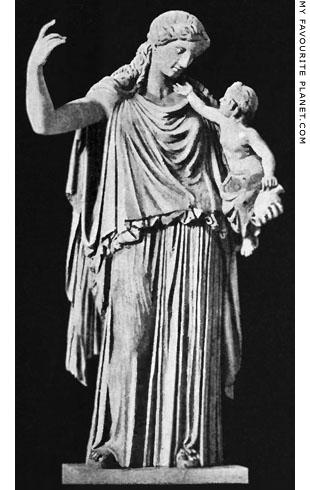

A Roman period marble statue of Eirene

holding the infant Ploutos, thought to be

a copy of the statue made by Kephisodotos

the Elder around 370 BC that stood in the

Athens Agora. Height 201 cm.

Glyptothek, Munich. Inv. No. 219.

Image source:

Ernest Arthur Gardner, A Handbook of

Greek Sculptures Part 2, Fig. 81, page 353.

Macmillan and Co., London, 1897. |

| |

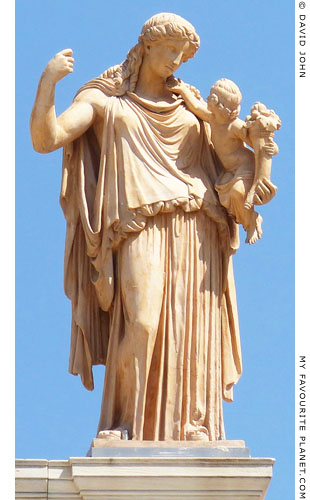

A modern copy of the statue of Eirene

holding the infant Ploutos on the roof

above the entrance to the National

Archaeological Museum, Athens. |

| |

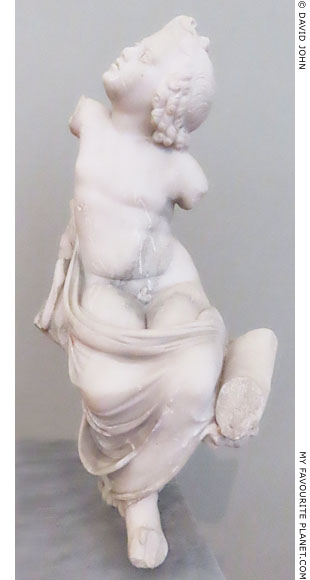

A marble statuette of Ploutos, part of a

Roman period copy of the statue of Eirene

holding the infant Ploutos by Kephisodotos

the Elder. Plouto is supported on the left

arm of Eirene, a part of whose hand can

be seen, to the right of the child's left

knee, holding part of the cornucopia.

1st century AD. Found in the

harbour of Piraeus, Greece.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 175. |

| |

| |

Kephisodotos the Younger

Κηφισόδοτος ο Νεότερος

(Kephisodotos II or Cephisodotus the Younger)

Athens, late 4th - early 3rd century BC (around 345-290 BC)

Pliny the Elder placed him at the time of the 121st Olympiad (296 BC) with Eutychides, Euthycrates, Laippus, Timarchus (probably Timarchos), and Pyromachus (Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19).

He was the grandson of Kephisodotos the Elder, son of Praxiteles (Pliny, Book 36, chapter 4) and brother of Timarchos.

Kephisodotos the Younger was mentioned by Pliny the Elder among Greek sculptors in bronze:

"The younger Cephisodotus executed statues of philosophers."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pliny did not tell us which philosophers he portrayed, but listed other works by him when discussing makers of marble sculpture, including a statue group at Pergamon and others which had later been taken to Rome.

"Cephisodotus, the son of Praxiteles, inherited his father's talent. There is, by him, at Pergamus, a splendid Group of Wrestlers [symplegma], a work that has been highly praised, and in which the fingers have all the appearance of being impressed upon real flesh rather than upon marble. At Rome there are by him, a Latona [Leto], in the Temple of the Palatium; a Venus [Aphrodite], in the buildings that are memorials of Asinius Pollio [75 BC - 4 AD]; and an Aesculapius [Asklepios], and a Diana [Artemis], in the Temple of Juno situated within the Porticos of Octavia."

Pliny, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4.

Pliny's "symplegma" has been translated in other editions simply as "persons grappling", which is a little vague. Modern scholars often refer to depictions of grappling or wrestling figures as symplegmata (from σύμπλεγμα, symplegma, braided, or entwined; plural symplegmata). See, for example, a statue group of Hermaphroditus and a satyr.

It has been suggested that the "Uffizi Wrestlers" (or "Pancrastinae"), a Roman period marble statue group found in Rome in 1583 and now in the Uffizi, Florence, Inv. No. ASN 216, may be a copy of the bronze wrestlers by Kephisodotos the Younger mentioned by Pliny. Nowever, this is just one of several theories concerning the history of the sculpture and the associated "Uffizi Niobid Group" statues.

Pausanias mentioned that a statue of Enyo (Ἐνυο, Warlike) in the sanctuary of Ares in the Athens Agora was made by "the sons of Praxiteles", but he does not name them or say how many they were. He is believed to have been referring to Kephisodotos the Younger and Timarchos (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 8, section 4).

Pausanias also wrote that the sons of Praxiteles built an altar that stood next to a bronze statue of Dionysus in the agora on the acropolis of Thebes, Boeotia.

"There is also a story that along with the thunderbolt hurled at the bridal chamber of Semele there fell a log from heaven. They say that Polydorus adorned this log with bronze and called it Dionysus Cadmus. Near is an image of Dionysus; Onasimedes made it of solid bronze. The altar was built by the sons of Praxiteles."

Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 12, section 4.

A statue of Menander (Athenian comic playwright, circa 342-290 BC) at the Theatre of Dionysos, Athens, was mentioned by Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 21, section 1), although he did not say who made it. A pedestal, dated 291/290 BC, discovered at the theatre in 1862, bears an inscription with the name "Menandros", below which are the signatures of Kephisodotos and Timarchos.

Μένανδρος

Κηφισόδοτος Τίμαρχος ἐπόησαν

Menandros

Kephisodotos and Timarchos made it

Inscription IG II² 3775.

This is thought have been the base of the bronze statue seen by Pausanias. From this and other epigraphical evidence it is also believed that the two sculptors were brothers and the sons of Praxiteles. The pedestal is displayed at the theatre, with a modern composite cast reconstruction of the statue of the seated playwright, made from fragments of Roman period copies (in Naples and Venice). 71 Roman copies of the statue's head have survived, more than of any other ancient poet's portrait, as well as nine replicas of the body.

After describing Thebes, Pausanias took his readers through Boeotia to the Grove of the Muses on Mount Helikon (see below). He wrote that there were two groups of statues depicting the Muses, the first in which all nine were made by Kephisodotos, and the second in which Kephisodotos, Strongylion and Olympiosthenes (Ὀλυμπιοσθένης) had each made three.

"The first images of the Muses are of them all, from the hand of Cephisodotus, while a little farther on are three, also from the hand of Cephisodotus, and three more by Strongylion, an excellent artist of oxen and horses. The remaining three were made by Olympiosthenes."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 30, section 1. |

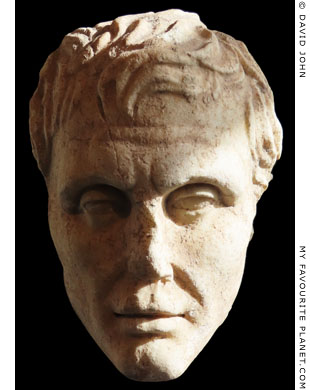

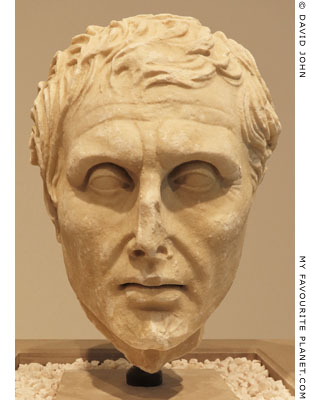

Marble portrait head of Menander.

2nd century BC, Roman Imperial period.

Pentelic marble. Although only the face

and front of the head have survived, this

is one of the best preserved examples

of the type believed to be copies of the

bronze statue made by Kephisodotos

and Timarchos for the Theatre of Dionysos,

Athens, soon after 291 BC.

Antikenhalle (Hall of Antiquities),

Semperbau, Dresden. Inv. No. Hm 198.

Donated by Franz Studniczka, Leipzig, 1899. |

| |

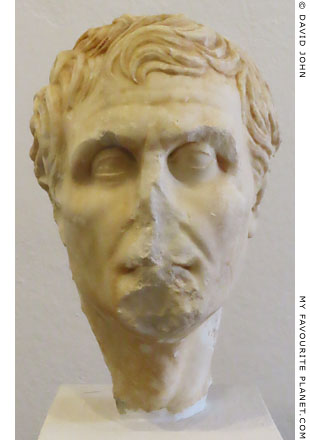

Marble portrait head of Menander

from Corfu.

Roman Imperial period, first half of

the 2nd century AD. Height 29.5 cm.

Corfu Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 133.

See the statue of Menander and the

inscribed pedestal at the theatre

on Athens Acropolis page 36. |

| |

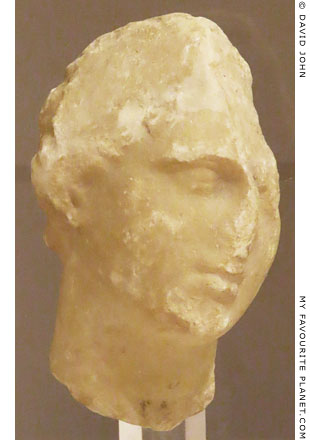

Marble portrait head of Menander

from Rhodes.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

In a dialogue written by the early Hellenistic poet Herondas, two characters, Kynno and Kokkale, discuss altars and statues of Asklepios, "Lord Paieon, ruler of Trikka", his parents (Koronis and Apollo) and children. Kynno says that according to the inscription on the base, they were made by "the sons of Praxiteles". It is thought that the scene may have been set in the Asklepieion on the island of Kos.

"Kynno: Hail, Lord Paieon, ruler of Trikka, who dwells in sweet Kos and Epidauros too; hail Koronis too, who bore you, and Apollo, and Hygieia whom you touch with your right hand, and those whose honoured altars are here too; hail to Panake, Epio, Ieso, and those who sacked house and walls of Leomedon, doctors of savage diseases, Podaleirios and Machaon, and all the gods and goddesses who inhabit your shrine, father Paieon. Come gracefully to accept this cock . . .

Kokkale: O Kynno dear, what fair statues! What craftsman, pray, made this stone, and who set it up?

Kynno: The sons of Praxiteles: don't you see the letters on the base? And Euthies son of Prexon set it up.

Kokkale: May Paieon be gracious with them and to Euthies for their fair works. [They then turn to admire other dedications before entering the temple with their offering]."

Herondas, Mimiambos, 4.

According to the Syrian theologian Tatian (Τατιανός, circa 120-180 AD), Kephisodotos made bronze statues of poetesses, one of Myro of Byzantium, and with Euthykrates one of Anyte of Tegea. He said they were among works by renowned Greek sculptors which had been taken to Rome (see the quote under Menestratos). Since Myro (Μυρώ; or Moero, Μοιρώ) probably lived in the late 4th to early 3rd century BC, it is thought more likely that her statue was made by the younger rather than the elder Kephisodotos.

Several statue bases signed by Kephisodotos the Younger have been discovered, including an early 3rd century BC dedication to Athena by Philoumene, daughter of Leosthenes, found at the Athens Acropolis. Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. Acr. Y 3627. A few, including the base of the Menander statue, are also signed by Timarchos. There is only one known signature of Timarchos alone, found at Rome in 1874.

Some scholars believe that around 290 BC Kephisodotos and Timarchos made a marble statue of Aphrodite known by copies of the Capitoline Aphrodite type, named after the best example. Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 409. 2nd century AD. Height 193 cm. It was found near the church of San Vitale, between the Quirinal and Viminal, Rome. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

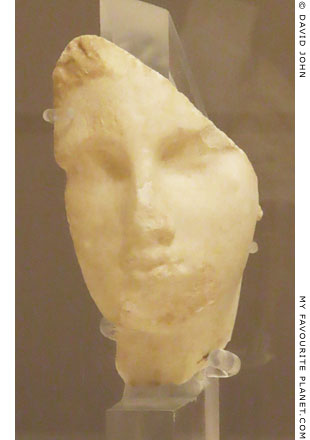

Two fragmentary marble smaller than lifesize statue heads of females, found in the

Asklepieion of Kos. 340-330 BC. Attributed to the workshop of Praxiteles' sons.

Kos Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

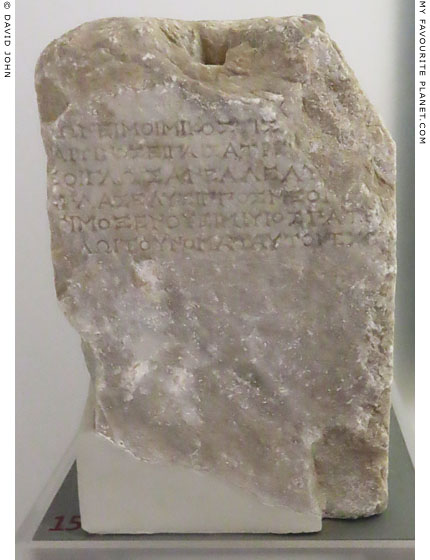

Nine inscribed marble blocks from the base for bronze statues of the nine Helikonian Muses,

from the sanctuary of the Muses on Mount Helikon, near Thespiai, Boeotia, central Greece.

1st century BC, during the reign of Augustus.

Courtyard of Thebes Archaeological Museum.

|

The sanctuary of the Muses, the patron goddesses of the arts and sciences, in the Grove of the Muses, near Thespiai, was one of the most important centres for their cult. It flourished particularly during the Hellenistic and early Roman Imperial periods. Among the many statues of the Muses set up there were the bronzes which stood on this base, dedicated by the Thespians. Inscribed below the figure of each Muse was her name and a short epigram in her honour by the Corinthian poet Onestos.

Pliny the Elder (Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4) wrote that the artist and art historian Pasiteles "speaks in terms of high admiration" of a statue group of the Thespian Muses, the "Thespiades", taken from Thespiae to Rome by consul Lucius Mummius Achaicus (the conquerer of Achaia who destroyed Corinth in 146 BC) and set up near the Temple of Felicity. Unfortunately Pliny did not describe the statue group or tell us who made it. In the same chapter Pliny attributed another group of "Thespiades" in the buildings of Asinius Pollio in Rome to Cleomenes, but did not specify which of the artists of this name was meant. See Pasiteles for further details. |

|

|

| |

Klearchos of Rhegion

Κλέαρχος (Clearchus of Rhegium)

Early 5th century BC

Rhegion (Ῥήγιον; Latin, Rhegium), southwest Italy

He was a pupil of Eucheiros (Εὔχειρος) of Corinth and the teacher Pythagoras of Rhegion, who was a contemporary of Myron and Polykleitos the Elder.

The only known work by Klearchos was a statue of Zeus Most High (Διὸς Ὑπάτος, Dios Ypatos) at Sparta mentioned by Pausanias, made from hammered bronze plates riveted together. Pausanias related that it was the most ancient bronze statue and that Klearchos was said to have been been a pupil of Dipoenos and Skyllis (6th century BC) or Daidalos, either the mythical Daidalos or Daidalos of Sikyon (5th - 4th century BC).

"On the right of the Lady of the Bronze House has been set up an image of Zeus Most High, the oldest image that is made of bronze. It is not wrought in one piece. Each of the limbs has been hammered separately; these are fitted together, being prevented from coming apart by nails. They say that the artist was Clearchus of Rhegium, who is said by some to have been a pupil of Dipoenus and Scyllis, by others of Daedalus himself."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 3, chapter 17, section 6.

Later, when discussing a statue at Olympia by Pythagoras of Rhegion, Pausanias provided a very different account of Klearchos:

"The statue was made by Pythagoras of Rhegium, an excellent sculptor if ever there was one. They say that he studied under Clearchus, who was likewise a native of Rhegium, and a pupil of Eucheirus. Eucheirus, it is said, was a Corinthian, and attended the school of Syadras and Chartas, men of Sparta."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 4, section 4. |

|

|

| |

Kresilas

Κρησίλας; Latin, Cresilas; also referred to as Ctesilas or Ctesilaüs

From Kydonia (Κυδωνία, today Chania), on the north coast of Crete.

Circa 480-410 BC

He is thought to have been a student of Dorotheos of Argos (Δωρόθεος), and may have worked with him at Delphi and Hermione. This theory is mainly based on the discovery of signatures of the two artists on the bases of related statues at both places (see Kresilas signatures on the Kresilas page).

From literary and epigraphical evidence, he appears to have worked between around 450 and 410 BC mainly in Athens, probably as a follower of the school of Myron, known for its idealistic portraiture. |

|

For further information see the Kresilas page. |

|

|

| |

Kritios

Κριτίος or Κριτίας (Latin, Critius or Critias)

Working in Athens, early-mid 5th century BC

Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19)

placed "Critias" in the 83rd Olympiad (448-445 BC), about the year of our City 300 (years since the legendary foundation of Rome in 753 BC), along with Pheidias, Alcamenes, Nesiotes (or perhaps "Nestocles") and Hegias. As pupils of Critias, later in the same chapter Pliny named Diodorus and Scymnus, among celebrated artists "who had not produced any first-rate works".

He was probably a pupil of Antenor, and was a teacher of Ptolichus of Korkyra (Πτόλιχος ὁ Κορκυραῖος; Korkyra is today known in English as Corfu). Pausanias discussed the school of "Attic Kritias" while describing statues of athletes in the Sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia:

"The statue of Hippus of Elis, who won the boys' boxing-match, was made by Damocritus of Sicyon [Δαμόκριτος Σικυώνιος], of the school of Attic Critias [τὸν Ἀττικὸν Κριτίαν], being removed from him by four generations of teachers. For Critias himself taught Ptolichus of Corcyra, Amphion [Ἀμφίων] was the pupil of Ptolichus, and taught Pison of Calaureia [Πίσων Καλαυρείας], who was the teacher of Damocritus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 3, section 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

Kritios and Nesiotes made the statue pair of the "Tyrannicides" (Τυραννοκτόνοι) Harmodius and Aristogeiton (Ἁρμόδιος καὶ Ἀριστογείτων), who in 514 BC assassinated Hipparchos, one of the sons and successors of the Athenian tyrant Peisistratos, and were then themselves killed. The statues were set up in the Athenian Agora in 477 BC to replace those made Antenor, which had been taken as booty by Xerxes I of Persia in 480 BC. Pausanias summarized the tale of the statues, but did not mention Nesiotes:

"Hard by stand statues of Harmodius and Aristogiton, who killed Hipparchus. The reason of this act and the method of its execution have been related by others; of the figures some were made by Critius, the old ones being the work of Antenor. When Xerxes took Athens after the Athenians had abandoned the city he took away these statues also among the spoils, but they were afterwards restored to the Athenians by Antiochus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 8, section 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

The Roman period copy of the statue group, now in Naples, may have been made from plaster casts of the originals in a copyist's workshop in Baiae in the Bay of Naples, where in 1952 part of a cast of the head of Aristogeiton (Baiae Museum. Inv. No. 174.479) was discovered.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. G 103 and G 104.

Pausanias also noted a statue of the athlete Epicharinos (Ἐπιχαρίνος) by Kritios (Κριτίας) near a bronze statue of the Wooden Horse of Troy on the Athens Acropolis.

"Of the statues that stand after the horse, the likeness of Epicharinus who practised the race in armour was made by Critius..."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 23, section 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

Lucian of Samosata referred to the stiff Archaic style of Hegesias (see Hegias of Athens), Kritios and Nesiotes:

"... the clean-cut, sinewy, hard, firmly outlined productions of Hegesias, or the school of Critius and Nesiotes."

Lucian, The rhetorician’s vade mecum (written around 178 AD).

The smaller than lifesize marble statue of a nude youth known as "the Kritian Boy" (or "Kritios Boy"), found on the Athens Acropolis in 1865 (the head in 1888), has been named due to similarities of the head to that of the statue of Harmodius (the younger of the tyrannicides). Dated around 480 BC, it is considered to be the earliest explicit example of Classical sculpture and a radical departure from Archaic kouros statue types (see, for example the colossal "Isches Kouros", "the Ram-Carrier of Thasos" and "the Strangford Apollo", on Samos gallery page 4).

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. Acr. 698.

Height 116.7 cm.

A new article about Kritios and Nesiotes is currently in preparation. |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors |

L |

|

|

|

| |

| |

Leochares

Λεοχάρης (Lion’s Grace)

4th century BC, working around 370-320 BC

Athens

According to Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19), Leochares was working in bronze in the 102nd Olympiad (370 BC), as a contemporary of Kephisodotos the Elder, Polykles and Hypatodorus. However, many scholars believe this date is far too early for the height of his career, particularly taking into consideration the projects he is said to have worked on and the other artists he worked with.

Leochares made chryselephantine (ivory and gold) statues for the Philippeion at Olympia (see Alexander the Great), commissioned by Philip II of Macedonia following his victory at the Battle of Chaeroneia in 338 BC, and probably completed during the reign of his son Alexander the Great. Pausanias mentioned statues there of Philip, Alexander, Olympias (Alexander's mother), Amyntas III and Eurydice I (Philip's parents).

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 20, sections 9-10.

See: Katherine Denkers, The Philippeion at Olympia: The true image of Philip? MA thesis, McMaster University, 2012.

Marble head of Alexander the Great, 340-330 BC. Thought to be an original work of Leochares. Found in 1886 near the Erechtheion of the Athens Acropolis. It has been suggested that the portrait of Alexander in the Philippeion at Olympia (see Alexander the Great) may have been a copy of this sculpture. Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. Acr. 1331.

Plutarch wrote that Leochares and Lysippos made a bronze statue group depicting Alexander and his general Krateros hunting a lion, which was dedicated by Krateros at Delphi. Pliny the Elder also mentioned a bronze statue of Alexander hunting by Lysippos, "now consecrated at Delphi", but did not mention that Leochares worked on the sculpture. This is thought to have been one of Leochares' last works and to have been made around 320 BC. The site of the monument known as the "Offering of Krateros" or the "Ex-voto of Krateros" has been discovered in Delphi, along with the inscribed dedication by the son of Krateros (see Alexander the Great).

Plutarch, Life of Alexander, chapter 40, section 5; Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19.

Leochares made a statue of Apollo (probably around 338-322 BC) which stood next to one by Kalamis in front of the Temple of Apollo Patroos (Paternal) in the Athenian Agora (Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 3, section 4; see Euphranor). He made a statue of Zeus which stood on the Athens Acropolis, and which Pausanias included in a list of Athenian monuments he recommended to "those who prefer artistic workmanship to mere antiquity" (Pausanias, Book 1, chapter 24, sections 3-4). He also made statues of Zeus and the People (Δῆμος, Demos) which stood in the sanctuary of Athena and Zeus at Piraeus (Pausanias, Book 1, chapter 1, section 3).

Around 350 BC he made sculptures for the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus in Caria, western Anatolia (today Bodrum, Turkey), with Bryaxis, Skopas, and perhaps Timotheos and Praxiteles. According to Pliny the Elder, he worked on the west side of the monument. (Vitruvius, Ten books on architecture, Book 7, Introduction, section 13; Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4; see Bryaxis)

According to Vitruvius, either Leochares or Timotheos made a colossal acrolithic statue of Ares for the temple of Ares in Halicarnassus:

"At the top of the hill, in the centre, is the fane of Mars, containing a colossal acrolithic statue by the famous hand of Leochares. That is, some think that this statue is by Leochares, others by Timotheus."

Vitruvius, Ten books on architecture, Book 2, chapter 8, section 11.

Other bronze sculptures by Leochares mentioned by Pliny:

"Leochares made a bronze representing the eagle carrying off Ganymede: the eagle has all the appearance of being sensible of the importance of his burden, and for whom he is carrying it [Zeus], being careful not to injure the youth with his talons, even through the garments. He executed a figure, also, of Autolycus, who had been victorious in the contests of the Pancratium, and for whom Xenophon wrote his Symposium; the figure, also, of Jupiter Tonans in the Capitol, the most admired of all his works; and a statue of Apollo crowned with a diadem. He executed, also, a figure of Lyciscus, and one of the boy Lagon, full of the archness and low-bred cunning of the slave."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19.

The figure of Autolycus (Αὐτόλυκος), a champion in the pankration (παγκράτιον, a no-holds-barred mixture of boxing and wrestling), perhaps in the Panathenaic games of 422 BC, may have been the statue reported by Pausanias as standing in the Prytaneion (Πρυτανεῖον, town hall), below the eastern end of the Athens Acropolis. Some scholars believe that Pliny's text is confused, and that the statue may have been made by Lykios (see Lykios below).

"Hard by is the Prytaneum, in which the laws of Solon are inscribed, and figures are placed of the goddesses Peace [Εἰρήνη, Eirine] and Hestia [Ἑστία], while among the statues is Autolycus the pancratiast."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 18, section 3.

The statue of Jupiter Tonans (Ζεὺς βρονταῖος, Zeus Brontaios, Thundering Zeus), made of Delian bronze (Natural history, Book 34, chapter 5), is thought to have been an early work of Leochares which stood in Megalopolis, Arcadia (founded about 370 BC, see Demeter and Persephone part 2). It was later taken to Rome and set up by Augustus in the Temple of Jupiter Tonans he built on the Capitol of highly polished solid blocks of marble (Natural history, Book 36, chapter 8).

Leochares' signature has been found on 10 statue bases in Athens, many fragmentary and incomplete. They include:

A dedication to Asklepios, around 338 BC. Inscription IG II² 2831+4367 (also IG II² 2831, IG II² 4367 and SEG 30:163).

A dedication by officials, mid 4th century BC. Inscription IG II³ 463. Epigraphical Museum, Athens, Inv. No. EM 10601).

The dedication of Pandaites and Pasikles, a base for a group of five statues of Pasikles of Potamos and his family, around 330 BC. Two statues are signed by Sthennis and two by Leochares. The signature for the fifth statue is missing. Inscription IG II² 3829.

For seven of the signatures of Leochares, see: Emanuel Loewy (1857-1938), Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer, Nos. 77-83, pages 60-65. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Lykios

Λύκιος (Latin, Lycius)

Mid 5th century BC

From Eleutherai (Ἐλευθεραί), near the border between northern Attica and Boeotia. He worked at Athens and Olympia.

Son and/or pupil of Myron of Eleutherai (son, according to Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 23, section 7, and Book 5, chapter 22, section 3; pupil, according to Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19).

For more about Eleutherai and Athens, see Athens Acropolis gallery page 36.

Statues by Lykios in Athens and Olympia are known from literary and epigraphical evidence. He appears to have continued the work of his father and/or teacher Myron. Like other contemporary sculptors working in Athens, he was probably involved in the Periclean building project on the Acropolis, although there appears to be no evidence for modern claims that he worked there as an architect.

Pausanias saw a statue of a boy holding a perirrhanterion (περιρραντήριον, a vessel or sprinkler for holy water) by Lykios, next to Myron's statue of Perseus on the Athens Acropolis, perhaps just inside the Propylaia, near the sanctuary of Athena Hygieia, in front of the sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia.

"I remember looking at other things also on the Athenian Acropolis, a bronze boy holding the sprinkler, by Lycius son of Myron, and Myron's Perseus after beheading Medusa."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 23, section 7. At Perseus Digital Library.

He also described an extensive group of statues near the Hippodamion (Ἱπποδάμιον) in Olympia, made by Lykios for Apollonia (Ἀπολλωνία πρὸς Ἐπίδαμνον, Apollonia pros Epidamnon; in Illyria or Epirus; today near Pojani, Albania) on the Ionian Sea, a colony of Korkyra (Corfu). The statues depicted scenes from the Epic Cycle of poems dealing with the Trojan War (see Homer). In one scene Thetis (mother of Achilles) and Hemera (Eos, mother of Memnon) made pleas to Zeus for the lives of their respective sons. The other sculptures included five pairs of Homeric heroes in duels:

"By the side of what is called the Hippodamium is a semicircular stone pedestal, and on it are Zeus, Thetis, and Day [Hemera] entreating Zeus on behalf of her children. These are on the middle of the pedestal. There are Achilles and Memnon, one at either edge of the pedestal, representing a pair of combatants in position. There are other pairs similarly opposed, foreigner against Greek: Odysseus opposed to Helenus, reputed to be the cleverest men in the respective armies; Alexander [Paris] and Menelaus, in virtue of their ancient feud; Aeneas and Diomedes, and Deiphobus and Ajax son of Telamon.

These are the work of Lycius, the son of Myron, and were dedicated by the people of Apollonia on the Ionian sea."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 22, sections 2-3. At Perseus Digital Library.

Two fragments of black limestone found at Olympia, inscribed at the edges at which they join with the name Memnon (Μέμνων), are thought to be parts of the semicircular pedestal on which Lykios' statue group stood.

Μέμνω - ν

Inscription IvO 692 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Height 30.5 - 31.5 cm, combined width 54 cm, depth 88 cm.

See: Ernst Curtius and Friedrich Adler (editors), Olympia: die Ergebnisse der von dem Deutschen Reich veranstalteten Ausgrabung, Wilhelm Dittenberger and Karl Purgold, Textband 5: Die Inschriften von Olympia, No. 692, columns 711-712. A. Ascher & Co., Berlin, 1896. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Athenaeus of Naucratis (2nd - 3rd century AD), citing Polemo (probably the geographer Polemo Periegetes, also cited by Strabo), referred to Lykios as a Boeotian from Eleutherai and a son of Myron. He refuted a claim by the grammarian Didymos that he made vessels known as φίαλας λυκουργεῖς (Lykian or Lycian phiales) or λυκιουργεῖς (Lykiourgeis, Lycian cups or Lycian ware) mentioned in a speech by Demosthenes.

"There is also the Lyciurges. The things which are so called are some kinds of phialae, which derive their name from Lycon who made them, just as the Cononii are the cups made by Conon. Now, Demosthenes, in his Oration for the Crown, mentions Lycon; and he does so again, in his oration against Timotheus for an assault, where he says, 'two lyciurgeis Phialae'. And in his speech against Timotheus he also says, 'He gives Phormion, with the money, also two lyciurgeis Phialae to put away'. And Didymus the grammarian says that these are cups made by Lycius. And this Lycius was a Boeotian by birth, of the town of Eleutherae, a son of Myron the sculptor, as Polemo relates in the first book of his treatise on the Acropolis of Athens; but the grammarian is ignorant that one could never find such a formation of a word as that derived from proper names, but only from cities or nations."

Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists, Book 11, chapter 72. At Perseus Digital Library.

The same information appears in the Suda, where it is argued that such vessels were named after Lycia in southwest Anatolia:

"Λυκιουργίς: Lykian-ware, Lycian-ware: Demosthenes in the [speech] Against Timotheos uses the expression. Didymos asserts that the bowls manufactured by Lykios the son of Myron were referred to in this way. But the grammarian seems to be unaware that one would not find such an expression arising from proper names, rather from cities and peoples; like 'a couch Milesian-made' and the like. So perhaps one should write, in Herodotus [book] seven, not two hunting-spears 'wolf-made' but 'Lykian-made', in order that, just as in Demosthenes, they may be described as being of Lykian manufacture."

Suda, § la.807. At ToposText.

This rather involved pedantic argument has led modern scholars to ask whether Lykios did make such vessels, perhaps chased silver phiales (libation bowls), as other sculptors are said have done, including Myron and Kalamis.

Pliny the Elder named Lykios as a pupil of Myron in a list of sculptors in bronze. A little later in the same chapter he mentioned a statue of a boy and a statue group of the Argonauts. After continuing with works by Leochares, he adds another statue of a boy by Lykios. Some scholars have considered this confusing text may actually have meant that Lykios also made one or more of the statues ascribed to Leochares, particularly the statue of Autolycus.

"Lycius, too, was the pupil of Myron."

"Lycius was the pupil of Myron: he made a figure representing a boy blowing a nearly extinguished fire, well worthy of his master, as also figures of the Argonauts. Leochares made a bronze representing the eagle carrying off Ganymede: the eagle has all the appearance of being sensible of the importance of his burden, and for whom he is carrying it, being careful not to injure the youth with his talons, even through the garments. He executed a figure, also, of Autolycus, who had been victorious in the contests of the Pancratium, and for whom Xenophon wrote his Symposium; the figure, also, of Jupiter Tonans in the Capitol, the most admired of all his works; and a statue of Apollo crowned with a diadem. He executed, also, a figure of Lyciscus, and one of the boy Lagon, full of the archness and low-bred cunning of the slave. Lycius also made a figure of a boy burning perfumes."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19.

An inscribed grey marble statue base (perhaps Pentelic or Hymettian marble) signed by Lykios, son of Myron, and dated around 450-430 BC, was found in 1889 near southwest corner of the Parthenon, on the Athens Acropolis. Dowel holes in the top of the base (see drawing below) indicate that the statue was of a horse (with or without a rider), facing right, being led by a man standing next to it. The monument was dedicated by three cavalry generals (hipparchs) to commemorate a battle, although its place and date remain a subject of debate.

ℎοι ℎι[ππ]ῆς [⋮] ἀπὸ τ̣ο͂ν [πο]λεμίον ⋮ ℎιππαρ[χ]ό[ν]-

τον ⋮ Λακεδ̣αιμονίο [⋮] Ξ̣[ε]νοφο͂ντος ⋮ Προν[ά]π[ο]-

ς ⋮ Λύκιο[ς ⋮ ἐ]ποίησεν [⋮] Ἐλευθερεὺς [⋮ Μ]ύ̣[ρ]ο̣ν̣[ος].

The cavalry [dedicated this] from [the spoils of] the enemy. The cavalry commanders

were Lakedaimonios, Xenophon, Pronapes.

Lykios of Eleutherai, son of Myron, made it.

Inscription IG I³ 511 (= IG I² 400,Ia; Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 135) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

In the early Roman Imperial period, probably in the 1st century BC during the reign of Augustus, the base was turned on its head and reinscribed on the opposite side with an exact copy of the original dedication in archaistic early Attic lettering. IG I² 400,Ib (DAA 135a). The statue placed on the reused based is thought to have been a newly-made work of a similar type, although probably not a copy of Lykios' group, since the dowel holes are distributed differently.

Around the same time another, apparently new base of grey Hymettian marble was also inscribed with a copy of the dedication in the same archaistic lettering, but by a different stonemason. Three fragments of the inscription were discovered at different times in various places around the Acropolis IG I² 400,II (DAA 135b). The findspots of two fragments are unknown, but "Fragment b" was found in 1880, built into a late wall to the west of the Pedestal of Agrippa.

Later, another block of the first pedestal (DAA 135a) was inscribed again, apparently presenting the statue as a dedication by the demos (the people) to Germanicus Caesar, the adopted son and heir of Emperor Tiberius (reigned 14-37 AD). This may have been made at the time of Germanicus' visit to Athens in 18 AD.

ὁ δῆμος

Γερ[μ]ανικ[ὸν Κα]ίσαρα

θεοῦ Σε[βαστοῦ ἔγγονον].

The demos [dedicated this statue of]

Germanicus Caesar,

descendant of the divine Augustus.

Inscription IG II² 3260 (see DAA 135, 135a, 135b) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

It is therefore believed that Lykios' original statues may have been destroyed or moved elsewhere (perhaps taken to Rome?), and later replaced by two equestrian statues on similar bases, perhaps standing on a single pedestal. Later one or both of the statues were rededicated to Germanicus Caesar. It is also thought that these may have been the statues Pausanias saw on his way up to the Propylaia of the Athens Acropolis, and that he may have been confused or bemused by the extra dedication to Germanicus. The two early Imperial statues may have depicted Gryllus and Diodorus, sons of the general Xenophon of Athens, or the Dioskouroi standing with horses.

"Now as to the statues of the horsemen, I cannot tell for certain whether they are the sons of Xenophon or whether they were made merely to beautify the place."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 22, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

The original inscription and the dedication to Germaninus have been placed on the bastion of the Athena Nike Temple. See a photo, drawings and further discussion on Athens Acropolis page 8.

See also:

Lilian Hamilton Jeffery, Lykios son of Myron: the epigraphic evidence. In: Στήλη Τόμος Εις Μνήμην Νικολάου Κοντολέοντος, pages 51-54. 1971.

Jerome Jordan Pollitt, The art of ancient Greece: sources and documents, Chapter 5, pages 69-71. Cambridge University Press, 1990. At Google Books.

A fragment of another statue base, made of limestone, with a now incomplete two-line inscription thought to include a dedication and Lykios' signature, was found in 1865, northeast of Propylaia. The forms of the lettering are similar to those on the cavalry monunent above (DAA 135). It is not certain whether both lines are part of the same inscription, and reconstruction has posed problems for scholars. It is is thought that Lykios may have dedicated the statue himself, perhaps around 440-430 BC. According to another interpretation, the first line may be a dedication by Semichides of Eleutherai (before 440 BC), and the second the signature of Lykios of Eleutherai, son of Myron.

[Ἀθεναίαι ἀπαρχὲν Σεμιχίδ]ες Ἐλευθερε[ὺς ἀνέθεκεν]

[Λύκιος ἐποίεσεν Ἐλευθερεὺς] Μύρονος. [vac.]

Inscription DAA 138 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6272.

Height 15 cm, length 26 cm, width 8 cm. The top of the slab is smooth, with no traces of cutting.

See also IG I³ 892 (also IG I² 537) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

It has been suggested that the statue which stood on this base may have been Lykios' bronze boy holding a perirrhanterion mentioned by Pausanias. |

|

|

| |

A drawing of the top of the base of the cavalry statue group by Lykios on the

Athens Acropolis (see above), showing the dowel holes for affixing the statues.

Source: Carlo Anti, Lykios, Fig. 9, page 40. In: Bullettino della Commissione

Archeologica Comunale di Roma, Anno 47 (1919), pages 55-138.

P. Maglione & C. Strini, Rome, 1921. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

Lysippos

Λύσιππος (Latin, Lysippus)

Circa 390-305 BC

Born at Sikyon, northeastern Peloponnese.

An autodidact, he was originally a metal smith, became a prolific sculptor, and later head of the school of Argos and Sikyon.

He was the official sculptor of Alexander the Great, and, according to Plutarch, the only artist permitted to portray him in statues. Plutarch also mentioned that he made a statue of Alexander holding a spear and compared it to the painting by Apelles of Alexander with a thunderbolt (Moralia, 335A-B, 335F and 360D).

Moralia, 335A-B

"Apelles the painter and Lysippus the sculptor also lived in the time of Alexander. The former painted 'Alexander wielding the Thunderbolt' so vividly and with so natural an expression, that men said that, of the two Alexanders, Alexander, son of Philip, was invincible, but the Alexander of Apelles was inimitable.

And when Lysippus modelled his first statue of Alexander which represented him looking up with his face turned towards the heavens (as indeed Alexander often did look, with a slight inclination of his head to one side), someone engraved these verses on the statue, not without some plausibility.

Eager to speak seems the statue of bronze, up to Zeus as it gazes:

'Earth I have set under foot: Zeus, keep Olympus yourself!'